Femina magazine was quick to capitalize on the rapidly expanding beauty culture with the

publication of numerous fragrance and beauty books. In addition, Femina features inserts in the magazine every few months with

titles like "Skin" and "Scent." In these inserts, which number about twenty graphic and color-rich pages, Editor Amy Fernandes embarks on

an educational project for readers. In a sample issue, elaborate distinctions were made between scents, and readers were informed of the

difference between a woody topnote and a fruity heartnote. The issue included dozens of in-depth descriptions of expensive fragrances.

Issey Miyake's L'eau D'issey, for example, was described as "subtle and elegant. It clings to the skin like an article of clothing and

comes to life on the woman who wears it. A contemporary classic which evokes purity and transparency" (February 2001).

The use of such language to describe fragrance was complicated by a sophisticated analysis of which

Christian Dior lotions work best with which skin types. The back of the magazine carried a price list, and I was quick to note that a

bottle of L'eau D'issey cost about as much as the subeditors at Femina, where I worked for a whole year, earned in one month. The

very fact that the women who help create the language to describe these products cannot afford them points to a serious inequality both

in terms of salary for gendered work as well as the high price which women are willing to pay in order to approximate images of beauty as

they appear in fashion magazines.

The marketing at work behind the beauty industry is fierce and intensely well thought out. Playing on femininity and nationalism,

passages such as the following, taken from an Editor's note to Skin, appeal to women:

An important aspect that Indian women just cannot choose to ignore today is the overwhelming number

of beauties our country is throwing up at international pageants. Aishwarya Rai, Sushmita Sen, Diana Hayden, Lara Dutta, Priyanka Chopra,

Diya Mirza: they're world players on an international stage. Couple that with the superpower India is poised to become. Triple that with

the steadily growing liberal economy and foreign brands arriving at our shores. Can you as a modern woman afford to be left out of it

all? (February 2001).

What message does the reader take away from this? Of course, women are independent agents who negotiate messages far more complex than

this on a daily basis, but, nonetheless, the direct linkage between beauty products and being "left out of it all" is profoundly

disturbing.

This sort of rhetoric has been closely paralleled by changes in images of beauty in Femina. When I asked Editor Sathya Saran about how

these images have changed, she was quick to note: "They've changed amazingly in the last five or six years because of the multinationals

coming in. They brought images of beauty with them which were very different from what we had, and therefore we internationalized our

images of beauty, and today we see that reflected in the way that young women look."

Power of advertising

She was also adamant that international advertising, such as that which inspired the production of inserts like "Skin" and "Scent" had

improved the magazine to such an extent that any woman in the world could pick up Femina and find it comparable to American Vogue. It is

important to remember that a 1994 article entitled, "The Year Ahead for Miss Universe and Miss World" ran next to an ad for, of all

things, Lactonic breast stimulant. It was not until the following year that more relevant and sophisticated advertisements for commercial

beauty products started appearing in the magazine.

Perhaps it is because women do not have a status which is equal to men in most parts of the world that they are

relegated to being objects on display.

I was initially struck by the recommendation for the use of shine serum, rather than the universally available coconut oil, as shine

serum is a comparatively expensive product of which the solidly middle-class target readership of Meri Saheli was most likely not aware.

Its presence, however, serves to underscore the way in which commercial beauty culture has penetrated middle-class life in urban India.

One beauty product that has achieved remarkable success across all class and ethnic groups is the bleaching cream Fair and Lovely.

Something of an institution in India, Fair and Lovely was patented by Hindustan Lever Limited, in 1971 following the patenting of

niacinamide, a chemical that lightens the color of the skin. First test marketed in the South in 1975, it was available throughout India

by 1978 and subsequently became the largest selling skin cream in India. Accounting for eighty percent of the fairness cream market in

India, Fair and Lovely has an estimated sixty million consumers throughout the subcontinent and exports to thirty four countries in

Southeast and Central Asia, as well as the Middle East. In 2000, Fair and Lovely embarked on a new marketing approach, with newer, more

sophisticated packaging and improved fragrance (Hindustan Lever Prospectus, 2002). Even Fair and Lovely, it seemed, was not immune to the

beauty product revolution that introduced new skin care lotions.

