We were sad, not because we were outnumbered, not even because the Bill was passed unanimously, but because of the manner in which an

important issue relating to women was discussed, the comments that were passed on the floor of the House, by our elected representatives,

who are under the constitutional mandate to protect the dignity of women! Subsequently, we have heard rumours that some of these comments

have been withdrawn and will not be reflected in the reported proceedings. But this cannot obviate the fact that this is the way our

elected representatives think about women.

One of the comments was aimed at us. 'These women who are opposing the ban, we will make their mothers dance ... .' (The comments have to

be translated into Marathi to gauge its impact.) During the campaign we had been asked, 'Will you send your daughter to dance in a bar?'

But on the floor of the House, the situation had regressed, from our daughters to our mothers! They sniggered: "Isha Koppikar ... she is

an atom bomb, atom bomb ... " This evoked great deal of laughter and cheer ... "The dancers wear only 20 per cent clothes" ... More

laughter and cheering ... "These women who dance naked (nanga nach), they don't deserve any sympathy". A round of applause.

An esteemed member narrated an incident of his friend's daughter who had committed suicide because she did not get a job. He said it was

more dignified to commit suicide than dance in bars. And the House applauded! The message for women is clear: If you happen to be born in

a poor family, you are better off dead! Yet another congratulated the Deputy Home Minister for taking this bold and revolutionary step,

but this was not enough. He urged that "hotels with three stars ... five stars, disco dancing ... belly dancing ... all that is

vulgar ... every thing should be banned, except Bharatnatyam and Kathak."

How will the state effect this ban, when through its own admission out of around 1300 dance bars only 307 are legal and authorized?

Then another esteemed member declared, 'We are not Taliban, but somewhere we have to put a stop. The moral policing we do, it is a good

thing, but it is not enough ... we need to do even more of this moral policing.' Suddenly the term 'moral policing' had been turned

into a hallowed phrase!

These comments were not from the ruling party members who had tabled the Bill. They were from the Opposition. Their traditional role is

to criticize a bill, to puncture holes in it, to present a counter viewpoint. But on that day, the House was united across party lines

and all were playing to the gallery with their moral oneupmanship. Even the Shiv Sena whose party high command is linked to a couple of

dance bars in the city, supported the ban. And the Marxists were at one with the Shiv Sainiks. The speech by the CPI(M) member was

more scathing than the rest. The women members, though a small minority, happily cheered the barrage against bar dancers.

The 'morality' issue had won. The 'livelihood' issue had lost.

How the state will effect this ban, when through its own admission out of around 1300 dance bars only 307 are legal and authorized, is

something we will have to wait and watch.

Liquor and entertainment

The bar dancer is a part of the city's thriving nightlife. Bombay never sleeps. The city is hailed as the crowning glory of the nation's

entertainment industry. From the time when the East India Company developed Mumbai as a port and built a fort in the seventeenth century,

Bombay has been a city of migrants. Migrants come to the city in search of livelihoods and with the workers have come the entertainers.

The city of migrants - predominantly male migrants - also needed cheap eating-places. To cater to their needs initially there were Irani

restaurants, Chilia (Muslim) restaurants and later South Indian (Udupi) joints and Punjabi dhabas.

The prevalence of dance bars is linked not only to the restaurant industry and the entertainment business, but also to the state policy

on the sale of liquor. After Independence, during the fifties, when Morarji Desai was Chief Minister, the State of Bombay was under

prohibition and restaurants could not serve liquor. But after Maharashtra severed its links with the Gujarat side of the erstwhile Bombay

Presidency, the newly formed state reviewed its liquor policy and the prohibition era was transformed into the 'permit' era. A place

where beer was served was called a 'permit room'. Only a person who had obtained a 'permit' could sit in a permit room and drink beer.

But gradually, the term 'permit room' lost its meaning and the government went all out to promote liquor sale in hotels and restaurants.

It was during this period, sometime in the seventies, that permit rooms and beer bars started introducing innovative devices to beat

their competitors - live orchestra, mimicry and 'ladies service bars' where women from the red light district were employed as

waitresses.

The licenses to hold performances were issued under Rules for Licensing and Controlling Places of Public Amusement (other than Cinemas)

and Performances for Public Amusement including Melas and Thamashas, 1960. But soon the low quality orchestra and gazal singing lost its

sheen. Some bars then introduced live dance performances to recorded music or live orchestras. Around this time, Hindi films also started

introducing sexy 'item numbers' and the dancers in the bars imitated these item numbers during their performances.

The Government also issued licenses for performance of 'cabaret shows'. A place that was notorious for its lewd and obscene cabaret

performances is 'Blue Nile' which was constantly raided and was entangled in lengthy litigation. It was this litigation that forced the

High Court to examine the notion of obscenity under S.294 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), an issue I will deal with more elaborately

later in this essay.

