Primla Loomba, 91, of the National Foundation of Indian Women (NFIW), reminisced, “When various women’s groups came together in the 1980s anti-dowry movement, it was difficult because there was a lot of distrust of each other. Yet, once we got together, despite our suspicions we began to build up trust and friendship, share ideas and even criticise each other. Many women, such as Vina Mazumdar of the CWDS (Centre for Women’s Development Studies), made every effort to work together. Years later, I read in a book in the UK that the women’s movement was the most important movement in India at that time!”

Loomba’s compatriot Ranjana Ray, 85, added, “It was a broad-based movement, from 1975 onwards. Aruna Asaf Ali played a key role in drawing us together, and keeping us going. I remember a case in Delhi, among many cases we fought, when one woman was assaulted by 300 men of her ‘biradari’ (community). We took up her case and helped her fight a legal battle, which she eventually won. All those men even made a public apology!”

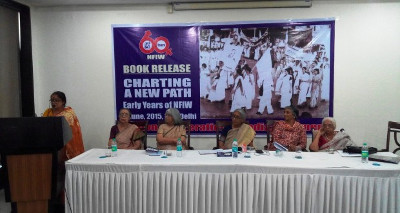

Loomba and Ray were sharing experiences and anecdotes during a discussion in the Capital recently at the release of ‘Charting a New Path: Early Years of National Federation of Indian Women’, co-authored by noted women’s rights activists, Gargi Chakravartty and Supriya Chotani.

Recently, some of the leading voices of India’s historic women’s movement, including (l-r) Lata Singh, Jyotsna Chatterji, Indu Agnihotri, Aruna Roy, Pamela Philipose and Aparna Basu gathered to share their side of the empowerment story and take stock of “how far we have come”. Pic: NFIW

The history of the movement

“India has a long history of women’s movements. My mother was active with the All India Women’s Conference (AIWC) in Kolkata well before 1947. When the NFIW was formed in 1954, some women left the AIWC and joined the NFIW. The AIWC women were disheartened but they all remained friends and colleagues and kept working amiably with each other. In 1979, when the All India Democratic Women’s Organisation (AIDWA) was set up, a number of NFIW women left and joined the AIDWA. All these organisations have continued to work together!” remarked historian Aparna Basu, who has chronicled the journey of the AIWC.

During the 1990s, the AIWC, AIDWA, CWDS, NFIW, Mahila Dakshata Samiti, Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) and Joint Women’s Program (JWP), collectively dubbed the ‘Seven Sisters’, worked on major issues, including the Uniform Civil Code and Women’s Reservation Bill, besides creating a joint presentation for the landmark Fourth World Conference on Women at Beijing in 1995.

They joined hands with autonomous feminist groups, such as Stree Sangharsh, Manushi, Action India and the play group Om Swaha, to form an anti-dowry platform called Dahej Virodhi Chetna Sangh. Diverse outfits have also continued to struggle against crimes like sexual harassment and rape, and even effected some wide-ranging changes in the law and policy and build public awareness on these inter-related concerns.

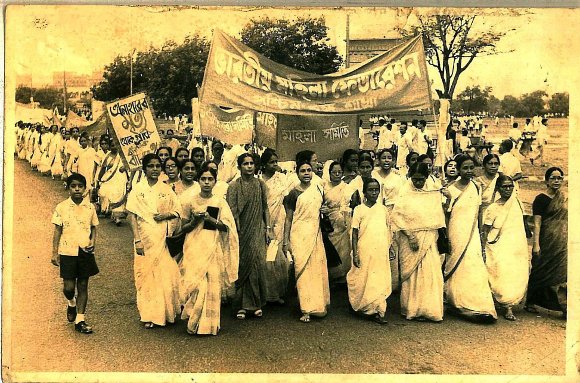

Senior journalist Pamela Philipose noted with admiration how, remarkably, decades ago, thousands of women took up cudgels against hunger and famine, led militant trade union struggles, battled colonial rule and fought for rights to education and employment.