The major hurdle that marketing experts had to face in selling cosmetics to urban Indian women was the fact that make up is still

considered somewhat suspect in conservative families. A Hindustan Lever description of the new Jellip brand of lip gloss directly

addressed this problem:

Today's young teenagers can watch out for an exciting and trendy alternative to lipsticks by giving

them the option of giving their lips a subtle hint of color and at the same time softly moisturizing them. The hip and cool Elle 18

Jellip, available in trendy shades, can easily be slipped into a teenager's bag and can form a part of regular college wear. No more will

the young and spirited teenager have to worry about parental disapproval when she wears lip color - because she will not be wearing

lipstick, she will be wearing Jellip! So young girls can go ahead and wear Jellip everyday and sport really cool lip colors!

(Hindustan Lever prospectus 2002).

Only recently have young women had the spending power to allow marketing such a product exclusively to them.

Both Fair and Lovely and Jellip are part of the same pre-liberalization cosmetics giant, Lakmé. Formed after Indian independence in 1947,

Lakmé has exponentially expanded in scope following liberalisation, with the launch of its Elle 18 products for the younger markets and

the opening of a chain of Lakmé beauty salons in eleven cities across India, including Bombay, Chennai, Bangalore, Delhi, Hyderabad,

Pune, Indore, Vadodara, Ludhiana, and Chandigarh, with plans to expand to fifty salons by the end of 2003.

Focusing on the rhetoric of professionalism, Lakmé salons emphasise their high standards in their business plan for franchisees:

Today, the Indian woman's beauty needs are taken care of in neighborhood beauty parlors. In most cases, hygiene is questionable,

customer

satisfaction levels are low and service is far from professional. Compare this with Lakmé beauty salon. Backed by trusted names, Lakmé

and Hindustan Lever, Lakmé beauty salon brings in an air of professionalism to the salon business. From interiors to finance to training,

every single aspect has been meticulously planned to ensure the comfort of the customer and convenience of the franchisees (Hindustan

Lever, Ltd., brochure).

This invitation to franchisees references the parlor, as distinct from the salon. Women themselves also make this distinction in their

own beauty practices; I was firmly criticized once for "wasting money" on a salon manicure, which a friend insisted I should have had

done at a local parlor. The local parlor is considered reliable for simple services such as manicures and pedicures but is not to be

utilized for more complicated procedures, such as straightening hair. The difference between a parlor and a salon is also aesthetic:

while a parlor will be utilitarian and relatively undecorated, a salon will make an attempt at appearing luxurious. The products on offer

will also be more costly, and will most often be international, including beauty products from L'Oreal or Toni and Guy. The Bombay salon

is relatively unique in that it employs male as well as female workers. As the only place where a strange man can touch a woman and this

can still be considered within the realm of acceptability, the salon carries its own eroticism. I recall feeling distinctly uncomfortable

the first time I was given a pedicure by a man at The Mane Event, a salon in the fashionable Bombay neighborhood of Bandra. As he

massaged my calves, I found myself averting my eyes from his, lest he mistake my intentions.

Salons also provide a space in which to cultivate and reaffirm one's own social network. One afternoon at Kaaya, the most well-known

salon in Bombay, which regularly sends its stylists for training in New York and London, I listened in as the conversation drifted from

how frequently Botox needs to be retouched, to one woman's weekend trip to Paris, to a director's desperate search for a lead actress for

his next film. Although I had become accustomed to this kind of banter, I was struck by the way in which, although many in the salon did

not actually know each other, they were drawn into the conversation: within the boundaries of class, it seemed, strangers were free to

talk to one another.

Women seek to replicate international beauty fashion trends on their own bodies, as broader cultural phenomena at large serve to

reinforce newly imported ideas about beauty.

This notion of "translation" speaks to a distinction between a private sense of self, which, following McGrath (2000:35) "includes the

same events and changing relationships that are then experienced through cultural rules" and the more public presentation of that private

self, which is the negotiation of that very experience. Ideas about beauty, both at the corporate and individual, private level, provide

an excellent site for the examination of this, as the physical self is the literal embodiment of the interaction between the two.

Women seek to replicate international beauty fashion trends on their own bodies, as broader cultural phenomena at large serve to

reinforce newly imported ideas about beauty.