Soon the sale of liquor and consequently the profit margins of the owners recorded an upward trend. This encouraged the owners of other

Irani 'permit room' restaurants, South Indian eateries and Punjabi dhabas to convert their places into dance bars. Coincidentally, during

the same period, the mujra culture in Mumbai was facing loss of patronage and was on the decline. As the waitresses in the 'ladies

service bars' during this early period were from Kamathipura, which also housed the mujras, this new demand for bar dancers reached these

traditional dancers and many sought jobs in dance bars. Even for daughters of sex workers, this was a step forward - from brothel

prostitution to dance bars.

Soon the phenomenon of 'dance bars' spread from South Bombay to Central Bombay, to the Western and Central suburbs, to the satellite

cities of New Bombay and Panvel, and from there, along the arterial roads, to other smaller cities and towns of Maharashtra. From a mere

24 dance bars in 1985-86, the number increased tenfolds within a decade to around 210. The next decade 1995-2005 witnessed yet another

phenomenal increase. As per a rough estimate, presently there are around 1300 dance bars in Maharashtra.

Women from traditional dancing / performance communities... who were facing a decline in patronage of their ageold profession, flocked to

Mumbai to work in dance bars. Even for daughters of sex workers, this was a step forward - from brothel prostitution to dance bars.

Apart from these traditional dancing communities, women from other poor communities also began to seek work in these bars as dancers.

These women are mainly daughters of mill workers. With the sole earner having lost his job after the closure of the textile mills, young

girls with more supple bodies and the sex appeal of their youth entered the job market to support their families. Similarly endowed women

who had worked as domestic maids, or in other exploitative conditions as piece-rate workers, or as door to door sales girls, as well as

women workers who had been retrenched from factories and industrial units, also found work in dance bars.

In short, the dance bars opened up a new avenue of employment to women from the marginalized sections. It is the paucity of jobs in other

sectors, and the boost given by the Maharashtra government to the active promotion of liquor sales that led to the proliferation of dance

bars. The maximum proliferation occurred during the Shiv Sena-BJP rule in the nineties.

While the business of dance bars flourished in the State, the State administration did not frame any rules to regulate the performances

until 2001. The bar owners functioned under regular licenses issued to restaurants and bars. They paid Rs.55,000 per month for the

various permits and licenses to the Muncipal Corporation. They also paid an annual excise fee of Rs.80,000. In addition the bar owners

also pay Rs.30, 000 per month to the Collector by way of "entertainment fee". But the maximum gain to the State Government was the 20 per

cent sale tax on liquor. As the liquor sales increased, so did the profits of the bar owners and the revenue for the state.

The official charge for police protection was a mere Rs. 25 per night and the stipulated period for closing the bars was 12.30 am. But in

this Hafta Raj most bars remained open till the wee hours of morning. Only when the haftas (bribes) did not reach the officials in time

the bars would be raided. The grounds for raiding the bars were:

After a raid licenses were sometimes either suspended or revoked. But the bar owners say that the government always came to their rescue.

They could approach the Home Department for cancellation of the suspension orders issued by the police or for getting the revoked

licenses re-issued. All this for a fee!

But something went wrong in late 1998. Suddenly, when Gopinath Munde of the BJP was the Deputy Chief Minister (DCM), 19 bars were raided

in a single night. The State Government also declared a hike of 300 percent in the annual excise fee, lifting it from Rs. 80, 000 to

2,40,000. It was at this point that the bar owners decided to organize themselves. Around 400 bar owners responded to a call given by one

Manjeet Singh Sethi; later they formed an association called, 'Fight for the Rights of Bar Owners Association' which organised an

impressive rally on February 19, 1999.

In order to work out a compromise, the Association approached the then Commissioner of Police from the ruling Congress Party, assured him

of their

cooperation, and sought his intervention to end the Hafta Raj. They claim that they had evolved an internal monitoring mechanism to

ensure that all bars abide by the stipulated time for closing down. But the local police stations were most unhappy at their potential

loss of bribes. They tried to break the unity among the members of the Association. For example, when the Bar Owners Association tried to

take action against those of their members who violated the agreed upon rules, the police came to their rescue. The police benefited when

bar owners violated the rules and consequently pay regular haftas. Over a period the regular haftas paid by each bar owner to the police

increased and just before the recent ban, each bar owner was allegedly paying Rs.75,000 per month by way of bribes to the Deputy Police

Commissioner (DCP) of their zone. Some of this money then trickles down the police ladder from the DCP to the lowest ranking constable in

predetermined proportions.

When the bars are raided, it is the girls who are arrested, but the owners are let off. During the raids the police molest them, tear

their clothes, and abuse them in filthy language.