Even as Indu Agnihotri of the CWDS and AIDWA, stated, “It is hard to build mass organisations, and women have struggled hard to build them. They represent a strong force across the country - against patriarchy, capitalism, imperialism. It is a big achievement. Social structures have to change, and this can only be possible if there are mass organisations. Nowadays when, for some people, feminism is limited to the individual, one’s own life and body, it is important to remember the wider structures.”

Not just women' rights

The first Congress of the NFIW (Calcutta, 1954) was held against the backdrop of the Cold War and military pacts, lending a certain poignancy to its declaration of “unshakeable opposition to large scale armaments, weapons of mass destruction such as hydrogen bomb, atom bomb and bacteriological weapons.”

Inspired by a vision of women across the globe uniting against imperialism, poverty and disease, leading figures such as Vidya Munsi, Ela Reid, Hajrah Begum, Anna Mascarene, Renu Chakravartty, Tara Reddy, Shanta Deb and Anasuya Gyanchand participated in meetings of the Women’s International Democratic Federation (WIDF), World Conference of Mothers (Lausanne, 1955), Afro-Asian Women’s Conference (Cairo, 1961), the anniversary of the victory of Vietnam (Ho Chi Minh city, 1977), and so on.

From Vijaywada in Andhra Pradesh, in 1957, NFIW President Pushpamayee Bose issued a rousing appeal: “We, the women of the Federation declare that we do not want war, neither here nor anywhere in the world… We demand from the Big Powers not only stoppage of all nuclear tests but cessation of all wars for the world good - we ask them not to waste their men, money and brains on war preparation but use it for the well-being of their countries”.

Many women’s organisations joined NFIW, united by the common goal of securing women’s rights. At the founding conference in 1954, 39 organisations had already joined in, yielding a membership of nearly 1.3 lakh women from peasants, workers, tribals, dalits and refugees to professionals, artists and intellectuals. Constituent organisations included Mahila Atma Rakhsa Samiti (MARS, West Bengal), Punjab Lok Istri Sabha, Nari Mangal Samiti (Orissa), and Manipur Mahila Samiti.

File picture of Rally Against Hunger by NFIW Unit of West Bengal in 1968 shows how women in India have been coming together for decades and forming groups to raise slogans and agitate to secure equal rights for women in their country and around the world. Pict: NFIW

Urmila Devi, a freedom fighter, opened the conference, saying, “The last years have seen a remarkable awakening in our women, but the progress of the few has made the backwardness of the many all the more tragic….” On the last day, some 10,000 women and 1,000 men marched through the streets of Calcutta holding banners and shouting slogans – ‘Equal pay for equal work, one maternity centre for every 10,000 people, peasant women must have right to own land, gainful employment for women, stop dowry, children need peace as flowers need sunlight….’ In fact, the 1950s were extremely active years, with concerted campaigning for social, economic and political rights, equality and justice.

The struggle continues

In the ensuing decades, hundreds of women’s organisations have led and waged common struggles, although it is important to recognise the contradictions and conflicts. While ideological diversities may be subsumed at moments they do exist beneath the surface. A glimpse of this became evident when Loomba asserted, “I disagree when people say that the question of sexuality is not important. It is extremely important…. Earlier, it was a taboo theme but now it is talked about, and it was first brought up by the women’s movement.”

JWP’s Jyotsna Chatterji voiced another concern, “The other day I was invited to speak on women’s empowerment in Mathura [a holy town in Uttar Pradesh] to grassroots women from five panchayats. When I reached the venue, women were sitting on the floor, while a man was sitting on a chair. I understood at once the structure of power in that setting. After all these years of work, where are we? What have we achieved?”

Aruna Roy, of the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS), who is the current President of NFIW, however, concluded on a hopeful note, “Let’s not be despondent. There have been many changes over the years. I live in a village in a remote part of Rajasthan, and ordinary women have been my teachers in struggle. Today, there are still many injustices, but these are being raised and discussed. Earlier, they may have gone unnoticed. We need to put together every bit of our strength, and continue the struggle.”