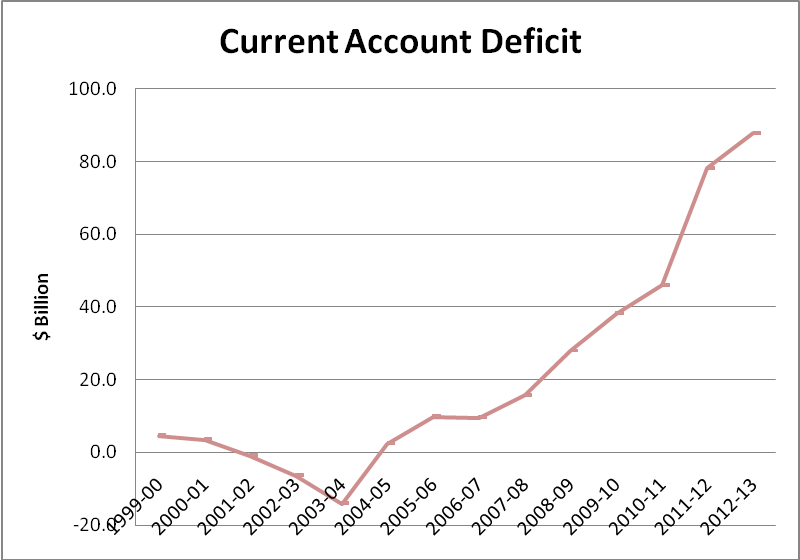

India had a deficit on its current account of nearly $90 billion in the year 2012-13. The current account is a record of transactions relating to exports, imports and cross border income transfers for a given period, that is, transactions that require a foreign currency. A deficit on the current account (CAD, in short) means that India has to pay out more than it receives on these transactions. The deficit can be bridged either using the country’s foreign exchange reserves or from foreign capital inflows.

The enormity of last year’s deficit can be seen from the fact that it exceeds the value of exports of theentire computer software and service industry.

Figure 1

In recent years, the current account shows an interesting variation, with a sharp inflection in 2004-05. India actually had a surplus on its current account - foreign exchange to spare - for some years, until a sharp reversal occurred in 2004-05. Since then, the current account deficit (CAD) has increased at a very rapid rate.

The CAD has generally been balanced by the inflow of foreign capital coming in a variety of forms - direct investments, portfolio investments, corporate loans and deposits of non-resident Indians. Unsurprisingly, capital flows have been determined not only by the opportunities available in India for profit, but also the global economic environment.

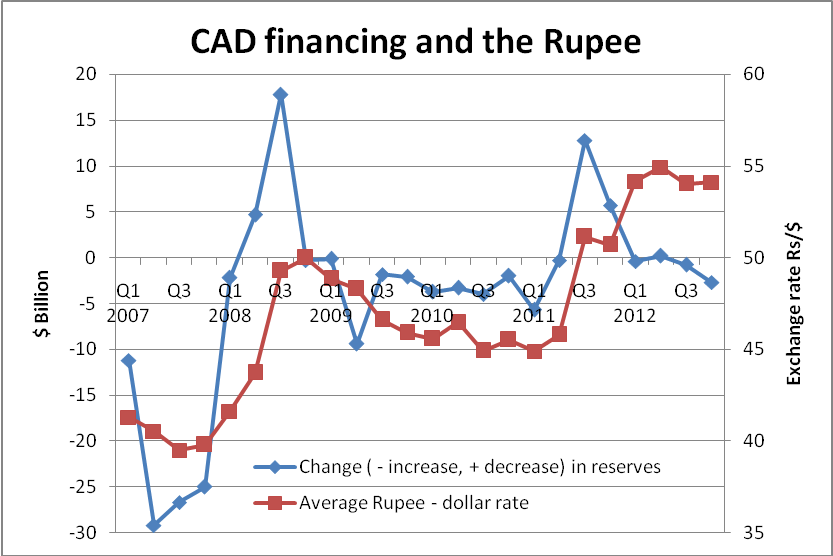

In the years before the 2008 global financial crisis, capital inflows comfortably covered the deficit and added to India’s foreign exchange reserves. The situation changed dramatically in 2008-09 with capital inflows falling short of a sharply rising CAD. India had to draw on its foreign exchange reserves to finance imports that year. In the following years, capital inflows have been just about keeping pace with the increasing CAD, except over some quarters of 2011 when there was again a shortfall with a draw-down on the reserves.