A competitive sport

Mere khubsoorati mere sabse bade dushman hain/My beauty is my greatest enemy. (Miss World 1994 Aishwarya Rai, quoted in Meri

Saheli magazine)

Aishwarya's statement resonated with readers throughout India who sympathized with the double-edged sword that being beautiful presents

to women. Beauty is often discursively constructed as dangerous in India, because the beautiful female body is necessarily always an

object of display. Women feel extremely free to comment on the appearance of other women in their presence, noting changes in weight,

appearance, or even overall beauty. I attended one film screening of a recent Aishwarya Rai film with a friend who noted that the

25-year-old actress was "looking really old and haggard." Yet what may appear as a malicious comment is actually a product of a cultural

system that is extremely accustomed to the standardized evaluation of beauty. What is considered beautiful is often very clear - beauty

is fair, tall, and slim, as the matrimonial ads placed by families in search of a bride for their son consistently mention. The practice

of judging women's appearance is deeply ingrained in South Asia, from the practice of "seeing girls," in which young women are brought

for the evaluation of a family as part of a prospective marriage proposal, to the reduction of female bodies to "item numbers" who do

nothing but perform undulating dance sequences in Hindi films.

Women hate each other. If you are beautiful, women will always hate you. I tell my sister, if you don't have any friends, it's ok, you

can't help it if you're beautiful. Like me, I dress down all the time, so women don't feel threatened by me. It's only when I'm out with

other beautiful women that I dress up too, like with you. I would never feel threatened with you, because you're more beautiful than me.

This statement, taken from my interview with a young woman who works in the beauty industry, is loaded with sentiments that speak of a

lifetime's experience. While the speaker describes women as enemies because of their desire to be beautiful, she also positions herself,

her sister, and me in a discursive hierarchy of beauty that is non-negotiable in character. So while she constructs her sister's social

isolation as a result of her beauty, she also positions herself as outside of this hierarchy in relationship to me, who she believes to

be more beautiful than her.

Statements such as these are common in Bombay. Beauty is nonnegotiable; something that is a fact that needs no further explanation. Women

will describe each other as "my beautiful friend," using the adjective as freely as any other in the course of conversation as they would

a description of height or weight, or even their own lives in this way. For example, it is not uncommon to hear women say "it was because

I am beautiful" as a way of explaining why an event transpired in a particular way.

Pruned and packaged

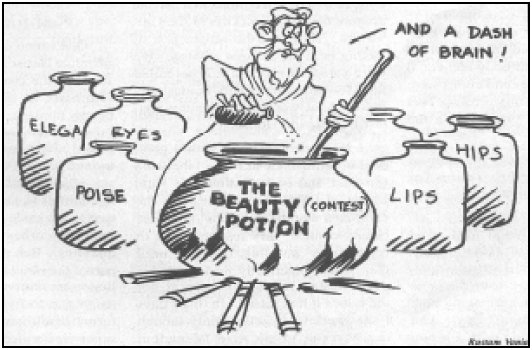

As such, I contend that there are some cultural systems that lend themselves particularly well to the commoditisation and packaging of

female beauty. Although beauty pageants are a profoundly capitalist phenomenon in the sense that they, at a very basic level, use women's

bodies in order to market products, they are also cultural performances in which ideas about femininity and beauty are reinforced.

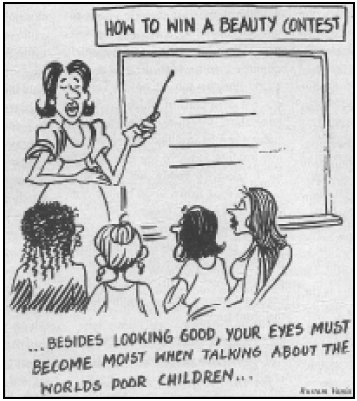

At the Miss India 2002 semi-finals, presenter and former model Malaika Arora casually announced that "contrary to popular belief that

women are women's own worst enemies, this group has been supportive of one another." It was the offhand tone of this remark, which

positioned it as fact rather than point of discussion, that truly disturbed me. As a cultural observer doing fieldwork, I felt

consistently uneasy about a system that pits women against each other.

The concept of beauty as a competitive sport is perhaps nowhere more evident than in the Hindi film and media industry, which are

dangerously confused with everyday life by many women. It is perfectly normal, even expected, that women will comment on the appearance

of women they see on films, on television, and in everyday life. Women are discursively constructed as always being onstage. Female

friends who belong to the milieu of cosmopolitan elites routinely greet each other after an absence of just a few days with observations

on weight loss or gain, on clothing, or on other aspects of physical appearance. Although I have always been rather conscientious of my

appearance, it took several months in the field before I was able to become fully accustomed to being judged on my appearance as a matter

of routine by women I considered my friends.

Perhaps it is because women do not have a status which is equal to men in most parts of the world that they are relegated to being

objects on display. Public space in India, even in urban areas, is considered more of a male domain. Therefore, it is fairly normal,

despite being considered socially unacceptable, for men on the street to comment on the appearance of women or to serenade them with love

songs from Hindi films, habits which irritate the majority of women to no end.

