On 24 February 2010, the print daily Hindustan Times reported 50 chronic hunger-related deaths in Balangir district of Orissa. The lead story laid bare five deaths in the family of Jhintu Bariha in Gudighat village, Khaprakhol block of the district, which occurred between September 2009 and December 2009. India Together had earlier published my story on the same family (Starvation death continues as officials demur). There were also reports in the local language media on this issue.

The HT story ruffled the state and the national capital. One of the immediate upshots was the transfer of District Collector S Aswasti. Later, the cases were investigated by the special rapporteur of NHRC Damodar Sarangi; the High Court of Orissa also sought response from the state government.

Balangir district is part of the undivided Kalahandi-Balangir-Koraput (KBK) region of Orissa which is notorious for starvation deaths, child sale cases, overwhelming malnourishment, and acute poverty. About 62 percent of the 13.4 lakh people (Census 2001) in Balangir district live below the poverty line, official estimates suggest.

•

Starvation deaths continue as officials demur

•

Starvation persists in Orissa

The report of 50 deaths, ironically, evoked mixed response from social activists and the media. While some doubted the veracity of the number of deaths reported, others heaved a sigh of relief as this grave issue was finally being discussed at the national level.

Subsequently, I visited the district and interacted with some families who had lost their dear ones in the last two years. My primary focus was to ascertain the cause behind these tragedies and study the conditions under which these deaths occurred.

![]() Padmani, wife of Late Rahasa bhoi. Pic: Pradeep Baisakh.

Padmani, wife of Late Rahasa bhoi. Pic: Pradeep Baisakh.

1. Rahasa Bhoi, 45, belonging to ST community in Chhuinnara village, died in January 2009. He was a seasonal migrant worker for many years and used to migrate to Bangalore and Cuttack district of Orissa along with his family. In 2009, while the family was in Bangalore, he suffered from fever and severe headache. He was brought back to the village as the treatment he received in Bangalore did not help. His health deteriorated even after a one-and-a-half month stay at the Patnagarh government hospital. His case was referred to the Burla hospital -- one of the best government hospitals in the state. By then the family had spent Rs 60,000 on his treatment by selling its two acres of land, gold, etc. A chronically ill Rahasa Bhoi died. At the time of his death, he was unable to lift his head, move his legs and hands, or speak. The doctor could not tell what the disease was, says Brindavan Bhoi, nephew of Rahasa who used to attend on him at the hospital. Rahasa is survived by wife Padmani Bhoi, four daughters, and a minor son.

Following the tragedy and loss of assets, the family has slipped into the zone of high vulnerability. The local panchayat has given an APL card recently. A road work which began in November 2009 under Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) came to a halt as the villagers could not continue to work due to a three-month delay in payment. Dogged by lack of employment, three of Rahasas daughters are now migrating to Cuttack district to work in brick kilns while his wife does some work in the village whenever available. The eldest and the only married daughter Sumitra says, We used to get regular food only when we were at work in Bangalore as the landlord used to give us kharchi (weekly expenditure). But when we are in the village during off-seasons, there isnt much work available. We get to eat only when we get work; otherwise we almost go hungry. After my fathers death, the food intake of our family is worse than ever before.

When asked how she get her three daughters married, Rahasas wife had no answers.

2. Nidhi Biswal, 50, who lived in Tara village of Kapani GP in Belpara block, had a small patch of low-yielding agricultural land. The family used to migrate to Hyderabad to eke out a living. While at home, they used to depend on the rarely available work. In 2006, while in Orissa, Nidhi fell ill to diabetes and sickle-cell disease and consulted a private clinic at Belpada. His wife Bhumis efforts to ensure proper treatment by borrowing money turned futile. The predicament went on for two years. Nidhi was bed-ridden for a year and passed away in January 2009.

Like Rahasas, Nidhis family too got an APL card only after the tragedy struck the grief-stricken lot. His blank job card exposes the true state of MGNREGA as the villagers hardly get to work under this scheme. Tulsa Dharua, secretary of a self-help group in the village, says: We survive mostly on daily wage work whenever available. MGNREGA has been discouraging due to insufficient work and much-delayed payments.