The BJP-Sena alliance lost the 1999 Assembly elections and there was a change of regime. The Association started fresh negotiations with

the ruling Congress- NCP. They greased the palms of high ranking politicians to allow them to officially stay open more hours, from 12.30

am to 3.30 a.m. so that there would be no need to pay regular haftas for this particular violation. After much negotiation, on January 3,

2001, the first ever regulation regarding dance bars came through a government notification. The bars were granted permission to keep

their places open till 1.30 a.m. But somewhere the negotiations backfired, or perhaps the right palms were not sufficiently greased. The

government decided to increase the police protection charges from Rs.25 to Rs.1500 per day per dance floor. The angry bar owners held

rallies and approached the courts. Due to court intervention, the hiked fees were brought down to Rs.500 per night.

Bar owners claim that the police raids increased after a Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) security guard outside a bar beat up a worker

in the late hours in the month of February, 2004. Following this, 52 bars were raided in February, and 62 in March 2004. The bar owners

alleged that the raids are politically motivated and were connected to the forthcoming State Assembly elections. The ruling Congress

Party denied these charges and accused the bar owners of indulging in trafficking of minors. The bar owners approached the High Courts,

and several FIRs filed by the police were quashed. Again on July 30, bars were raided. This time, the bar owners filed a Writ Petition in

the Bombay High Court and sought protection against constant police harassment. They also organized a

huge rally at Azad Maidan on August 20, 2004. An important feature of this rally was the emergence of the Bar Girls' Union on the

political scenario.

Bar girls claim attention

The mushrooming of an entire industry called the 'dance bars' had escaped the notice of the women's movement in the city despite the fact

that several groups and NGOs had been working on issues such as domestic violence, dowry harassment, rape and sexual harassment. Everyone

in Mumbai is aware that there are some exclusive 'ladies bars', but usually women, especially those unaccompanied by men, are stopped at

the entrance. Occasionally, when a bar dancer was raped and/or murdered, women's groups had participated in protest rallies organized by

local community based groups, more as an issue of violence against women than as a specific engagement with the day to day problems of

bar dancers.

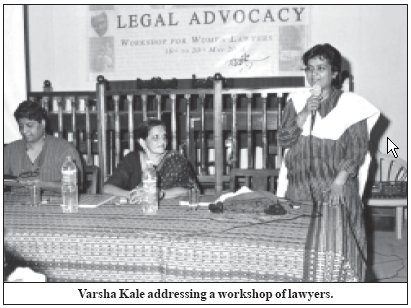

The August 20 rally in which thousands of bar dancers had participated received wide media publicity. The newspapers reported that there

are about 75,000 bar girls. On the day of the rally, a television channel had invited me to give my reaction to the protest by bar

dancers. I had welcomed it as a positive step. That was my first interaction with the issue of bar dancers. Soon thereafter, Ms. Varsha

Kale, the President of the Bar Girls Union approached me and requested me to represent them through an 'Intervener Application' in the

Writ Petition filed by the bar owners. Varsha is not a bar dancer, she belonged to a women's group in Dombvili (in the Central suburbs of

Mumbai).

Since the issue was new and out of the purview of the regular matrimonial litigation with which our organization, Majlis, is involved, we

were confused. Varsha explained to us that while for the bar owners it was a question of business losses, for the bar girls it was an

issue of human dignity and right to livelihood. When the bars are raided, it is the girls who are arrested, but the owners are let off.

During the raids the police molest them, tear their clothes, and abuse them in filthy language. At times, the girls are retained in the

police station for the whole night and subjected to further indignities. But in the litigation, their concerns were not reflected. It is

essential that they be heard and they become part of the negotiations with the State regarding the code of conduct to be followed during

the raids.

As far as the abuse of power by the police was concerned, we were clear. But what about the vulgar and obscene display of the female body

for the pleasure of drunken male customers, which was promoted by the bar owners with the sole intention of jacking up their profits? It

is here that we lacked clarity. I had been part of the women's movement that has protested against fashion parades and beauty contests

and semi-nude depiction of women in Hindi films. But my colleagues, Veena Gowda and Shreemoyee Nandini - both young, dynamic, women's

rights lawyers, belonged to a later generation which had come to terms with fashion parades, female sexuality and erotica.