Masculine public spaces

Although public space in Bombay, as in the rest of South Asia, is dominated by men, women negotiate this gendered space in a variety of

ways. The powerful distinction between inside/outside and female/ male provides an important means by which women judge which areas and

forms of dress are appropriate. Elite women in more revealing clothes negotiate public space by staying in cars en route to spaces where

such attire is appropriate, such as clubs, as well as by wearing loose shirts over tight or revealing clothing. One embarrassing

illustration of this occurred as I stepped out of a taxi and accidentally broke the heel of my shoe and tore the loose shirt I was

wearing on my way to meet a friend for dinner in Breach Candy, an elite neighborhood in South Bombay. Realising that I needed to fix the

heel, I walked across the street to a cobbler and put the torn shirt, my insurance against stares, in my bag. I remember feeling

extremely uncomfortable standing on the street for the few minutes that it took to fix my shoe, because it was public space, and then

walking into the Breach Candy restaurant where every single other woman was wearing the same type of clothing as me; the only difference

was that they were only wearing it inside, whereas circumstance had forced me to wear it outside, which forced me to feel the difference

between myself and the people on the street.

Going out at night is often discursively constructed as fraught with danger for women, especially since the type of behavior that seems

very normal in the space of the nightclub, such as conversations about sexuality that more often than not have an androcentric tone, are

anything but normal in other spaces. Indeed, the one night that the Miss India contestants were taken out to celebrate New Year's Eve,

they were taken to a nightclub that was closed to the public. This was done in an attempt to ensure that they would not receive undue

amounts of unpleasant male attention.

I was often advised by well-intentioned men not to go out at night throughout the course of my fieldwork. The following example from a

film producer illustrates this:"You're a nice girl, Susan. You're not like these Bombay women. See, once a man sees you smoke, he

automatically assumes that you drink and do all sorts of other bad things."

The postliberalization actress is easily identifiable: she is all too recognizable with her long hair (poker straight), height (over

5'6"), tiny waist (belly button exposed), and tight-fitting clothes - she is post-liberalization, post-modern India's most ubiquitous

icon. A made-to-order film star, she represents a lot and stands for very little.

Yet the concept of "normal" is fraught with complexity in the space of the cosmopolitan project. Those who are active participants in the

cosmopolitan project have very little in common with the rest of the city, and active participants feel fundamentally disconnected from

the rest of Bombay. And because the participants in the cosmopolitan project are such a minority in comparison to the rest of Bombay,

their standards of behavior are highly relative and extremely fluid in terms of what is acceptable. Going out at night, for example,

where the sexual attention of men who are discursively constructed as attractive might be viewed by women as an exciting and inevitable

part of participating in the world as described in the media, in which all moral standards are relative. However, it is also crucial that

these women maintain a public face of respectability in order to get married.

Bombay's sharp division between those who are conservative and those who participate in the cosmopolitan project leaves many, if not all,

individuals with conflicting desires surrounding identity and what it means to internalize the cosmopolitan project by inscribing it

within one's life in various degrees. Bombay, after all, is not a cosmopolitan city; it is however, home to participants in a

cosmopolitan project whose presence, in turn, affects the character of the city. Individuals often contend that women have access to a

lifestyle in Bombay that is simply not possible in the rest of India. As Devesh Sharma, the CEO of the nightclub Mikanos noted:

People have become more civilized. That's why Bombay is so great, because a woman can come into the club and rest assured that she can

have a great night, and a safe time, without a second thought.

Devesh's reference to people becoming "more civilized" is itself a reference to the cosmopolitan project's shift in terms of behavioral

norms. However, the fact that he feels the need to point out that a woman in Bombay can have a "safe time" points to the notion that

predominantly male spaces have the potential to be unsafe. Defending oneself against the danger, both perceived and real, of male public

space is a fairly common topic of female discussion, albeit in various forms.

Arvind Khaire teaches a self defense course for women that is intended to prepare them for potential attacks that might occur in male

space. Khaire contends that women need to possess public space and not be afraid:

"Women are brought up to be submissive. Even in my class, if they hit somebody they are always saying

"sorry, sorry" and trying to be nice. Women need to think right to be able to defend themselves, because society has conditioned them not

to assert themselves. Women need to practice my techniques every day, and they will be effective on the road.

Particularly interesting is Khaire's reference to "the road," as it implies that women face danger only in the sphere of public space.

