Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai is a documentary directed by Nakul Singh Sawhney. It is a part of the screening programme by Cinema of Resistance translated as Pratirodh Ka Cinema in Hindi, a people's resistance movement through cinema – against the neo-liberal economic onslaught, the feudal fetters, the imperialist domination and that of patriarchy, caste-oppression and communalism. This has become a countrywide movement where the screening is as or perhaps more important than making such films. This is underscored by the fact that the volunteers and activists of Cinema of Resistance across the country have collaborated on widespread screenings of the film without any financial or organizational backing or NGO funding or any kind of assistance.

On August 1 this year, members of the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad forcefully stopped the screening of the documentary at Delhi’s Kirori Mal College. Not to be swayed by this disruption, in a unique display of solidarity, Cinema of Resistance organized countrywide screenings in at least 60 different venues across fifty cities on August 25 as a mark of protest against attempts by Hindutva groups to halt its screening at the University of Delhi and later at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU).

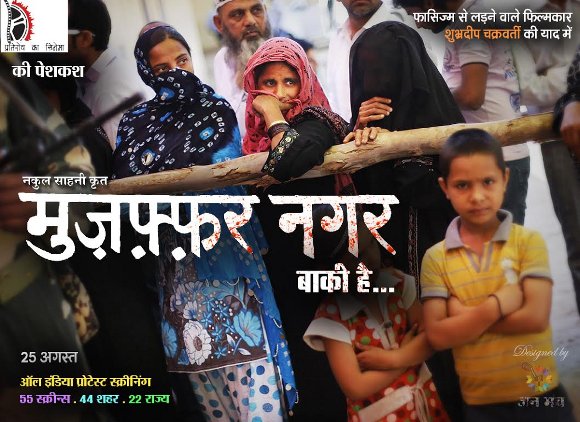

A poster of Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai. Poster design: Janmanch Faizabad, Pic: Cinema Of Resistance, Kolkata chapter

The organisers sent the DVD of the film free of cost to those who wanted to screen the film on August 25. Most places successfully screened the film while in some places such as at Santiniketan in Bolpur, screening was stopped by the local police after 40 minutes. The screening at Mumbai's The Hive was cancelled after police intervention. At Space in Chennai, police stopped the screening but a major slice of the audience along with the organizers rushed to the Max Mueller Bhavan to immediately organize a private screening.

Sawhney is reportedly overwhelmed by the response of the people who have fearlessly stood up against the attempt of the government and the ruling party to silence the voice of dissent. Considering that more than 7000 people watched the documentary on a single day, he agreed that in a way the obstruction provided them an opportunity to reach out to the larger audience and spreading the message through his film.

The documentary

Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai narrates the true story through live footage of the aftermath of the riots that took place in Muzafffarnagar and Shamli districts in western Uttar Pradesh in September 2013. The film shows how a district fondly called Muhabbatnagar by its residents and neighbouring districts because of the undisturbed harmony between Hindus and Muslims turned into a veritable “Nafratnagar” if one could sadly call it that because the film shows how a place of love has been reduced to a place of death and destruction.

The film opens on the hands of a little girl drawing matchbox-stick sketches of her father, their house in a sketchbook, drawing neat lines across with a ruler as she talks about what she is drawing. She explains that the man with raised hands is her father who tried to stop the invaders from entering their home and was struck down by a bullet. “Who were they?” asks the voice-over and she says, “the attackers were from our neighbourhood” afraid of mentioning any names.

This film is an independent documentary that slowly, layer by layer, unfolds the conspiracy of political parties which actually triggered, by deliberate design, communal massacres in a district that had never known communal conflict of any kind before. The aim of these political parties was to grab power through votes gained with the help of capitalist and feudal forces of the region during August-September 2013.

The documentary assumes significance because it traces the roots of the politics that led to the turmoil through flashbacks recounted by the victims and their families.

The film is structured mainly through interviews with the survivors, family members of victims, dishoused and displaced men, women and children who are practically living off sugarcane at the temporary camps waiting for compensation. It reaffirms what many consider to be the most heinous act of anti-Muslim pogrom since the Indian Independence. More than 100 people perished and nearly 80,000 people were displaced in these two districts, which incidentally have been known for their communal harmony!

A still from Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai. Pic: Cinema Of Resistance, Kolkata chapter

The film, in an attempt to trace the root of this sudden violence, oscillates between various socio-political-economic nuances in the zones affected by the violence.

Director Sawhney and his team move through the affected areas, travelling along the earthy roads framed by thinned trees with skeletal branches while the voice-over explains in neutral tones how and why these were the worst riots since Independence.

