Perennially clogged streets during the monsoons in Mumbai, the ongoing garbage crisis in Bangalore or the recent collapse of an under-construction building in Chennai are all telling signs that our cities are far from delivering a high quality of life to their citizens. Such crises often hog public memory, but for only as long as it is ‘fresh’. It is time now to scratch the surface and address the underlying factors that contribute towards making our cities unlivable.

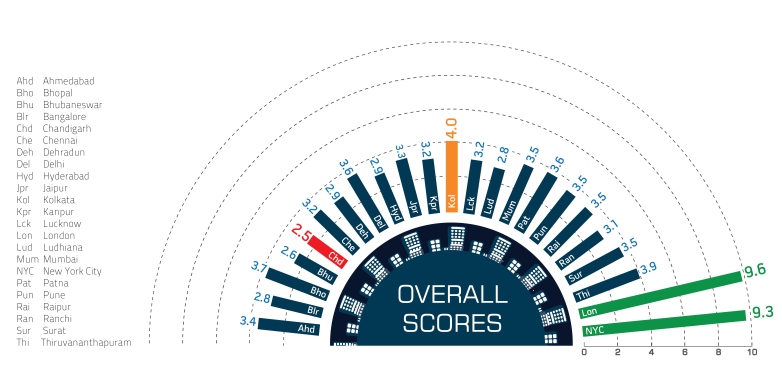

A study undertaken by the Janaagraha Centre for Citizenship and Democracy, a Bangalore-based urban advocacy organisation benchmarked 21 Indian cities against two global benchmarks on the basis of laws, policies, institutions, processes and accountability mechanisms that make up the systemic foundations of cities. Called the Annual Survey of India’s City-Systems, the study was carried out over a period of six months and finds that average Indian cities score in a range of 2.5 to 4.0 on 10 in sharp contrast to the global benchmarks of London and New York which score 9.6 and 9.3 on 10 respectively.

Pic: ASICS report

Why do city-systems matter?

The abysmal findings are a matter of concern as India, like most countries around the globe, is urbanising at a very fast pace. The World Urbanization Prospects - 2014 Revision, released by UN-DESA earlier in July, shows that 54 per cent of the world’s population lives in urban areas in 2014. The galloping urbanisation is also evident from the fact that 30 per cent of the world’s population was urban in 1950 and the same is projected to increase to 66 per cent of the world’s population by 2050.

India is projected to add 404 million urban dwellers between 2014 and 2050. Along with China and Nigeria, it will account for 37 per cent of the projected growth in the world’s urban population in that period.

“As the world continues to urbanize, sustainable development challenges will be increasingly concentrated in cities, particularly in the lower-middle-income countries where the pace of urbanization is fastest. Integrated policies to improve the lives of both urban and rural dwellers are needed,” states the UN-DESA report. “Governments must implement policies to ensure that the benefits of urban growth are shared equitably and sustainably,” it adds.

While the projections could be debated, the need for sustainable urban development remains undisputed. The current approach to urbanisation is however, piecemeal and haphazard. Routine flooding in Mumbai or the garbage crisis in Bangalore have traditionally been dealt with by quick fixes such as setting up of enquiry committees or suspension of officials, with no real effort towards examining the root of the problems - whether it is the ageing drainage network or unscientific landfills.

A new government taking over at the Centre in India presents an opportune moment to initiate dialogue on a systemic approach to urban transformation.

A diagnosis of India’s cities

The Annual Survey of India’s City-Systems evaluated 21 Indian cities, spread across 18 states on four crucial city-systems components: urban planning and design, urban capacities and resources, empowered and legitimate political representation, and transparency, accountability and participation.

Average scores of Indian cities on these categories are 2.2, 2.6, 4.9 and 3.3 respectively highlighting that much remains to be done towards sustainable urban transformation.

Indian cities score 2.2 on 10 on an average on urban planning and design indicating that our cities are built on a flawed systemic framework. When viewed from a systemic perspective, even the planned city of Chandigarh scores 0.6 on 10, the lowest among the 21 cities analysed, as it is has failed to legislate a contemporary Town Planning Act of its own or prepare metropolitan and ward-level plans.