Differing feminist perceptions

Finally after much discussion, we decided to take on the challenge and represent the Bar Girls' Union in the litigation. We invited some

of the girls who had been molested to meet with us. Around 35 to 40 girls turned up. We talked to them at length. I also decided to visit

some bars. Though I was uncomfortable in an environment of palpable sexual under-currents, I felt that the difference between a bar and a

brothel is significant. An NGO, Prerana, which works on anti-trafficking issues, had filed an intervenor application, alleging the

contrary - that bars are in fact brothels and that they are dens of prostitution where minors are trafficked. While the police had raided

the bars on the ground of obscenity, the Prerana intervention added a new twist to the litigation because they submitted that regular

police raids are essential for controlling trafficking and for rescuing minors. The fact that the police had not abided by the strict

guidelines in anti-trafficking laws and had molested the women did not seem to matter to them.

Opposing a fellow organisation with which I had a long association was extremely uncomfortable. Prerana had been working with sex workers

and had started an innovative project of night crèches for children of sex workers in Kamathipura way back in 1986-87. I had been

involved with several para-legal workshops organized by Prerana for sex workers. During these workshops the main concerns for the sex

workers were police harassment and arbitrary arrests. I viewed my intervention on behalf of bar girls as an extension of the work I had

done with Prerana, but Prerana members felt otherwise. At times, after the court proceedings, we ended up being extremely confrontational

and emotionally charged, with Prerana representatives accusing us of legitimizing trafficking by bar owners and us retaliating by

accusing them of acting at the behest of the police.

Under garb of morality

From September 2004 to March 2005, the case went through the usual delays. In March, when the case came up for arguments, the lawyer for

the bar owners produced an affidavit by the complainant, upon whose complaint the police had conducted the raids. The same person had

filed the complaint against nine bars in one night. The police officials themselves admitted that he was a 'professional' pancha (police

witness). The second person who had filed the complaint was a petty criminal. In the affidavit produced by the bar owners, the

professional pancha stated that he was not present at any of the bars against whom he had filed the complaints and the complaints were

filed at the behest of the police.

This rocked the boat for the police and invited the wrath of the judges against them. They were asked to file an affidavit explaining

this new development. This turned out to be the last day of the court hearing. Before the next date, the DCM R. R. Patil had already

announced the ban. So in view of this, according to the police prosecutor, the case had become infructuous.

The sex worker is viewed with more compassion than the bar dancer, who may or may not resort to sex work.

The police had conducted raids on a dance bar in Nagpur and initiated criminal proceedings against the owners as well as the dancers on

grounds of obscenity and immorality. The bar owners had approached the High Court for quashing the proceedings on the ground that the

raids were conducted with a malafide intention by two IPS officers who had a grudge against them. In his affidavit filed before the High

Court, the Joint Commissioner of Police, Nagpur stated as follows: "It is found that certain girls were dancing on the floor and were

making indecent gestures. The girls were mingling with the customers, touching their bodies, and the customers were paying money to

them."

On April 4, 2005, Justice A. H. Joshi presiding over the Nagpur Bench of the Bombay High Court quashed the criminal proceedings initiated

by the Police on the ground that the case made out by the police does not attract the ingredients of Section 294 of the IPC. Section 294

is attracted only when annoyance is caused to another, due to obscene acts in a public place. The Court held that the affidavit filed by

the Joint Commissioner of Police did not reveal that annoyance was caused to him personally or to any other viewer due to the alleged

obscene dancing.

This ruling followed several earlier decisions by the Bombay High Court, which had addressed the issue of obscenity in dance bars. One of

the earliest rulings on this issue is by Justice Vaidhya in the State of Maharashtra v Joyce Zee alias Temiko in 1978 where the court

examined whether cabaret shows constitute obscenity. The police had conducted raids in Blue Nile and had filed a case against a Chinese

cabaret artist, Temiko, on grounds of obscenity.

Ban on dance bars

The DCM's statement announcing the ban was followed by unprecedented media glare, and we found ourselves in the centre of the controversy

as lawyers representing the Bar Girls' Union. The controversy had all the right ingredients - titillating sexuality, a hint of the

underworld, a faintly visible crack in the ruling Congress-NCP alliance, and polarized positions among social activists.

The controversy was not of our own making but we could not retract now. We threw in our lot with that of the Bar Girls' Union. The bar

girls petitioned to the Chief Minister, the National and State Women's Commissions, Commissions for ST, SC and Backward Castes, the Human

Rights Commissions, and the Governor, S.M Krishna. We even met Sonia Gandhi, the Congress President and sought her intervention. Other

women's groups joined in and issued a statement opposing the ban.

Is it her earning capacity, the legitimacy awarded to her profession, and the higher status she enjoys in comparison to a sex worker that

invite the fury from the middle class Maharashtrian moralists?

