How does the Indian city differ from the village? In a 1931 speech, Mahatma Gandhi said: “Princes will come and princes will go, empires will come and empires will go, but this India living in her villages will remain as it is.”

The city, it seems, does not.

In Girish Karnad’s ‘Boiled Beans on Toast’, the social butterfly Dolly Iyer laments to her friend, Anjana Padabidri: “My husband was posted here in Bangalore when he was in service and fondly remembered the Cantonment bungalows. The pillars, the porticos and the monkey-top windows… We come here now and bungalows! Ha!” Her hostess Anjana is resentful of the underpass coming up in front of her house. She hates the never-ending road-widening plans. “Our city corporation is run by people born and brought up in the countryside. They’ve no time for greenery and environment,” agrees Dolly.

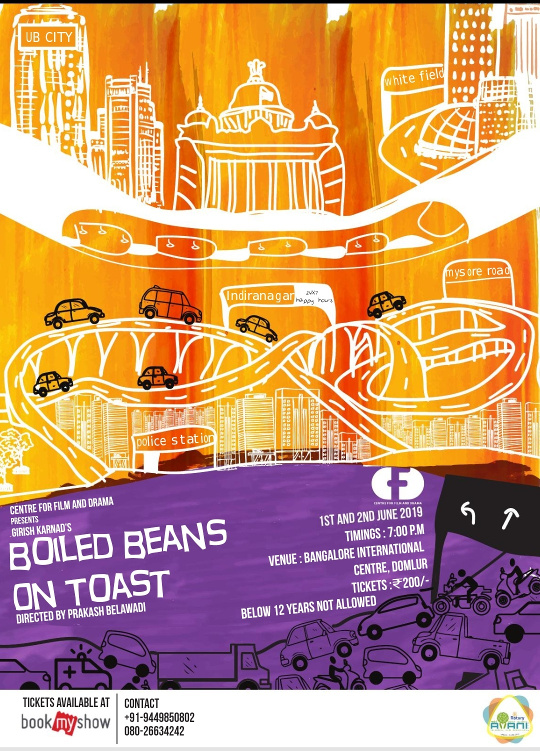

Poster of the play. Pic: CFD

Prabhakar Telang, their sudden visitor at the house, challenges this notion: “I grew up in the heart of the Western Ghats… I grew up yearning for the massive constructions of cement concrete and the towering glass-fronted skyscrapers I saw on television,” he says. Prabhakar also poses a rhetorical question to in-migrants: Who asked me to come to Bengaluru? Who asked anyone to come to Bengaluru? He also speaks for all in-migrants to the city, who see the city as a haven, a relief from the tedium of tradition in rural and small-town India.

Gandhi, in that speech, had elaborated on village folk: “They have their own culture, mode of life, and method of protecting themselves, their own village school master, their own priest, carpenter, barber, in fact everything that a village could want… these villages are self-contained, and if you want there you would find that there is a kind of agreement under which they are built.”

But what is the nature of the agreement in the community that keeps the village constant (or stagnant and suffocating, for some)? In an arrangement where its people are trapped in identities of professions – priest, carpenter, barber… where is the possibility of choice? What about oppressive social identities? Gandhi himself, in that speech, had allowed: “From these villages has, perhaps, arisen what you call the iron rule of caste. Caste has been blight on India, but it has also acted as a sort of protecting shield for these masses.”

One of India’s greatest modern intellectuals, BR Ambedkar, did not agree with this sentiment. To repeat his famous quote: “The love of the intellectual Indian for the village community is of course infinite, if not pathetic. What is a village but a sink of localism, a den of ignorance, narrow mindedness and communalism?”

During a debate in the Bombay Legislative Council, he had argued: “A population which is hidebound by caste; a population which is infected by ancient prejudices; a population which flouts equality of status and is dominated by notions of gradations in life; a population which thinks that some are high and some are low can it be expected to have the right notions even to discharge bare justice? Sir, I deny that proposition, and I submit that it is not proper to expect us to submit our life, and our liberty, and our property to the hands of these panchas.” (SA Aiyar, Feb. 2014, ToI). In the play, Karnad’s characters from the village agree with Ambedkar.

The surprise is that Karnad himself is a victim of mindless road-widening in front of his residence in JP Nagar. He fought against it, without success. Karnad has participated in agitations to save Cubbon Park, the Race Course and the city’s tree cover. His clear-eyed, unsentimental and even self-deprecatory view of the changing city, therefore, seems rare in the Indian narrative imagination, which continues to nurse the notion of ‘the village innocent’ vs ‘the city corrupt’. Karnad, disconcertingly and uncompromisingly, lets his characters speak: without comment, without judgment.

‘Boiled Beans on Toast’ is seemingly light, but loaded with nuance. The only character that is genuinely ‘of the city,’ from infancy, is Kunaal – a metaphor of the boom town, its obsession with the pursuit of personal happiness, its amorality and guiltlessness.