Over the years, many anti-graft activists have been murdered or assaulted upon exposing corruption based on findings from Right To Information (RTI) applications made by them. In 2012, M Lingaraju (40) was hacked to death in Bangalore, after he exposed illegal assets acquired by a city corporator. In 2010, Gujarat-based activist Amit Jethwa (33) was shot dead after he filed court cases about illegal mining in Gir Forest. These are only two names in a long list of victims.

Activist groups have repeatedly demanded government action in such cases, and also police protection for those under threat. But little has changed and the protagonists continue to live in fear. However, a ruling by the Calcutta High Court last November, brings some hope as it assures better confidentiality for RTI applicants.

The order says that applicants need not mention their full address in applications; instead they can simply mention their post box number. The court had ordered the central government’s Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions to circulate a copy of the order among all concerned.

On 8 January, the Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT) under the Ministry, issued a memorandum about the court order to all state and central government ministries and organisations. Backed by this, an applicant can now file an application using only his name, post box number, post office name and PIN code. Government departments can insist on full address, only if they have any difficulty with the post box number. In the order, the court had also said that government agencies should not reveal applicants’ details, especially on their websites.

The ruling

The order came on the back of a PIL filed by Avishek Goenka asking that authorities should not insist on full address of an applicant, when a post box number may effectively conceal his identity. Goenka is not an RTI activist; in fact, he describes himself as a PIL activist. He has earlier won court orders in many PILs, including those on removal of tinted glass from vehicle windows, mandatory address verification for prepaid mobile connections etc. Speaking to India Together, he says that activists may still get identified, but that this order may at least bring down the number of such cases.

Goenka had initially filed the PIL at the Supreme Court in 2012, praying that applications should be allowed to file RTIs using both post box number and email for the sake of safety of applicants. The SC had said that it could not give any directions on this, as law-and-order was a state subject. It also said that allowing applications through email could lead to misuse of RTI, as anybody would be able to send applications from anywhere. Goenka then submitted his petition to the Calcutta High Court, after removing the reference to emails.

The Bench of Acting Chief Justice Ashim Kumar Banerjee and Justice Debangsu Basak consequently passed the order, which, in effect, is only an explicit clarification on the existing law. Section 6(2) of the RTI Act, 2005, clearly says that applicants should not be asked to give any personal detail, except what is needed to contact them. The High Court said in its order that where the legislature was of the opinion that applicants did not have to disclose personal information, authorities should not insist on the same.

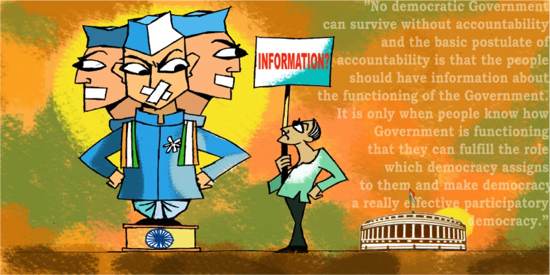

Pic: Farzana Cooper (India Together Files)

In mid-January, Goenka sent a petition to the Ministry of Personnel, requesting that RTI replies be sent to applicants via email. “If a person has given his address or post box number in the application, the authority can send their responses and documents to his email id. This would be quick and easy – the cost of photocopying and sending documents would also be cut,” says Goenka.

Mumbai-based RTI activist Krishnaraj Rao adds, “Section 6(2) was earlier open to interpretation, and authorities sometimes insisted on getting personal details of the applicant.” He says that there may be officers who are still unaware of the circular, but then activists can now educate them by showing them the circular or attaching it with their application.

How to get a post box

Any person or organisation can get a post box by paying a rent of Rs 150 per year or Rs 50 per quarter-year. Postboxes are similar to bank lockers and are located within post offices. They are only for receiving incoming mail. All correspondence except registered/insured/value payable articles will be delivered to the post box.

To get a post box, you can approach the post office that usually delivers mails to your address. Most delivery post offices (the ones which have a postman to deliver mails) have the facility. In case your local post office does not have the facility, you may be allotted a post box in another post office in the same town.

You should write an application to the Postmaster in the prescribed format, giving your business address; you should mention the nature of your business and get it certified by two respectable people not related to you. The Postmaster may not insist on certification if he already knows you well. You can use your post box during the business hours of the post office.

Where does it leave the whistle blower?

While it is true that courts have occasionally proactively dealt with cases of attacks on RTI activists and whistle blowers, the overall situation has not changed much. In some murder cases, courts have admitted suo motu petitions based on press reports.

In 2010, after the death of Pune-based RTI activist Satish Shetty, the Bombay High Court had directed the Maharashtra government to give police protection to RTI activists under threat, and also to ensure speedy investigation in cases of threat or attack.

But Rao says that there has only been lip service from the police. He says, “The Mumbai Police Commissioner did issue a circular to all police stations making it mandatory for them to register complaints from RTI activists. He also directed setting up of a committee comprised of some RTI activists and police officials at every police station. But nothing further was done.”

Rao says that, in fact, whistle blowers are being actively discouraged. “The Greater Mumbai Corporation now has a system by which only those who are personally aggrieved can file complaints on encroachments, unauthorised buildings etc,” he says.