An equal or even greater number of NGOs and social activists issued statements supporting the ban. The child-rights and anti-trafficking

groups led by Prerana issued a congratulatory message to the DCM and claimed that they had won. Then women members of the NCP came on the

street brandishing the banner of depraved morality. The Socialists and Gandhians joined them with endorsements from stalwarts like Mrinal

Gore and Ahilya Rangnekar to aid them. These statements had the blessings of a retired High Court judge - Justice Dharmadhikari. Paid

advertisements appeared in newspapers and signature campaigns were held at railway stations. 'Sweety and Savithri - who will you choose?'

goaded the leaflets distributed door to door, along with the morning newspaper. The term 'Savithri', denoted the traditional pativrata,

an ideal for Indian womanhood, while 'Sweety' denoted the woman of easy virtue, the wrecker of middle class homes.

Interestingly, the Gandhians seem to be only against the dancers and not against the bars that have proliferated. Nor have they done much

to oppose the liquor policy of the State, which had encouraged bar dancing. The antitrafficking groups who had been working in the red

light districts had not succeeded in making a dent in child trafficking in brothels that continue to thrive. But in this controversy,

brothel prostitution and trafficking of minors has been relegated to the sidelines. The sex worker is viewed with more compassion than

the bar dancer, who may or may not resort to sex work.

Targeting the vulnerable

The bar dancer is being made out to be the cause of all social evils and depravity. Even the blame for the Telgi scam is laid at her

door; the news story that Telgi spent 93 lakhs on a bar dancer in one night is cited as an example of their pernicious influence. The

criminal means through which Telgi amassed wealth fades into oblivion in the fury of the controversy. Is it her earning capacity, the

legitimacy awarded to her profession, and the higher status she enjoys in comparison to a sex worker that invite the fury from the middle

class Maharashtrian moralists?

The ban will not affect the bars. The profit margins may go down for a while, but soon other devices will be found to promote liquor

sale. Bars employ women as waitresses and the proposed ban will not affect this category. Waitresses mingle with the customers more than

the dancers who are confined to the dance floor. If the anti-trafficking laws have not been successful in preventing trafficking, how

will ban on bar dancing prevent trafficking? And if certain bars were functioning as brothels, why were the licenses issued to them not

revoked?

Physician heal thyself

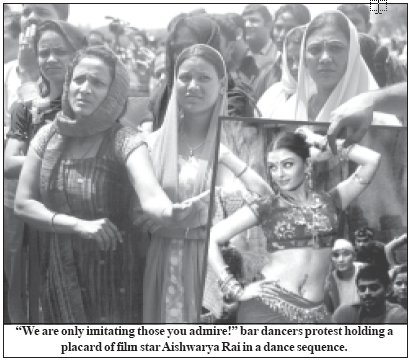

While the hue and cry about the morality of dance bars was raging, in Sangli district, the home constituency of the Deputy Chief Minister

(DCM), a dance performance titled 'Temptation' by Isha Kopikar, the hot selling 'item girl' of Bollywood, was being organized to raise

money for the Police Welfare Fund. The bar girls flocked to Sangli to hold a protest march. This received even more publicity than the

performance by Isha Kopikar who, due to the adverse publicity, was compelled to dress modestly and could not perform in her usual

flamboyant style. The disappointed public felt it was more value for their money to see the protest of the bar girls than to witness a

lack luster performance by the 'item girl'. And the bar girls raised a pertinent question, whether different rules of morality apply to

the police and the Home Minister.

Another controversy surfaced when the late Sunil Dutt, the popular and highly respected Congress MP from Mumbai, as well as Govinda, the

newer entrant to politics and also a Congress MP from North-West Mumbai, issued statements opposing the ban. Govinda himself hails from a

performer community. And Sunil Dutt had responded as a performer. Justice H. Suresh, a retired Bombay High Court judge and well-known

defender of human rights also opposed the ban.

All this has been heady news for the television channels and the tabloids. 'Dance Bars to Sex Bars' blared a recent tabloid headline,

which splashed photographs allegedly taken from a hidden camera. The report stated that desperate dancers without work are now resorting

to oral sex in sleazy bars in the outskirts of Mumbai to earn money. Another report stated that the mujra places, which had earlier

closed down, have received a boost. The worst was the news story of a young journalist who visited the DCM, claiming to be a bar dancer,

photographer in toe, with the intention of trapping him in a compromising position. But the plot boomeranged and the journalist and the

photographer were arrested. Later the DCM issued a statement that the girl was a mere pawn used by the editor and the same thing happens

to the bar dancers. One wonders whether he will now ban women from working as journalists in newspapers because there is likelihood of

exploitation!

So, all in all, during the last few months, the city is abuzz with never a dull moment.

A peep into reality

Since most activists on both sides of the divide had never visited a bar, to dispel some of the prevailing myths, some women's groups

were keen to conduct a study. The Women's Studies Centre of the S.N.D.T. University, Mumbai, also got involved. Through the intervention

of the Bar Girls' Union, the bar owners were contacted and the dance bar doors were opened to the research team. Time was running out as

the cabinet had cleared the Ordinance and had sent it to the Governor for approval.