Sawhney tries to give voices to all people involved in the story – the perpetrators, mainly from Hindu right wing political parties preparing for the elections in a state where they had not won since 1984; the observers, both Hindu and Muslim who give vent to their feelings and voice the common grouse that the riots and the killings are designed by politicians, their goons, their musclemen, their stooges and their electoral candidates mainly from the majority community.

The survivors’ voices break as they go back into the recent past. The heavily lined face of an old woman laments that the mansion in which she lived that had 52 doors and was large enough for one to get lost. The camera returns to the debris of this mansion twice or thrice and at one point, one can hear the fading voice of Salim Mirza’s dying mother in Garm Hawa (1973), who wished to be brought back to their old haveli one last time before she died.

For those not familiar with the reference, Garm Hawa, directed by M S Sathyu on a script penned jointly by Kaifi Azmi and Shama Zaidi, was based on an unpublished short story by Ismat Chughtai. This film is significant as a frame of reference because it is set against the backdrop of Agra also in Uttar Pradesh where Indian Muslims, specially after the Partition of India in 1947 and the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi in 1948, were forced to migrate to Pakistan though they had lived in India all their lives and many were even born here.

The film focuses on Salim Mirza (Balraj Sahni), a businessman who hates to leave even when his older brother and his family choose to go to Pakistan. This film was a milestone because for the first time, an Indian film tackled the tragedy of Muslims in India after the Partition without exaggeration or melodrama, with quiet assertion offering a humane document. However, the reference will be lost on those who have not seen nor heard of Garm Hawa.

Does this mean that the situation has worsened for Muslims sixty six years after the Independence? Why? It is the camera that provides the answers as it wanders across the remains of three different three-wheelers owned by a successful young businessman now fallen on bad days. Is he the Salim Mirza of 2013? A young man makes a valid statement. “Why do you ask who died – Hindu or Muslim? Human beings died and that is important. The ones who died were weak, vulnerable, helpless and poor. Not a single politically, financially and communally powerful person seems to have been affected.”

When the voice-over asks a group of men how could they possibly come back to their towns after the riots were over, they laugh and say they had to come because they had their lands and their farms and their businesses here, certain that the perpetrators would not touch them for the financial power they have.

When a group of young girls, both Muslim and Hindu are asked whether they were molested or teased by boys of a given community, they all say the obvious – it does not matter what community the boys belong to, because molesting and eve-teasing are independent of communal identities. “Why should girls be forced to be the stakeholders of the family’s izzat? Why not men?” asks one, as she smiles into the camera.

A still from Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai. Pic: Cinema Of Resistance, Kolkata chapter

The roads are deserted, the homes are in shambles, machines are broken or burnt and a gas cylinder rolls on the road reminding us that it once took pride of place in some one’s kitchen that once was. All this is in the wake of a young Muslim boy having been brutally killed and his body left on an open street because allegedly he raped a Hindu girl. In retaliation, the two Hindu boys who had reportedly killed the Muslim boy were also killed. When the camera closes in on a film clip of two bodies curled in death, the voice-over says that this clip is from an incident that happened in Pakistan two years ago!

The only problem with the film is its inordinate length that runs into 136 minutes of screening time with repeat shots and repeat interviews that could have done with some sharp editing. One could see a part of the audience walking away from Muktangan theatre in Kolkata because it was getting late. The layman in the audience might have felt that the same things were being said again and again.

Sawhney has not tried to compromise on the content by harping on the aesthetics of film making. The empty roads deserted of people, small children wandering aimlessly not knowing what to do, women gathered together not knowing what to expect next, the fireworks symbolising the change of guard at the centre and also in Uttar Pradesh at the same time, did not really need much repetition.

Sawhney tries to maintain an objective and neutral stance as much as the situation permits him to, but the facts come across during the pre-election hate speeches filled with communal colours more from the majority and some from the minority as well. The camera returns to an old man who was once the headmaster of a school in the neighbourhood whose name no one remembers because everyone calls him “Master” and respects him a lot. He sadly says that this attack on their community was something he had never witnessed before.

The film focuses subtly but strongly on children who are the worst victims. No going to school for them. One sees the bandaged foot of a small child standing near a ditch. Another small boy lies down in the ditch again and again. The ditch for these innocent little kids symbolises a grave and since they have nothing better to do, they play lying down in it and coming out again and again. A father laments that his little boy is so shell-shocked by the riots that he keeps repeating the same sentence again and again.

The sometimes quiet and sometimes vocal resistance of those, who want to come back but cannot because they have no homes to come back to shows they’re longing to return to their original homes. Have they given up? Maybe some have but most have not because hope still rages in their minds that sometime in the future, their lives will become better. Maybe more such historic screenings might change the mindset of the people of this country. Maybe……