Each year, 9 August is celebrated globally as the International Day Of The World's Indigenous Peoples. There are over 476 million indigenous peoples living in 90 countries across the world, accounting for 6.2 per cent of the global population, according to the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. India is home to one-third of the world’s indigenous population, over 104 million tribal people were counted in Census 2011, and that figure is growing as the Indian population grows.

An important aspect of the changing lives of indigenous people is the rapid loss of many of their languages. Although indigenous peoples make up less than six per cent of the global population, they speak more than 4000 languages. Indigenous languages are central to the identity and an expression of the self-determination of indigenous peoples. But many of these languages are now at risk of being lost, as the few remaining speakers are quite aged. "Every fortnight, at least one indigenous language vanishes from the earth," said Tijjani Muhammad-Bande, President of the UN General Assembly's department of Economic and Social Affairs. Each lost language takes away a unique cultural system and worldview forever.

The situation in India is similar. "Around 250 languages in India have already died over the past 60 years," says Ganesh Devy, a linguistic researcher who conducted the People's Linguistic Survey of India in 2013. There are 600 potentially endangered languages in the country and each dead language takes away a unique culture system, he added. According to a research study conducted in 2019, five languages spoken in the Himalayan region were only spoken by fewer than 100 people -- a point at which a language is considered effectively extinct.

"Most indigenous languages do not have a written script," points out Laxmidhar Singh, a Ho Adivasi activist based in Bhubaneswar. The loss of speakers, not only to age but to migration and adoption of other languages to interact with others, threatens to wipe them out. In the absence of urgent measures, we may lose them, and along with them the rich knowledge repository of indigenous people. This has particular implications for global ecological issues like biodiversity loss, climate change and even food secuity -- since nearly 80 per cent of the Earth's biodiversity is found in indigenous homelands.

But this is not inevitable. With some effort, it is possible to preserve, and even revive indigenous languages. The example of the Asur adivasis in Jharkhand is noteworthy - in collaboration with local civil societies, they have been reviving their language and historical identity.

The Asur Adivasis

The Asur tribe are an Austro-Asiatic ethnic group, and are classified as one of the eight particularly vulnerably tribal groups residing in the hilly terrain of the Netarhat plateau covering Latehar, Gumla and Lohardaga districts in Jharkhand. The total population of the tribe is around 28,000 in the state, according to Census 2011. In addition, there are smaller groups of Asur in Assam, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, West Bengal, Odisha and Tripura. They speak the Asuri language which features in the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural organisation's list of definitely endangered languages.

"Only around 8000 Asur tribals can speak their language," said Rohit Kumar, project coordinator, Bikash Bharti, a non-profit working with the Adivasi communities in Jharkhand. Asuri exists only as a spoken language and lacks written script. Also poor institutional support and historical misrepresentation are some of the main reasons for its distinction as an endangered language, he pointed out.

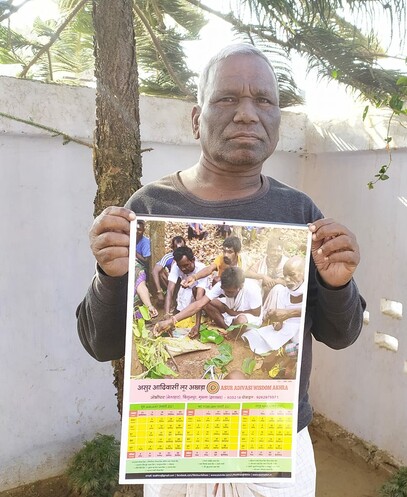

Picture: An Asur calendar, published by the

Asur Adivasi Wisdom Akhra in Gumla district.

Asur tribal rights activists and local civil societies are coming forward to preserve their indigenous language. Some are printing simple everyday material, like calendars, in the language using other scripts (shown in picture). A more substantial initiative is organising Asur mobile radio programmes in remote areas of Latehar district. The programme on average spans generally between 30-45 minutes duration which disseminates information related to global incidents, local news, songs, covid-responsible behaviour, basic health care and various pro-poor government schemes in the Asuri language. These programmes are recorded first and then transmitted to flash drives and eventually played through mobile and sound boxes in weekly markets, bus stops and other community gathering places.

"In this way, we are able to reduce the radio broadcasting cost," said Sushma Asur who has been instrumental in preserving the Asuri language. "We are also encouraging Asur youth to write poems and elderly to narrate their experience in their language," she added. Most of the content for mobile radio programmes is from the community members themselves, while volunteers, tribal rights activists and civil societies provide other crucial information.

Picture: Manita Asur and Sushma Asur recording songs.

Picture: Manita Asur and Sushma Asur recording songs.

"This is a first-of-its-kind campaign to revive a dying Adivasi language in Jharkhand," said Vandana Tete, who coordinates the Asur mobile radio programme and also serves as the general secretary of Jharkhand Bhasha Sahitya Sanskriti Akhra (JBSSA). Since 2003, JBSSA in collaboration with the Pyara Kerketta Foundation has been preserving tribal culture, traditions and ancestral wisdom. "The mobile radio programme is an important effort to popularise the Asuri language especially among the younger generations who are often influenced by the dominant mainstream languages," she explained.

Article 13 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples states that indigenous peoples have the right to revitalise, use, develop and transmit to future generations their languages, oral traditions, writing systems and literature. Similarly, Article 14 and 16 uphold indigenous peoples' rights to establish their educational systems and media in their own languages.

The Asur adivasi people are breathing life into these articles in Jharkhand, and demonstrating simple yet pragmatic ways to safeguard their indigenous language. The government, development institutions, media agencies and researchers could easily collaborate with other Adivasi communities to repeat a lot of this, and preserve, revitalise and promote more endangered languages before they are lost forever.