50 percent of the women who were interviewed were from backward castes, marginalized communities and notified tribes of Madhya Pradesh...

50 percent were illiterate and only 25 percent had studied beyond the primary level... in 60 percent of the cases women were the sole

breadwinners of their families.

The Governor did not sign the Ordinance on the expected date and the time factor swung in favour of the anti-ban lobby. On June 13, 2005,

the Research Unit of S.N.D.T. and women's groups held a press conference and released a preliminary report. The study helped to bring

into question many of the popular myths regarding bar dancers.

Contrary to the official statement that more than 75 percent of the dancers are Bangladeshis and constitute a security risk, the sample

study revealed that only 2 of the 153 girls who were interviewed were outsiders - they were Nepalis. Around 20 percent of the women were

either from Mumbai or came from poverty stricken districts of Maharashtra. 50 percent of the women who were interviewed were from

backward castes, marginalized communities and notified tribes of Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan - Bedia, Chari, Rajnat,

Dhanawat, etc. The literacy levels were low - 50 percent were illiterate and only 25 percent had studied beyond the primary level. They

had no training in any other skills.

In 60 percent of the cases women were the sole breadwinners of their families. Their average monthly income ranged from Rs.5000 to

Rs.35,000. None of them owned property or even a dwelling house. They lived in rented tenements. Out of their earnings, they spent a

sizeable amount on costumes, makeup, travel and rent. The rest was spent on children's education, for the marriage expenses of their

sisters, and for medical expenses of ailing parents. Most sent some money back to their families in their villages. All the mothers

chased a dream - to send their children to English medium schools.

Though the sample size is small, the random survey served to refute the premise that bars are in fact brothels where minors are

trafficked. The average age of the women who were interviewed was 21 - 25. But 55 percent of the women had entered the bars when they

were minors, between the ages of 15-18. This is not surprising as most girls from disadvantaged socio-economic groups either enter the

job market or are married off by this age. The dancers came to the bars through contacts with other women from their community or friends

who were working in bars. They were in the profession out of choice, though some admitted that they did not enjoy dancing.

Extracts from the Amendments to the Bombay Police Act, 1951 to ban Dance bars

AND WHEREAS the Government has received several complaints regarding the manner of holding such dance performances ;

AND WHEREAS the Government considers that such performance of dances in eating houses, permit rooms or beer bars are derogatory to the

dignity of women and are likely to deprave, corrupt or injure the public morality or morals;

AND WHEREAS the Government considers it expedient to prohibit such holding of performance of dances in eating houses, permit rooms or

beer bars;

AND WHEREAS the Government considers it expedient to further amend the Bombay Police Act 1951, for the purposes aforesaid ; it is hereby

enacted in the Fifty sixth Year of the Republic of India as follows :-

Sec 1 This Act may be called the Bombay Police (Amendment) Act, 2005

Sec 2 : After Section 33 of the Bombay Police Act, 1951, the following sections shall be inserted, namely :

Section 33A

(1)(a) holding of a performance of dance of any kind or type in an eating house, permit room or beer bar is prohibited

(1)(b) all performance licences issued under the aforesaid rules by Commissioner of Police District Magistrate or any other officer, as

the case may be (being the Licensing Authority) to hold dance performance of any kind or type in an eating house, permit room or beer bar

shall stand cancelled

(2) Punishment for violaton imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years or with fine upto to Rs.2 lakhs or both. Not less than

three months and fine not less than Rs.50,000/-

Section 33B

Nothing in section 33A shall apply to the holding of a dance performance in a drama theatre, cinema theatre and auditorium or sport club

or gymkhana where entry is restricted to its members only or a three starred or above hotel or in any other establishment or class of

establishment, which having regarding to (a) the tourism activities in the State or (b) cultural activities, the State Government may by

special or general order, specify in this behalf.

The dancers stated that they had a greater security in the bars due to the support network among the dancers as well as the protection

provided by the owners. Usually each bar had 30-60 dancers. The drivers of taxis and auto rickshaws that were used to take them to work

and back were regulars and hence they did not feel insecure while travelling home late at night. The only thing they feared was the

police raid and the sexual exploitation by the guardians of the law!

The positive outcome of the entire controversy and the media glare has brought the bar girl out of her closeted existence. It has made

the bars more transparent and accessible for women activists and researchers. But several lurking doubts continue to haunt me.

Due to the ban the lot of the bar owners and the bar girls has been thrown together by the political developments and

there is

no other choice for both but to struggle for their survival together. Today the interests of bar girls and the bar owners are common. But

what will happen tomorrow if the Bar Girls' Union takes up questions which are uncomfortable for the bar owners? Can the Union operate

without the support and approval of bar owners? Does it have the strength to negotiate better working conditions for the bar dancer?

