Indian Environment Minister Prakash Javadekar recently described the much-talked about climate deal negotiated between the USA and China as one that was “not so ambitious”. He is reported to have told mediapersons that "Whatever intentions have been declared by the US and China is a good beginning, but it is not as ambitious as people wanted it to be."

This comment naturally leads to questions over what an ambitious climate deal would look like in Paris in 2015, and the role India that will be willing to play in such a deal to keep the rise in global temperatures below 2 degrees Celsius.

The BASIC (Brazil, South Africa, China and India) countries have mostly stuck to common positions on climate change in UNFCCC negotiations, on issues such as equity and common-but-differentiated-responsibilities (CBDR).

Given this G2 deal, it will be interesting to see how this is going to unfold within the BASIC group, as China has taken a stand that defies the strongly contested red lines of other BASIC countries, particularly India.

What is a big deal?

The climate deal between the US and China intends to achieve an economy-wide target of reducing US emissions by 26 -28 per cent below its 2005 level in 2025; China, on its part, intends to achieve its peak of CO2 emissions around 2030, and to make best efforts to peak early. To facilitate this, the latter also intends to increase the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to around 20 per cent by 2030.

As many have noted, this deal in itself will not be sufficient to cut global emissions, and it might also run into trouble given that the US Congress is now controlled by the Republican Party. The Republican leadership sees this deal as ‘unrealistic’ and a part of the President’s ‘war on coal,’ which would lead to a loss of jobs in the US.

Detractors also claim that the deal requires China to do nothing at all for 16 years. The Chinese commitment is not to any specific value of peak emissions, but rather a commitment that the country’s emissions will peak by 2030, and thereafter will not increase. The deal does not specify whether and by how much emissions will decrease after 2030.

The total US carbon emissions appear to have peaked already in 2005, despite its economic growth. Meanwhile, China’s new renewable power capacity surpassed its new fossil and nuclear capacity for the first time. All renewables accounted for more than 20 per cent of China’s electricity generation and its total investment in renewable energy sector for 2013 was approximately $56.3 billion.

The recent deal and domestic actions in China serve to show that it is committed to reduce the growth in emissions by 2030. However, one can always argue whether this is too little or too late to keep the temperature rise below 2 degrees Celsius.

With the EU already committed to a 40 per cent reduction below 1990 levels by 2030, and now with the US and China also joining the ranks, the spotlight will focus squarely on India. The question being asked is whether India will rise to the occasion and take on concrete commitments or not.

The refusal to move on

The official Indian position on climate change was initially formed in the 1980s and 90s, heavily influenced by a report titled “Global Warming in an Unequal World” by Anil Agrawal and Sunita Narain. This report argued for allocating equal access to the atmosphere for all individuals in the world, the per-capita allocation principle.

India was even successful in getting the terms “historical emissions” and “common but differentiated responsibilities” (CBDR) inserted as guiding principles in UNFCCC negotiations.

Even decades later, the Indian government holds the very same principles sacred and argues that:

- Developed countries and historical emissions are responsible for climate change.

- India’s very low per-capita carbon emission exempts it from taking any binding commitments.

- India requires rapid economic growth to alleviate poverty and provide energy access.

- India is very vulnerable to climate change impact and hence, requires financial, technological, and capacity-building support from developed countries.

Even with the change of government and governing philosophy, the climate position has not changed much. In a recent interview with The New York Times, Javadekar argued that, “Twenty per cent of our population doesn’t have access to electricity, and that’s our top priority. We will grow faster, and our emissions will rise.” He also said that improving the living standards of India’s 1.2 billion people would require building new coal-powered electricity and transportation.

India has emphasised that the elements of the 2015 agreement should give effect to the principles of equity and CBDR---a position etched in the 1990s.

Misplaced priorities

At a recent conference in New Delhi, India’s power minister, Piyush Goyal is reported to have stated, “India’s development imperatives cannot be sacrificed at the altar of potential climate changes many years in the future. The West will have to recognize we have the needs of the poor.”

To meet the challenges of poverty, Goyal promised to double India’s use of domestic coal from 565 million tons last year to more than a billion tons by 2019. The government has signalled that it may denationalise commercial coal mining to accelerate extraction. All this coal will apparently be used to lift Indians out of poverty and provide them access to energy, and therefore India remains hesitant to commit itself to carbon emission reduction. However, this argument calls for deeper analysis.