Since the economy opened to foreign investment, the resulting influx of European and American images of beauty have deeply impacted the

notion of what a beautiful actress looks like. In fact, many avid consumers of popular culture in India have commented on how "all

heroines (actresses) look the same." The postliberalization actress is easily identifiable: she is all too recognizable with her long

hair (poker straight), height (over 5'6"), tiny waist (belly button exposed), and tight-fitting clothes - she is post-liberalization,

post-modern India's most ubiquitous icon. A made-to-order film star, she represents a lot and stands for very little. She cannot truly be

called an actress, as she often has little to do in a film except sigh and pout, yet she is on every film screen, a beauty accessory.

There are a million other women who look exactly like her, which makes competition for work extremely stiff. In an era in which beauty is

perhaps more rigidly defined than it ever has been, the image of what a heroine or model should be is becoming more and more

circumscribed into a very specific physical type. Although young women have, for better or worse, been largely defined and measured by

their beauty for centuries, the decade-old media explosion in India has meant that more and more young women are interested in the

glamour industry as a viable career option. This interest, combined with the very lucrative rewards such a career promises, as well as

changing norms for female behavior, has meant incredibly tough competition among women. The question remains, however, that with so many

talented women available and ready for work, why are they all doing the same thing?

Actress Antara Mali's role in the recent film Road is emblematic of this. Road, a film by director Ram Gopal Varma, depicts the

adventures of an elite, urban young couple as they elope to another city to get married. The young couple was equipped throughout the

film with all the accoutrements of post-liberalization perfection: sculpted bodies, fashionable clothing, and an expensive car. The film

was as much an adoration of the actress' body as it was about the storyline and often resembled a music video more than a film in the way

that the cinematography focused on the actress' body from scene to scene.

As I walked out of the cinema after seeing the film, I said to my friend, "They should have called this movie Antara Mali ki kamar

(Antara Mali's waist)." He laughed, because he knew exactly what I was talking about - the director's eye had languished long and

lovingly on Antara's tiny waist throughout the film. Unfortunately, the film left me with few other impressions of her acting abilities.

This is not so much a condemnation of Mali's acting abilities (or lack thereof) as it is symptomatic of the Hindi film industry's refusal

to provide interesting roles for women. Unfortunately, this trend has expanded to encompass the entire field of media in India, from film

to advertising. As such, women in media are presented with few options outside of presenting a glamorous image that has little substance

behind it.

However, there are exceptions to this rule. Kim Jagtiani, who is a presenter on Channel V, is adamant that, although the channel may have

chosen her because she had won the Miss India-Canada pageant, she would not allow them to package her into something that she is not. She

observes:

They started out putting me into this sex bomb, sexy kind of image, with the clothes and all. That's

not me, and the audience could see that. I'm more of a tomboy, when it comes to clothes and all. Delivery makes a difference when it

comes down to what you're wearing, and when I started wearing my own stuff, then I gained the image of the girl next door. This whole

stand proper, with your hips and waist like this, that's just not me.

Yet while Kim was able to negotiate the way Channel V packaged her because she came in as the winner of a beauty pageant considered

prestigious in India, most women are unable to do the same. In the beauty pageant of everyday life, things are no different. As a writer

for a prestigious fashion magazine in Bombay noted, "Now, the glamourization of life makes it so women are always judging each other."

Indeed, the pressure is enormous. Economic liberalisation, with its frightening onslaught of beauty products and narrowly defined images

of beauty, has seriously aggravated and complicated problems that women always have faced about how they are seen.

Susan Runkle

This article is drawn from the PhD thesis of the author who is affilated with the Anthropology Department of Syracuse University.

![]() The beauty obsession

The beauty obsession

Since the economy opened to foreign investment, the influx of European and American images of beauty have deeply impacted the

notion of what it is.

Susan Runkle

notes how over the last decade,

international standards for fair and lovely have taken firm hold.

Urban India's middle and upper class women have experienced a veritable revolution in commercial beauty products and beauty culture since

liberalization in 1991. Prior to liberalization, these women had two brands of lipstick and cold cream from which to choose. In the last

five years, however, zaibatsu giant Hindustan Lever, Ltd., released 250 new beauty products, and international corporations have been

heavily involved in marketing beauty products in India. French cosmetics giant L'Oreal, for example, has spent over thirty million

dollars on local manufacturing since 1994. During an interview, S. Jayabalan, Managing Director of Kalinga Cosmetics, which handles

international brands such as Kenzo, stressed the importance of international trends in Indian consumption patterns: "Indians are very

brand conscious. They are well aware of all the popular brands abroad like Issey Miyake and Lancome. What's popular abroad is very

popular here."