And what about the women's groups who are opposing the ban? Has our intervention strengthened the bar owners and wrapped them with a

cloak of legitimacy? Initially women's groups resisted, but it had become obvious that if the women's groups wanted to play any role at

all, they would have to deal with the bar owners. This realization dawned on the anti-ban groups very late. Only within an atmosphere of

mutual trust was it possible to enter the bars and conduct the study.

Personally, the entire experience has helped me to gain greater insights into the lives of women who live at the margins and form the

underbelly of the city's nightlife. It has also helped me to question my own notions of morality and to encounter the sleazy world of

sexual erotica. I have become astutely aware of the realities of a bar dancer and the various levels of power politics that is played out

upon her body.

But what have been the gains for the bar dancer? Were the underground existence and the invisibility within which she negotiated her

sexuality, morality, and economics more comfortable to her? Has the exposure made her even more vulnerable than the condition she was

living in, before all of us entered her life? I do not know.

Acknowledgement: I thank Varsha Kale, President of the Bharatiya Bar Girls Union and the bar dancers for the insights into this

issue. However, the views expressed here are mine alone.

Flavia Agnes

Flavia Agnes is a lawyer and women's rights activist. She is also the founder member of Majlis, a legal and cultural

resource centre based in Mumbai.

-

This issue of Manushi: Table of Contents

![]() Hypocritical morality

Hypocritical morality

Is the morality of bar dancing judged objectively, using criteria that are applied to other professions too?

Or is this simply a political tussle that is conveniently couched in the language of morals?

Flavia Agnes

recounts the developments and events leading up to the ban in Maharashtra.

On July 21, 2005, the Bill to ban the dance bars in Maharashtra was passed unanimously at the end of a 'marathon debate'. It was a sad

day for some of us paltry group of women activists, who had supported the bar dancers and opposed the ban. We were far outnumbered by the

pro-ban group, the 'Dance Bar Virodhi Manch' who had submitted 150,000 signatures to the Maharashtra state assembly insisting on the

closure of dance bars. The ban came into effect from August 15.

•

Moral police, not policing

•

Who defines obscenity?

•

Moral bathwater, dance-bar babes

![]() Legislators opined that western, English and Tamil films are all obscene. But they did not say a word about Hindi and Marathi films

presumably because these belong to "amchi Mumbai".

Legislators opined that western, English and Tamil films are all obscene. But they did not say a word about Hindi and Marathi films

presumably because these belong to "amchi Mumbai".

The traders, the sailors, the dockworkers, the construction labourers and the mill hands - all needed to be 'entertained'. So the

government marked areas for entertainment called 'play houses' which are referred to in the local parlance even today as 'pilay house'

areas. Folk theatre, dance and music performances and, later, silent movie theatres all grew around the 'play houses' and so did the sex

trade. Hence Kamathipura - a name which denoted the dwelling place of a community of construction labourers, the Kamtis of Andhra

Pradesh, later came to signal the sex trade or 'red light' district of the old Bombay city. Within the red light district there were also

places for performance of traditional and classical dance and music, and the mujra houses.

The traders, the sailors, the dockworkers, the construction labourers and the mill hands - all needed to be 'entertained'. So the

government marked areas for entertainment called 'play houses' which are referred to in the local parlance even today as 'pilay house'

areas. Folk theatre, dance and music performances and, later, silent movie theatres all grew around the 'play houses' and so did the sex

trade. Hence Kamathipura - a name which denoted the dwelling place of a community of construction labourers, the Kamtis of Andhra

Pradesh, later came to signal the sex trade or 'red light' district of the old Bombay city. Within the red light district there were also

places for performance of traditional and classical dance and music, and the mujra houses.

![]() As the demand grew, women from traditional dancing / performance communities of different parts of

India, who were facing a decline in patronage of their age-old profession, flocked to Mumbai (and later to the smaller cities) to work in

dance bars. These women from traditional communities have been victims of the conflicting forces of modernization. Women are the primary

breadwinners in these communities. But after the Zamindari system introduced by the British was abolished, they lost their zamindar

patrons and were reduced to penury. Even the few developmental schemes and welfare policies of the government bypassed many of these

communities. From their villages, many moved to cities, towns and along national highways in search of a livelihood. The dance bars

provided women from these communities an opportunity to adapt their strategies to suit the demands of the new economy.