According to Tulsa, Nidhis family survives on a single meal put together with extreme difficulty. However, this is not an exception as hunger stalks the entire village relentlessly. A debt-ridden Bhumi has now migrated to Cuttack district to work in brick kilns along with her three-year-old son. Barring the APL card, she has no other support; not even the National Family Benefit Scheme (NFBC) benefits -- a one-time compensation of Rs 10,000 she is entitled to since her family has lost the primary breadwinner.

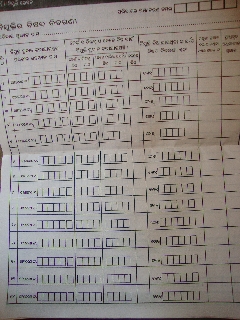

![]() Joba Card of Nidhi Biswal that runs blank inside. Pic: Pradeep Baisakh.

Joba Card of Nidhi Biswal that runs blank inside. Pic: Pradeep Baisakh.

The special rapporteur of NHRC visited these two families in March 2010 to study the cause of deaths. The report has not been made public yet.

Do the scanty sources of livelihood, shoddy implementation of the government welfare schemes, and the poor quantity of food intake of these families indicate chronic hunger as the reason behind the deaths? Any layperson could argue that inadequate food intake makes people physically weak, results in the breakdown of their immunity system, and renders them vulnerable to diseases. Acute poverty also eliminates chances of recovery as the victims families fail to afford proper medical attention.

What is starvation death?

Ironically, starvation death is now an expert subject. Its not the tragedies or the plight of the family members that matters; but the niggling discussion on the definition of hunger by the government, the media, and even some social activists. It is this expertise that often questions the veracity of the reports on starvation deaths.

The Commissioner of Supreme Court Commission on Right to Food Dr N C Saxena and Harsh Mander laid out a starvation protocol. Section 1(i) (definition of starvation) reads: An adult having access to food giving less than 850 kilocalories a day. Similarly, Section 2(i) further explains what constitutes starvation death: It is to be recognised that starvation death does not occur directly and exclusively due to starvation. Victims usually succumb to diseases due to severe food deficit for a long period. The protocol also suggests that while investigating starvation deaths, one should take into account the food and livelihood conditions of the family and examine how the government welfare schemes are operating.

At the time of their deaths, it is clear that the families of Rahasa Bhoi and Nidhi Biswal were stuck in the downward spiral of poverty and disease. Welfare schemes including PDS and MGNREGA did not come to their rescue. Through MNREGA, on an average, only 25 percent of the total card-holders availed 43 days of work in 2009-2010 in the district. Although disputable, these official figures lay bare the failed government intervention to ensure employment to the harried lot, thanks to half-hearted efforts and delayed payments.

Rues Sanjay Mishra, a social activist from Balangir, Due to the delay in BPL survey which was last done in 1997 (Survey 2002 was not implemented), about 35,000 to 40,000 deserving families in the district have been left out of the crucial BPL net. Starvation is inevitable in such families.

Bleak health scenario

What compounds the situation is the decreasing government expenditure on public health, non-availability of medical and paramedical staff, diagnostic services, and medicines in government hospitals. Consequently, the out-of-pocket expenditure among the poor has gone up making access to private medical care almost impossible. In short, death becomes imminent.

Having lost an earning member as well as assets, the family finds it hard to wriggle itself out of debt, poverty, and of course, hunger. Even as the conspicuous absence of government support stares in the face of the affected, starvation deaths get reported. And only occasionally, the lives led in hunger too.

It takes a cursory look to figure out the extent of hunger and poverty dehumanising the people of Balangir and other KBK districts. The need of the hour is to assess the impact of the decreasing spending in the social sector and rationalisation of food subsidy on the poor. The government must accept the reality and ensure effective implementation of major schemes like MGNREGA, PDS, old-age pension, NFBC, emergency feeding, mid-day meal scheme, etc. NGOs, on the other hand, must pressure the government to focus on all-inclusive growth, not just Sensex-driven confabulations.