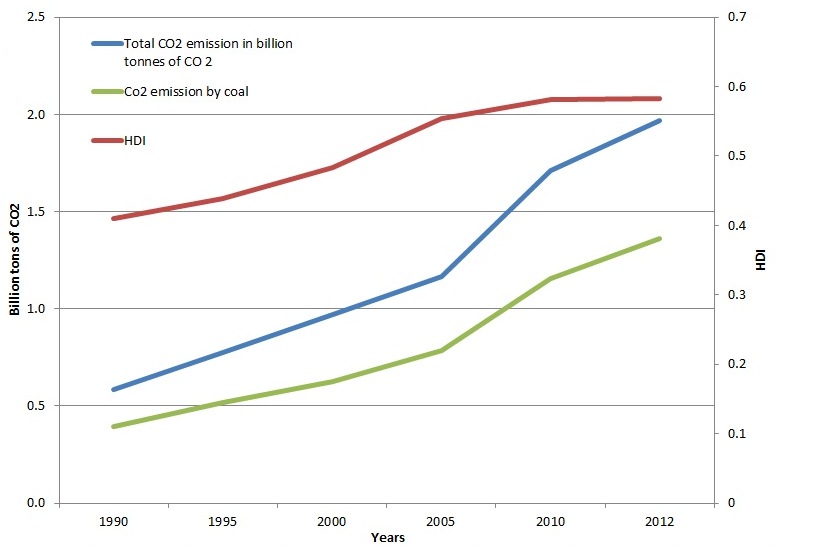

The emphasis of the Indian government on uplift of its millions from poverty is legitimate; however, the overemphasis on linking poverty reduction to increased carbon emission and building more coal power plants is not correct. A very straightforward analysis of carbon emissions versus Human Development Index (HDI) shows that the increase in carbon emissions over the years has not resulted in increased poverty alleviation.

The addition of more coal power plants on the pretext of meeting the needs of the poor has not resulted in greater energy (electricity access) access, and approximately 400 million Indians continue to not have access to modern energy.

Data Sources: Total CO2 emissions data-The World Bank | Coal emission data-International Energy Agency | HDI- UNDP (Human Development Report)

The graph above shows that human development indicators such as income, energy consumption and health, flat-line and do not directly correlate with increased emissions.

Therefore, the Indian government’s logic behind not agreeing to take on any commitments is misguided. There can be political or economic reasons for not doing so, but it should not be done in the name of poor Indians.

Climate Action and Development: Two sides of the same coin

One of the driving forces behind China’s decision to ink a deal with the US on climate change has to do with the alarming levels of pollution in China, and its impact on its economy and citizenry. Even India is in a similar situation, where pollution from burning coal and emissions from transportation has choked many cities and small towns.

Unchecked pollution and carbon emission are taking an economic toll on India as well. A World Bank report on India finds that the combined cost of outdoor and indoor air pollution is more than $40 billion annually, or more than three per cent of India’s 2009 GDP.

|

Sector policy case studies: Monetized health, agricultural, and energy benefits in 2030 |

|||

|

Regions |

Health |

Agriculture |

Energy Saving |

|

India |

$293 billion |

$14 billion |

$75 billion |

|

China |

$66 billion |

$69 billion |

$ 311 billion |

|

US |

$ 8 billion |

$46 billion |

$ 188 billion |

Source: World Bank

When other environmental degradation is factored in, including crop, water, pasture, and forest damage, the total is closer to 5.7 percent of India’s GDP. This pollution most strongly affects the poorest members of society.

There is growing evidence that “climate-smart” development is achievable, and it counters the fear that climate action would lead to loss in jobs, hamper growth, and competitiveness. The World Bank suggests that climate smart investments and efforts can advance urgent development priorities while, at the same time, addressing the challenges of a rapidly warming world.

For example, if India built 1,000 kilometers of new bus rapid transit lanes in about twenty large cities, the benefits over 20 years would include more than 27,000 lives saved from reduced accidents and air pollution, and 128,000 long-term jobs created. It would also have large, positive effects on India’s GDP, its agriculture, and the global climate.

The above table shows that India has much more to gain by moving to climate-smart development rather than continuing on the “business as usual” path, with its over reliance on coal in the energy sector.

The right choice

India will have to make choices going forward in the climate negotiations. One route would be to stick to its usual approach of differentiation of Annex I and Annex II countries, play the poverty card, and refuse to take any binding cuts.

Another approach could be to take bold action, and not shy away from building upon the climate measures already taken, in terms of scaling up solar energy, setting up a 100-crore climate adaptation fund and its earlier commitment to reduce emissions by 20 to 25 percent from the 2005 levels by the year 2020.

Rather than hiding its achievements in climate action, India should proudly own them and make it more ambitious. Focusing solely on historical responsibility is not pragmatic strategy. Given India’s climate vulnerability, the Modi government should be pushing the US and China to take on stronger commitments while also committing India to more ambitious emission reduction goals. This will allow India to play a constructive role in the international climate change negotiations in Paris 2015.