In November 2013, 35-year-old Rakhi Bhadra who worked as a domestic maid in Delhi, was reportedly tortured and murdered by Jagriti Singh, the dentist wife of the BSP MLA Dhananjay Singh. According to the autopsy report, the deceased 35-year-old Rakhi Bhadra, a native of West Bengal, had injury marks all over her body, from head to toe. Subsequently, she succumbed to the injuries inflicted on her by beating, due to "excessive bleeding". The post-mortem that took nearly four-and-a-half hours was conducted at Sucheta Kriplani Hospital.

Jagriti reportedly confessed to have beaten up Rakhi, who was found dead in their apartment in Chanakya Puri in Delhi. Rakhi had allegedly been burnt with hot iron rods and kicked repeatedly. She had burn marks all over her body and injuries on the chest, stomach, arms and legs. Her son, Shehzan, 21, reportedly fled from Chanakyapuri in Delhi for fear of his life and even refused to take custody of his mother's body.

Earlier in July 2013, a Delhi court rejected the bail plea of a woman who was arrested for allegedly torturing and illegally confining her teenage domestic help in her house in Vasant Kunj. Metropolitan Magistrate Gomati Manocha dismissed the bail plea of accused 50-year-old Vandana Dhir and directed the jail authorities to provide psycho-analytical therapy and counselling to her.

None of these cases is a one-off aberration. Cases of abuse of domestic helpers occur with disturbing regularity, as sustained media research over any reasonable span of time would reveal. A 15-year-old domestic help continuously tortured by her woman employer, was taken cognizance of by the Delhi government last October. Calling the incident "horrible, barbaric," the then Minister of Women and Child Development Kiran Walia said the government would bear the medical expenses of the victim, who was rescued from her employer's house in Vasant Kunj and admitted to hospital with knife injuries.

Delhi has around 2300 domestic work agencies. Each agency charges Rs 25000 from a client and even takes away the monthly salary of the domestic servant, girl or boy. The children have no clue to whether their families are receiving the money or not.

Jyotsna Khatry began her career as a filmmaker with ANHAD, a non profit organization where her role was to interview, conceptualize and edit films on victims of the Gujarat carnage and on Anhad's work in livelihoods and education in Kashmir. She later assisted Rakesh Sharma on a number of projects - the state of rehabilitation of Gujarat carnage victims, 2002, the emergence of the Hindu right wing in the country, and farmer suicides in Gujarat. She won a National level award for the L.I.V.E campaign, a Times of India initiative, for her short film.

In keeping with the rulings in the Juvenile Justice Act, the names of the children in the film have been changed to conceal their identity. The viewer is shocked to learn that Delhi has around 2300 domestic work agencies. Each agency charges Rs.25,000 from a client and even takes away the monthly salary of the domestic servant, girl or boy. The children have no clue to whether their families are receiving the money or not. There is no specific law to tackle child trafficking for domestic servitude in the country, which makes the problem more acute and difficult to solve.

What motivated Jyotsna to make this film? Says the director, "I was a film student at SAE Bangalore in 2007 when I read the story by Neha Dixit in Tehelka called The Nowhere Children. It talked about the different purposes for which kids were trafficked. I had no idea that kids were trafficked for domestic servitude too. That's when I decided to find these kids and do a film with them."

Khatry lived in Bangalore till 2011 but after trying to find some of these children and talking to a lot of child rights activists, she realized that Delhi would be the best place to make this film. She moved to Delhi in 2011. "I had no clue about how funds could be raised. I started looking for a job and found one with the Times of India Foundation and funded the film with my savings. By the time the shoot got over, I had to leave the job to be able to sit with an editor, but by then I had no money left. So friends started giving us money for editing. We used an online platform called Orangestreet.in where we uploaded the trailer of the film and even people who did not know us at all gave us funds to finish the film," she reminisces.

The film presents some really sad but nevertheless typical instances of children being employed and abused by households. Vinay, 13, works as a domestic help for eight years. He belongs to Barabanki in UP from a village called Dube Ka Purwa. He says he would be beaten and bashed up mercilessly but he internalised the beating as something that was 'natural' between a master and servant. He subsequently returned home with the help of one of the many NGOs Khatry interacted with during her research for this film.