Figure 2 shows the quarterly changes in foreign exchange reservesafter accounting for the current account deficit and net capital inflows (blue line, left vertical axis) for the last five years.A decrease in the reserves implies that capital inflows were not sufficient to balance the CAD in that quarter.

Figure 2

There are immediate and longer term negative consequences for the economy arising out of dependence on capital inflows to finance a large part of the imports.

One long term consequence with a bearing on the CAD is that with the increasing debt component of foreign capital in India (now exceeding 52 per cent), interest payouts have also increased adding to the deficit. In 2012-13, net investment income transfers constituted over 25 per cent of the CAD.

Among the immediate consequences are the volatility and rapid depreciation of the rupee. Figure 2also displays the quarterly average rupee-dollar exchange rate for the last five years (red line, right vertical axis).

Periods when capital inflow is inadequate to finance imports, leading to a net depletion of foreign exchange reserves, see sharp depreciation in the value of the rupee. Two such recent periods were seen from Q3 2007 to Q4 2008 when the rupee depreciated by 27 per cent and then from Q1 2011 to Q2 2012 when the fall was 22 per cent.

That the value of the rupee is acutely dependent on the delicate balance of the CAD with capital inflows is only one part of the problem. A large part of the capital inflow - nearly 25 per cent of foreign capital in India as of March 2013 - is portfolio investment, which is money that can be withdrawn very quickly when investors perceive better opportunities elsewhere. In a recent episode, the rupee depreciated by over 13 per cent in the eight weeks up to 7 July 2013, exceeding Rs 61 to the dollar, after foreign portfolio investors started withdrawing capital from India on indications of higher interest rates in the US.

The government’s economic managers, who swear by the dictum that the “market knows best”, do not find anycall for intervention. They preach that rupee depreciation may actually be a blessing as it will spur exports by making them more competitive.

For the average citizen, however, the sharp rupee depreciation imposes severe hardships by making essentials such as energy, fertilizer and edible oil more expensive, thus fuelling inflation across the board.

Roots of the Deficit

So why is the CADgrowing so rapidly?

There are five items that constitute the overwhelming part of India’s current account. These are merchandise exports, software exports, remittances (by Indians working abroad), all of which earn foreign exchange for the country, and merchandise imports and net investment income payoutswhich involve foreign exchange outflow. The excess of merchandise imports over exports constitutes the merchandise trade deficit.

Figure 3

In the period up to 2003-04, exports and imports followed a similar rising trajectory. Though there was a deficit in merchandise trade, software exports and remittances from Indian workers - essentially a form of export of labour services - compensated for it, leaving an overall surplus on the current account.

2004-05 onwards, even robust growth in software exports has been unable to compensate for the rapidly climbing merchandise trade deficit.

Imports have been growing at a compounded annual average growth rate (CAGR) that is 4 per cent higher than that of exportsover the same period. This is the cause of India’s burgeoning current account deficit.Clearly, this is not a problem that has arisen overnight, but has been building up for nearly a decade.

Import growth - a closer look

Why have imports grown so rapidly in value - at a CAGR greater than 22 per cent - from 2004-05? There are several causes for this.

One is the steep rise in the global price of commodities such as crude oil and gas, gold, coal, metal ores and scrap which India imports. Commodity prices have also affected the prices of manufactures that use them as inputs, such as fertilizers and synthetic rubber, which again are on India’s import list.

The import bill has also gone up because of greater imports of commodities, intermediate goods and capital goods for meeting the needs of increasing exports and higher consumption in India. Production of natural and synthetic rubber has, for example,has more or less stagnated in India, requiring increasing synthetic rubber imports to enable the increasingproduction of tires for local consumption and export. In the case of fertilizers and petroleum gas, there has been a rapid increase in consumption. In capital goods, there have been huge cumulative imports of items in categories such as ships and floating vessels, aircraft and parts and power plant equipment.

However, that is not all. Consumer product imports - imported whole or in parts to be assembled - have risen sharply. The telecom revolution is almost entirely based on imports. So is the case with the spread of computers and consumer electronics. High end brands of products traditionally made in India â apparel, shoes, cookware, etc - are being imported.