Whistle blowers in governmental organisations have also been targeted in the past. Satyendra Kumar Dubey, who was killed in 2003 for exposing corruption in the Golden Quadrilateral highway construction project, and IOC officer Manjunath Shanmugam who was killed in 2005 for sealing petrol pumps selling adulterated fuel, are among them.

RTI activists had been pinning their hopes for some time on The Whistle Blowers Protection Bill, 2011, though they have also pointed out many problems with the Bill as passed by the Lok Sabha in December 2011. The Bill is pending Rajya Sabha approval now.

As per the Bill, the Central Vigilance Commission would be the authority for accepting complaints on central government agencies; State Vigilance Commissions can accepts complaint on state agencies. Complaints against MPs and MLAs can be filed with the Speaker/Chairman of the House.

Any individual, public servant or NGO can email or write to the authority, along with documents. However, one cannot send information anonymously or using false identity.

|

A Weak Bill

There has been a slew of criticism of The Whistle Blowers Protection Bill. For one, the private sector is entirely exempted from the Bill, even though it is not above corruption.

While The Bill specifies that complaints must be filed within seven years of the alleged act, the NCPRI (National Campaign for People’s Right to Information) – an organisation working to ensure proper implementation of the RTI Act – has said that there should be no time limit to file complaints and that the authority should complete all inquiries within 45 days. NCPRI has also demanded that the provision to dismiss ‘frivolous or vexatious’ complaints should be removed, since any complaint can be dismissed this way.

The Bill does not mention any penalty for victimization of the complainant either. The authority can only direct the organisation to take corrective action, and penalty is imposed only if this direction is not followed.

NCPRI says that there should be a detailed definition of victimization in the Bill. Venkatesh Nayak, member of NCPRI and CHRI (Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative), says that this is needed because a public servant may get sidelined at work or face disciplinary action as a consequence for raising an issue or complaint. “Higher authorities often mask retaliation as ‘routine administrative action’,” he says.

The Bill also does not allow for anonymous complaints. Rao says that such complaints should be accepted, since in practice, identity once disclosed cannot be kept confidential. “There seems to be an assumption that there is one person called the Vigilance Commission who will open envelopes directly, then keep it at home and take direct action himself. This never happens in an office; files move among different sections. Anyone in the office can leak out the person’s identity for a price,” he says.

Rao also points out that the Bill in its present form looks more like an anti-corruption Bill, and has been drafted without a clear idea of what whistle blowing actually is. “The focus of the Bill is on complaints filed against someone. But a person may simply want to complain about a wrong that has to be set right – for example, about adulterated street food - rather than complaining against a particular individual.”

Nayak says that Chief Ministers and the Prime Minister should also be covered under the Act. For complaints against employees of the judiciary - except High Court and Supreme Court judges – the Bill lays down that the High Court would be the competent authority. Moreover, as far as the procedure of inquiry is concerned, the Bill empowers the authority to start a discreet inquiry after confirming the complainant’s identity. The head of the government body (against which the complaint is filed) will then be asked to explain/submit a report.

According to Nayak, “The inquiry procedure in the Bill is not suitable for the judiciary though it has been covered under the Act. There is no ‘head of department’ in a court to respond to complaints against a judge. Also, where State Vigilance Commissions do not exist, the Bill allows the state government to designate any authority to take its place. But such an authority will be government-controlled.”

Amendments to dilute The Whistle Blowers Protection Bill

In August 2013, a set of amendments were proposed to the Bill, which, according to experts, will further dilute it.

One of the amendments seeks to prevent people from filing any complaint related to ongoing cabinet proceedings. This means that a potential whistle blower will not be able to attach to his complaint any Cabinet papers or records of deliberations of Ministers and bureaucrats as evidence. Only documents of cabinet proceedings that are obtained under the RTI Act can be attached with the complaint. However, under the RTI Act, such documents are not provided unless a final decision has already been taken on the proceedings.

While RTI activists have been trying to get this provision removed from the RTI Act itself, by this amendment, the provision will now be extended to the legislation around whistle blower protection as well. This will prevent the public from complaining against a potentially bad cabinet decision.

It has been specified that complaints that might incite an offence, or affect national security and integrity, foreign relations etc. will not be accepted at all. In practice, however, these definitions can be used arbitrarily to reject complaints.

The amendments also lay down that the authority should first check with an officer authorized by the state/central government to confirm that the complaint does not fall under these exempted categories. It can proceed only after getting the officer’s approval. Nayak says that this could well lead to complaints piling up as they await approval.

Moreover, according to the Bill passed by the Lok Sabha, public servants who file complaints will not be prosecuted under the Official Secrets Act, 1923. But the amendment removes this clause, making public servants who complain, vulnerable.

Activists claim that the proposed amendments to the Bill were notified stealthily last August and were not uploaded on any government website. The Lok Sabha will consider the amendments only once Rajya Sabha approves the current version of the Bill. After this, if the Lok Sabha approves the amendments without any change, the amendments will become applicable. However, if the Lok Sabha makes any changes in the amendments, these will have to be approved by the Rajya Sabha again.

It remains to be seen if the lawmakers will pay heed to RTI activists’ concerns on the issue. As of now, in all of this, the fate of the Indian whistle blower appears uncertain.