As the demand grew, women from traditional dancing / performance communities of different parts of

India, who were facing a decline in patronage of their age-old profession, flocked to Mumbai (and later to the smaller cities) to work in

dance bars. These women from traditional communities have been victims of the conflicting forces of modernization. Women are the primary

breadwinners in these communities. But after the Zamindari system introduced by the British was abolished, they lost their zamindar

patrons and were reduced to penury. Even the few developmental schemes and welfare policies of the government bypassed many of these

communities. From their villages, many moved to cities, towns and along national highways in search of a livelihood. The dance bars

provided women from these communities an opportunity to adapt their strategies to suit the demands of the new economy.

![]() State revenues and raids

State revenues and raids

![]() Under Congress rule

Under Congress rule

![]() Rather ironically, just around the time when the DCM's announcement regarding the dance bar ban was making headlines, the Nagpur Bench of

the Bombay High Court gave a ruling on the issue of obscenity in dance bars. While according to the Home Minister the dances in bars are

obscene and have a morally corrupting influence on society, the High Court held that dances in bars do not come within the ambit of S.294

of the IPC.

Rather ironically, just around the time when the DCM's announcement regarding the dance bar ban was making headlines, the Nagpur Bench of

the Bombay High Court gave a ruling on the issue of obscenity in dance bars. While according to the Home Minister the dances in bars are

obscene and have a morally corrupting influence on society, the High Court held that dances in bars do not come within the ambit of S.294

of the IPC.

While dismissing the appeal filed by the State, the Bombay High Court held as follows: "An adult person, who pays and attends a cabaret

show in a hotel runs the risk of being annoyed by the obscenity ... " Interestingly, prior to the raid, the policemen had sat through the

performance and enjoyed the same. Only when the show was complete did they venture to arrest the dancer. The Court posed a relevant

question - when and how was annoyance caused to the police, who had gone in to witness a cabaret performance? Regarding notions of

morality and obscenity, the judge commented: "A cabaret performance may or may not be obscene according to the time, place, circumstances

and the age, tastes and attitude of the people before whom such a dance is performed."

While dismissing the appeal filed by the State, the Bombay High Court held as follows: "An adult person, who pays and attends a cabaret

show in a hotel runs the risk of being annoyed by the obscenity ... " Interestingly, prior to the raid, the policemen had sat through the

performance and enjoyed the same. Only when the show was complete did they venture to arrest the dancer. The Court posed a relevant

question - when and how was annoyance caused to the police, who had gone in to witness a cabaret performance? Regarding notions of

morality and obscenity, the judge commented: "A cabaret performance may or may not be obscene according to the time, place, circumstances

and the age, tastes and attitude of the people before whom such a dance is performed."

![]() Opposition to dance bars

Opposition to dance bars

![]() While the ban will affect the bar dancer from the ordinary dhabas run by Punjabis and Sardars and the South Indian eateries run by the

Shetty community, it will not affect the higher classes of dancers who perform in hotels which hold three or more "stars", or clubs and

gymkhanas. Can the State impose arbitrary and varying standards of vulgarity, indecency and obscenity for different sections of society

or classes of people? If an 'item number' of a Hindi film can be screened in public theatres, then an imitation of the same cannot be

termed as 'vulgar'. The bar dancers imitate what they see in Indian films, television serials, fashion shows and advertisements. All

these industries have used women's bodies for commercial gain. There is sexual exploitation of women in these and many other industries.

But no one has ever suggested that you close down these industries because there is sexual exploitation of women!

While the ban will affect the bar dancer from the ordinary dhabas run by Punjabis and Sardars and the South Indian eateries run by the

Shetty community, it will not affect the higher classes of dancers who perform in hotels which hold three or more "stars", or clubs and

gymkhanas. Can the State impose arbitrary and varying standards of vulgarity, indecency and obscenity for different sections of society

or classes of people? If an 'item number' of a Hindi film can be screened in public theatres, then an imitation of the same cannot be

termed as 'vulgar'. The bar dancers imitate what they see in Indian films, television serials, fashion shows and advertisements. All

these industries have used women's bodies for commercial gain. There is sexual exploitation of women in these and many other industries.

But no one has ever suggested that you close down these industries because there is sexual exploitation of women!

![]() The research team acted quickly and interviewed 153 dancers from 15 randomly selected bars across the city. The bars had been selected

keeping in view the cultural and socio-economic diversity of the city. The women were interviewed within the bars, during their rest

intervals. This methodology also provided an opportunity to observe the working conditions and extent of sexual exploitation within the

bars.

The research team acted quickly and interviewed 153 dancers from 15 randomly selected bars across the city. The bars had been selected

keeping in view the cultural and socio-economic diversity of the city. The women were interviewed within the bars, during their rest

intervals. This methodology also provided an opportunity to observe the working conditions and extent of sexual exploitation within the

bars.

Manushi, Issue 149

(published October 2005 in India Together)

-

Feedback:

Tell us what you think of this article