Sabina, a Bengali girl, says she had gone to Chapra Market in December with Rocky, her boyfriend. "He gave me something sweet to eat and I really do not recollect clearly how I landed with the agent who placed me as a domestic help in a Delhi home. She finally managed to escape.

But not all are fortunate enough to be able to flee. Savitri, from Lodhma village in Jharkhand has been missing since 2002. The last her family heard of her was when they got a letter from her stating that her salary was Rs. 2050 per month. She wrote that Sameena Placement Agency (Registration No.1112001) had asked for her transfer certificate and caste certificate which the father furnished, but the girl has been untraceable since.

The father of a missing girl from Sundarkhali village in the Sundarbans in West Bengal says that he was deceived by an agent in the village who had promised that the girl would be placed in his sister's home in Delhi. The mother of another girl from Sandeshkhali, Sundarbans in West Bengal complains that she was not even allowed to speak to her daughter working in a home at Sangam Vihar. Many months later, the girl was brought back to her family. Another girl was brought back by her brother with the help of the police and is now reunited with her family.

Girls rescued from trafficking and bondage at an Assam home.

Picture Courtesy: Jyotsna Khatry.

The film also takes a close look at the notorious case that made national headlines. It is about a teenaged girl who was employed as a domestic servant in an upper-class Delhi home, the employers being a doctor-couple. They locked her from outside and went away for a holiday abroad without giving her enough food and even the water supply dried up. She was finally rescued by a fellow-maid who came in part-time. This maid informed the police, the girl was rescued and the couple has been arrested. The camera interviews this girl but discreetly keeps away from focussing on the full face and figure of the girls to protect their privacy and to refrain from any sensationalization of the subject.

The director uses a hidden camera while interviewing Rihaan Khan, who runs an agency at Tughlakabad Extension. He says they get a one-time commission of Rs.25,000 while placing the servants, adding that most of the little girls and boys do not know their correct age.

The camera then moves to a high-end shopping mall, asking questions of mothers employing nannies for their children. A foreigner lady says "Bengalis are good nannies and some of us take them along to England with us. They all come from West Bengal." In reality though, these workers come from all over the country, though mainly from the eastern regions . Jharkhand, U.P., West Bengal and Uttarakhand. Assam and the neighbouring states are also suppliers of such labour.

One thing that the film has been unable to do is to have an open talk with the employers of such children on the whole issue of trafficking for domestic servitude. "Even employers are being tricked by the agents and oblivious to the fact that these people are culprits. Unfortunately, however, no employer was ready to talk to us and so, we had to conceal the real subject and interview them at a very superficial level, which hasn't worked very well for the film," laments Jyotsna.

"We did not have too many obstacles because everybody helped us in every way, be it the NGOs, Delhi Police, the subjects and even the people who worked on this film. The biggest obstacle while making this film was my own attitude change on how footage hungry I had become but one of the subjects helped me tackle that," she sums up.

Fortunately, there are many active NGOs who are totally committed to the rescue and rehabilitation of these children. Shots show a group of rescued girls being sworn in before training at the Kishori Niketan Rehabilitation Home in Ranchi, Jharkhand. Another shot shows some of the rescued girls singing and dancing at the Mahila Sikshan Kendra in Jhansi, Jharkhand.

Jyotsna Khatry and her team make a special mention of various organisations and individuals for their contributions to the cause and her film: Kishalay Bhattacharjee; Shakti Vahini, Delhi; Kamla Market Police Station; Don Bosco; HAQ Centre for Child Rights in Delhi; Sister Seli . Sisters of Mary Immaculate Krishnanagar; Childline, Sandeshkhali; Dhangagia Social Welfare Society, Sandeshkhali; Save the Children; Bharatiya Kisan Sangh and the Jharkhand Mahila Samakhya Society. "We got some additional footage from JMSS, Shakti Vahini and Tanveer Ahmed of NDTV, Delhi," she adds.

The film very importantly draws attention to the fact that 'trafficking' is a very wide term; it is a social crime that is not confined to girls alone but

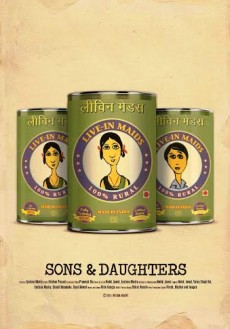

includes boys. It also exposes that trafficking is not exclusive to the sex trade. Therefore the apt name, Sons and Daughters.