![]() Interestingly, these extensive ads for commercial beauty products are not restricted to elite English language magazines. The Hindi

language Meri Saheli (My Girlfriend) routinely features beauty advice that increasingly relies on the use of products that are bought,

rather than made, at home to beautify oneself. The October 2002 issue advised: "âgar bal daumûhe hô gaye ho aur bal kô trim karne ka

samay na ho to hair shine serum lagâa Isse daumûhe bal chip jâyengç/ (If you have split ends and do not have time for a trim, apply hair

shine serum. This will hide your split ends)."

Interestingly, these extensive ads for commercial beauty products are not restricted to elite English language magazines. The Hindi

language Meri Saheli (My Girlfriend) routinely features beauty advice that increasingly relies on the use of products that are bought,

rather than made, at home to beautify oneself. The October 2002 issue advised: "âgar bal daumûhe hô gaye ho aur bal kô trim karne ka

samay na ho to hair shine serum lagâa Isse daumûhe bal chip jâyengç/ (If you have split ends and do not have time for a trim, apply hair

shine serum. This will hide your split ends)."

![]() Within a certain milieu, it is entirely possible, as well as acceptable, to spend an entire day at the salon. As a uniquely female

pursuit, then, beauty becomes something of a hobby for many well to do women, who structure their weeks around when to have which service

performed for them. However, certain markers of beauty are more class-based than others. For example, having highlights is a highly

coveted symbol of high status. Hair color is a fairly recent newcomer to the urban India beauty scene. At a hair show by L'Oreal that I

attended at a five-star hotel in Bombay, the French hair stylists were insistent that the stylists in the audience learn how to "become

fashion translators, not fashion victims." As the press release for the event lauded, the event hoped to "not only give a window to

trends overseas but also allow hairdressers here to blend international styling trends and techniques with local preferences and thus

retain their individuality."

Within a certain milieu, it is entirely possible, as well as acceptable, to spend an entire day at the salon. As a uniquely female

pursuit, then, beauty becomes something of a hobby for many well to do women, who structure their weeks around when to have which service

performed for them. However, certain markers of beauty are more class-based than others. For example, having highlights is a highly

coveted symbol of high status. Hair color is a fairly recent newcomer to the urban India beauty scene. At a hair show by L'Oreal that I

attended at a five-star hotel in Bombay, the French hair stylists were insistent that the stylists in the audience learn how to "become

fashion translators, not fashion victims." As the press release for the event lauded, the event hoped to "not only give a window to

trends overseas but also allow hairdressers here to blend international styling trends and techniques with local preferences and thus

retain their individuality."

As such, it often struck me as extremely odd that critics of beauty pageants in India would criticize them as "Western." After an entire

lifetime spent in a place discursively constructed as "the West," I have a difficult time remembering if I have ever actually seen a

beauty pageant there. True, they have originated in the West. However, today in the West they do not carry the kind of status and clout

they have come to acquire in South Asia. Indeed, the concept of objectively judging beauty is as widespread in South Asia as it is not in

the West.

As such, it often struck me as extremely odd that critics of beauty pageants in India would criticize them as "Western." After an entire

lifetime spent in a place discursively constructed as "the West," I have a difficult time remembering if I have ever actually seen a

beauty pageant there. True, they have originated in the West. However, today in the West they do not carry the kind of status and clout

they have come to acquire in South Asia. Indeed, the concept of objectively judging beauty is as widespread in South Asia as it is not in

the West.

•

Manufacturing beauties

![]() "All sorts of other bad things" in South Asian parlance generally refers to sexualised forms of behavior, as the dangers that result from

going out are primarily sexual ones. Because certain "sets" of more malebiased behavior, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and overt

sexuality are often lumped together in South Asia, women who present themselves within the cosmopolitan space in which these behaviors

are normal risk having all of these behaviors ascribed to them should they choose to engage in any one of them.

"All sorts of other bad things" in South Asian parlance generally refers to sexualised forms of behavior, as the dangers that result from

going out are primarily sexual ones. Because certain "sets" of more malebiased behavior, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and overt

sexuality are often lumped together in South Asia, women who present themselves within the cosmopolitan space in which these behaviors

are normal risk having all of these behaviors ascribed to them should they choose to engage in any one of them.

Manushi, Issue 145

(published February 2005 in India Together)

-

Feedback:

Tell us what you think of this article