No city with the exception of Delhi truly devolves planning to the neighbourhood level, as recommended by the 74th Constitutional Amendment Act, 1992. While 16 of the 21 cities have passed the Community Participation Law, no city except Hyderabad has constituted Area Sabhas to involve citizens in policy-making at the neighbourhood level. City governments are hesitant to disclose their inner workings.

The study further finds that 15 of the 21 cities were covered by the Public Disclosure Law (PDL), but only eight have bothered notifying rules. Larger cities including Delhi, Kolkata and Ahmedabad are till date not covered by any such legislation.

Of the 21 cities, only Delhi, Mumbai and Surat disclose their internal audits to citizens and none of the 21 discloses its audited annual accounts. All these factors create a lack of trust among citizens towards their governance that is further compounded by the lack of transparency, accountability and participation in our cities.

The spatial development planning of India’s cities is also stuck in a time warp. Planning is still being determined by archaic legislations which don’t reflect contemporary realities with cities like Hyderabad depending on Planning Acts as old as 1920. None of the 21 cities for instance, use a digital map for planning across its sectors. Even Jaipur which proactively conceived a digital base map through private players in 2007, fails to use it, in practice.

Building violations routinely flourish in the wake of planning acts which lack teeth and spatial development plans which lack implementation. The unfortunate outcome of this is all too familiar-instances like the recent building collapse in Chennai which claimed 61 lives repeating themselves across cities. The study finds that all 21 cities analysed uniformly score a zero when it comes to implementing their master plans, an area where London and New York score a perfect 10.

The bleak diagnosis is reflected in the component on urban capacities and resources as well. The study shows that no city scores more than 5.0 on 10 owing mainly to weak powers of taxation at the city-level, lack of self-sufficiency in revenues and inadequate and poorly trained staff.

Unlike London and New York where Mayors display strong leadership, many Indian cities lack systems that allow for empowered and legitimate political representation. Interestingly, it is relatively smaller cities like Bhopal, Chennai, Dehradun, Jaipur, Kanpur, Lucknow, Raipur and Ranchi which have directly elected Mayors with a five year term.

Larger cities continue to have Mayors who are indirectly elected for tenures as short as one year in Delhi, Bangalore and Chandigarh or 2.5 years in Ahmedabad, Mumbai and Surat, making the key leadership position potentially ineffective.

It is important to note that neither of the city-system components is mutually exclusive and a synchronous approach to fixing cities is crucial. Take for example, a directly elected Mayor. The true effectiveness of a Mayor will depend on the powers that are devolved to him/her and the city council as well as the institutional capacities of the urban local body.

In the eight cities (Bhopal, Chennai, Dehradun, Jaipur, Kanpur, Lucknow, Raipur and Ranchi) which have directly elected Mayors with a five year term, the councils are vested with very limited powers, performing as few as three of the 10 critical civic functions, Janaagraha analysed. Their average per capita expenditure on capital infrastructure is only around Rs 1,400 as compared to the Rs 2,200 or more of average Indian cities. A Mayor without subsequent institutional backing or resources is then potentially ineffective.

The way forward

The benchmarking exercise undertaken provides a starting point for city governments to introspect on their systemic shortfalls and holds out valuable peer learnings from cities, both within India and overseas. The initiatives demonstrate in effect how political will can be translated into systemic measures that contribute towards building sustainable cities.

To improve its planning outcomes for instance, city administrators might want to turn to New York’s PlaNYC initiative, which provided a sustainability and resiliency blueprint for New York City in 2007. Anchored by the Mayor’s office, the initiative brought together 25 city agencies and others in academia, civil society, business and community leaders to pre-define long-term planning goals. It has since been publicly disclosing the delivery of targets.

Some Indian cities too have participatory mechanisms worth mention. Pune for instance, has instituted an annual participatory budgeting process which allows citizens an opportunity to chalk out their priorities for the city budget. Surat publishes weekly data on budgeted and annual expenditure thereby allowing citizens to track where their money is going.

Such initiatives hold out promise of change. It would be prudent for other city administrators to go back to the drawing board to examine the systemic foundations of their cities and initiate reforms in a manner that ensure sustainable and equitable urban transformation.