Weaving a new life

Along with other artisan communities, the weavers of these villages began to feel that their skills were no longer of any use. As the village economy broke up, they sold their looms. They also felt that the age of the unorganised handloom sector was at an end because they could no longer sell their goods in markets accessible to them at competitive prices. Increasingly, women were forced to seek employment in addition to their traditional responsibilities to their households and families. Women sought employment in neighbouring factories or in nearby Delhi as unskilled labourers. Their status, however, is unchanged, as in much of rural Uttar Pradesh; they typically remain subjugated by their husbands and sons, and are discouraged from educating themselves.

AN NGO INITIATIVE: In response to this bleak situation, the Indian Institute of Natural Resources Management (IINREM), a non-government organization formed in 1991, decided to take action. The aim was two-fold: to organize the weavers of five villages of western Uttar Pradesh that were identified by local Government officials as particularly demoralised and deracinated, and to provide women in the villages with marketable skills. Members of IINREM reviewed the situation and developed a strategy to create real and lasting changes in Surajpur, one of the chosen villages.

Surajpur's cooperative society empowers women.

May 1999: The settlements of the Trans-Yamuna area in Uttar Pradesh near New Delhi represent the upheaval and tumult of societies undergoing transformation from an entirely rural/agrarian environment to an urban one. With changes in land use, agrarian folk are often deprived of their traditional occupation, livelihood and land. They are now expected to become entrepreneurs and understand the needs of global markets. Most of these people are not even literate. Migration to city slums and employment as unskilled hard labourers often seem to be the only option. For the defiant among them, drunkenness, petty and sometimes organized crime is always close at hand.

A hand-woven durree made of jute and cotton by the women of

Surajpur's

successful cooperative

A hand-woven durree made of jute and cotton by the women of

Surajpur's

successful cooperative

LINKING MARKET DEMAND WITH SKILL ENHANCEMENT: To strengthen and structure the process of capacity building, training projects funded by government agencies were organized and about 150 women were trained over a period of two years. A large number of them were from the families of traditional weavers and eventually made up the core of the cooperative society, the Mahila Bunkar Sahakari Samiti

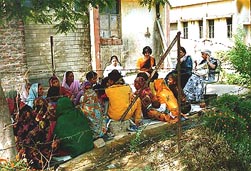

Members of the

cooperative society at a meeting

Members of the

cooperative society at a meeting

In setting up a viable business for the group of women weavers, identification of markets was a necessary step. IINREM approached Fabindia, a retailing house that was seasoned in dealing with village weavers, had a devoted clientele, and had the potential for expansion. Fabindia additionally has a very strong nationwide presence in the handloom sector. Fabindia helped the Surajpur weavers directly by placing orders with them for their goods and also indirectly, by lending credibility to their work. As a consequence Surajpur now has a reputation for weaving excellence. The training of the women was conducted with this goal in mind and the orders placed by Fabindia have become their mainstay.

The road to this goal was rough. Both the weavers and IINREM members struggled to bring down costs, raise weaving standards, meet production deadlines and promote the products. Weavers had to be schooled to understand the demand for new products and to accept the market requirements of quality assurance, competitive prices and timely delivery. Several weavers dropped out of the program because these concepts clashed with the pace of rural life. Other difficulties lay ahead for those who persevered. For instance, in the early days of the cooperative, there was considerable difficulty on the part of members in understanding that their centre was not a profit making undertaking for the promoters. Even with office bearers elected from amongst the women weavers, most members saw the organization as a factory owned by the promoters. It became clear that the weavers had to be brought face-to-face with their customers to realize their role in maintaining and running the cooperative.

As the cooperative grew, new markets and approaches had to be explored to accomodate the growing numbers of weavers. The excess materials that the cooperative produced were sold at fairs, giving the women an opportunity to see for themselves how transactions took place. Feedback from the customers made them think of the worth of their products and of introducing innovations in their work. They learned more about collective and individual responsibility and grew more confident. Interaction with cooperatives from other regions also helped the Surajpur women enhance their understanding of a cooperative setup.

Through one season of such participation, the cooperative came into contact with designers, other manufacturers and traders. In March 1996 IINREM contacted an export house named ALPS, which helped the cooperative identify appropriate products for export. They trained the weavers, supplied them with raw material and proposed a "buy back" system for their eco-friendly products. By linking demand for specific products with training and skill enhancement, IINREM encouraged interaction between the weavers and the exporters, thereby ensuring fair earnings for the weavers and satisfaction for the buyer. Presently, some 12 looms and 10 women are engaged in winding and warping (a form of yarn arrangement) for ALPS. This connection with the export house has brought in new technology and encouraged the use of natural dyes in response to demands from the international market.

Sound planning and market-oriented approaches have made weaving the mainstay of Surajpur's employment, and the village has acquired a reputation for skilled work.

Sound planning and market-oriented approaches have made weaving the mainstay of Surajpur's employment, and the village has acquired a reputation for skilled work.

FAMILY WELFARE Apart from the purely economic pre-occupation, the women have received health check-ups, eye care and post natal care. They have been encouraged to save some portion of their earnings in post office bank accounts. Other social workers have been invited to interact with the cooperative members, who are very gradually coming to see themselves as part of an integrated group. The cooperative is now 4 years old and has achieved a considerable amount in this short time. However, family and village pressures continue to be very strong and are such that the women often give up and revert to their previous role of near-bondage. While efforts made by the cooperative have resulted in greatly improved savings, the women need constant reassurance that they, too, have the right to eat better and improve their physical well being.

Clearly, the existence of the cooperative depends entirely on its ability to generate income. This is the main attraction as the women can now earn more than the minimum (prescribed) daily wage. Their self esteem, self reliance and capacity to take on responsibility has grown although they are not yet strong enough to withstand societal pressures. Social set-ups demand total obedience from the woman towards all the male members of the family, including her sons. For this reason, some women do not reveal their entire incomes to the men as most of their finances would go to providing liquor or cigarettes and would be diverted from essentials. In fact, the process of empowerment needs to be somewhat low key and subtle so that the transition to a more equitable family situation is achieved without antagonism.

IINREM is optimistic that it can take on larger training programmes in the same area. The cooperative may expand its membership if there are projects that train women in compatible skills. This is likely to become clearer in the next two years. With a view to improving the conditions of the present Cooperative and strengthening its work, IINREM hopes to establish accessible health facilities for the women and their families. At the same time, identifying new markets and products for the cooperative remains an on-going effort.

Tara Acharya

May 1999