The government, on its part, has actively encouraged imports through policy measures. Import duties have been progressively reduced across the board. According to Planning Commission data, the weighted average import duties for capital goods fell from 20.7 per cent in 2003-04 to 5.6 per cent in 2009-10 and for intermediate goods from 23.6 per cent to 6.8 per cent. Most remarkably, the duties on consumer goods were brought down from 51.8 per cent in 2003-04 to 42.9 per cent in 2004-05 and progressively down to 12.5 per cent by 2009-10. Customs duty across the entire range of mobile phones is now only 1 per cent.

Gold has also been favoured with official largess. The duty rate on gold bars was slashed in 2002-03 and kept ridiculously low - in the region of 1to 2.5 per cent - till early 2012. Preferential treatment under FEMA regulations ensured smooth and uninterrupted supply of imported gold. Investment in gold was made easy by authorizing retail salesof bars and coins by banks, trading in commodity exchanges with the possibility of taking physical deliveries and through gold ETF’s (that were accorded the same tax treatment as debt mutual funds, even though the gold with these ETF’s served no productive purpose). In 2002-03, gold already accounted for 6.3 per cent of India’s import bill. By 2012-13, gold imports had gone up eight times in value and constituted nearly 11 per cent of the import bill.

The public interest in restricting imports

The basic imbalance in merchandise export and import growth points to serious problems with Indian manufacture and the overall pattern of economic development in India. The underpinnings of the growth of the last decade need to be carefully examined. There are serious concerns about the excessive import dependence of many sections of Indian industry and lack of its export competitiveness in all but a few areas. These are questions that the government’s economic advisors really need to dwell on.

If the CAD is to be tackled head on, there can only be two ways: increase exports or reduce imports. Increasing exports would take time, even if the government had some new ideas on how to go about it. It seems obvious that the immediate efforts should,therefore, centre on curbing imports.

Gold stands out as the prime candidate, constituting nearly 11 per cent of the import bill, as mentioned earlier. According to different assessments (World Gold Council - an association of gold miners and the All India Gems and Jewellery Federation - the main association of jewellers in India), an entire one-third of the gold imported is sold in the form of bars and coins to investors, with the rest going into jewellery (part of which is exported). Investment in gold (which has to be paid in dollars) can be looked upon as a form of ‘capital flight’ out of the country. Wealthy Indians have parked in the range of Rs1 lakh crore in gold in just the last year obviously to hedge against inflation and rupee depreciation.A clamp down on investment in gold would be fully justified.

Cutting down gold imports is not the only option. Last year, $5 billion worth of gold jewellery was imported into India, a country that specializes in making gold jewellery! Imports of mobile phones over the last 3 years averaged $5 billion annually, with even the most expensive mobile phones attracting only 1 per cent duty. India has thrown open its gates to every variety of high- end foreign goods and there are pockets here which can afford these. But if the choice lies between restricting access of a rich minority to high-end imported consumer goods and ensuring supply of essential commodities at stable prices to all, then surely public interest lies in the former.

So what is the government doing to bring down the CAD?

Shockingly, it seems next to nothing.

The Minister of State for Finance stated in a written reply to a question in Parliament in May 2013that “no target has been set for the CAD”. He talked of measures taken to “boost” exports and reduce imports of gold and diesel.The measures for export are in the nature of increased subsidies to exporters and more relaxed norms for setting up SEZs. The import control measures, according to the Minister, are higher customs duty on gold and higher administered prices for diesel.The government’s economic advisors cannot be unaware that both gold and diesel imports have proved to be price-inelastic!

The Government has no real plans to correct the merchandise trade imbalance that is at the root of the current account deficit.Surprisingly, there is almost a conspiracy of silence on this issue. Neither mainstream media nor major political parties have questioned the government on itsstance on trade.

The Government’sfocus instead is entirely on “financing” the CAD by attracting more foreign investment. It spends all its energies in floating new external borrowing schemes or tinkering with existing regulations governing foreign investment.

Leaving aside fortuitous circumstances - a sustained fall in global commodity prices, perhaps, or a steady rise in ‘investor sentiment’ - India’s citizens are in for many more bouts of imported inflation.