This year seems to be a year of basalt-hard lessons for Maharashtra. The year saw the irrigation scam, sugarcane farmers protesting for a fair price (leading to the death of two farmers) and now a ‘drought worse than 1972’ with 11,801 villages declared to be drought affected in March 2013.

If we analyse these three events in perspective, their link becomes inextricably clear. This year’s drought, though devastating, was not an unannounced calamity. It had been building up since August 2012, when more than 400 villages were declared drought-affected. The protest by sugarcane farmers was not a sudden outburst either; their discontent over fair price for sugarcane had been simmering and occasionally boiling over for the past few years. Last but not the least, the irrigation scam, though unprecedented in scale, was not a sudden revelation. Many NGOs, whistle blowers and government committees had been warning about the tip of the iceberg for several years.

![]()

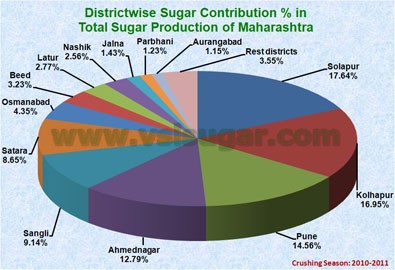

Many experts, organisations and reports like World Bank have highlighted the unjustifiably high share of sugarcane in Maharashtra's irrigation

That all these factors came together in one year is not just an unfortunate coincidence. It shows that the reasons behind the Maharashtra drought are starker than simply less rainfall. Unless these root causes are addressed, no amount of state and central assistance can banish droughts. Farmers and rural and urban poor have been suffering for too long due to the opportunistic and myopic response of the political and administrative leadership in Maharashtra to successive droughts. To understand and change this, we need to first take a long, deep look at some of the reasons sparking the water shortage:

Worst drought-affected districts have the most sugar factories

Sugarcane is one of the most water-intensive crops grown in Maharashtra, requiring ten times more water than Jowar or nut. Ironically, the regions where it is grown the most are chronically drought hit regions, which have been receiving central aid for drought proofing though the Drought Proof Area Program and other such schemes. Sugarcane area under drip irrigation in these regions is dismally low.

According to the Water Resources Department, Maharashtra, in 2009-10, of the approximate 25 lakh hectares (Ha) of irrigated area in Maharashtra, 3,97,000 Ha was under sugarcane. However, according to the Union Agricultural Ministry (which would get its data from the State Agricultural Department), area under sugarcane was 9,70,000 hectares in 2010-11 and again 10,02, 000 hectares in 2011-12.

When it was grown on 16% Irrigated area, sugarcane used 76% of all water for Irrigation. With area under sugarcane increasing, its hegemony has increased exponentially. Not only does it capture maximum water, it results in water logging, salinity and severe water pollution by sugar factories. Incidentally, Maharashtra has 209 sugar factories, the highest in any state in India.

A strong example of links between drought and sugarcane may be found in the Solapur District in the Bhima Basin, which is facing the worst of droughts today. Live storage of Ujani Dam is zero and drinking water is being taken from dead storage, even as Solapur and 400 villages depend on Ujani for drinking water. Drinking water supply has become a severe problem. Hundreds of villages and blocks have been declared drought affected. Nearly 1000 tankers have been plying, and there is a near exodus of stricken communities to urban areas.

During a meeting at the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF), officials from the Water Resource Department (WRD) claimed that of the 87 TMC (Thousand million cubic feet) live storage of Ujani, 50-60 TMC is flow irrigation to sugarcane in command, accounting for more than 60% of its live storage. The authorised use, however, is only 32 TMC! In addition, there are several sugar factories in the upstream of the Ujani dam, taking water through unauthorised lifts from the backwaters. So, actual water going to sugarcane from Ujani is estimated to be close to 80% or more. This is causing severe water scarcity in the downstream regions, creating severe drinking water crisis.

All of this diversion apparently happens with political support. Of the 30 cabinet ministers in Maharashtra, 13 ministers either own sugar factories, or a substantial share in these. The White Paper on Irrigation Projects proudly boasts that the Ujani Project irrigates 92000 hectares of Sugarcane.

Apart from Ujani, Pune region (Districts Satara, Solapur and Pune), Ahmednagar Region, Aurangabad region and Nanded region, - all of them drought-prone areas - also have a dense concentration of sugar factories, aided by irrigated sugarcane fields in the vicinity.

Sugarcane is increasing in area in drought affected Krishna and Godavari Basins too, commanding maximum share of the irrigation water. This is borne out by the table below, all figures taken from the Maharashtra Irrigation Status report 2009-10 (the latest one available).

|

Area under main crops in thousand hectares

|

|||||||||

|

Region |

Jowar |

Wheat |

Ground nut |

Harbhara |

Rice |

Oilseed |

Sugar-cane |

Cotton |

Fruits |

|

Pune |

221.43 |

191.85 |

38.68 |

52.85 |

96.96 |

61.58 |

315.97 |

5.77 |

13.80 |

|

Aurangabad |

29.38 |

33.33 |

5.07 |

12.68 |

0.08 |

2.30 |

43.30 |

27.83 |

5.48 |

Sugarcane: Lifeline of the political economy of Maharashtra

A Memorandum for Drought Relief sent to the centre from Maharashtra in 2003-04 said that Sugarcane is the “Lifeline of the agro economy of Maharashtra”. However, more than a lifeline of the agro-economy, it appears to be so for the political economy of Maharashtra. Hugely entrenched in sugar politics, the political economy is unable to take any brave and sustainable decisions when it comes to cultivating sugarcane. As experts have pointed out in the past, entire water management of Maharashtra revolves around sugarcane.

The Ujani Dam, sanctioned in 1964 for 40 Crores is still not complete, while the expenses have been pegged at nearly 2000 Crores. Even as the main canal work is incomplete, more and more lift irrigation schemes, link canals, underground tunnels are being planned on this dam, for sugarcane. Incomplete projects, with bad distribution network, which has been the hallmark of the irrigation scam, has aided sugarcane cultivation the most and has resulted in concentration of water in small ‘pockets of prosperity’ amidst drought affected zones and thirsty tail-enders.

Osmanabad collector K.M. Nagzode had written to the state sugar commissioner on 29 November 2012 that Osmanabad “had received only 50% of average rainfall, and water levels in dams are extremely low while ground water hasn’t been replenished and that since a sugar factory typically uses at least one lakh litres of water a day, it would be advisable to suspend crushing and divert the harvest to neighbouring districts”. However, no such orders were given and cane crushing went on. Osmanabad district contributes significantly to sugar production of Maharashtra, with over 25100 hectares of sugarcane, which is the only crop that gets irrigation in this district.

District Collectors have the right to reserve water for drinking in any major, medium and minor projects, when they see the need. However, even when Ujani was reaching zero live storage, such decision was not taken by the Solapur Collector.

Everybody loves a good drought

A Memorandum for drought relief sent by the Maharashtra government to the Centre does not seem to be in the public domain, but the state is reportedly seeking Rs 2500 crore for drought relief. The Memorandum for drought relief, 2003-04 shows that during every drought, we indulge in the same fire- fighting measures of resorting to the Employment Guarantee Scheme, tanker water supply, cattle camps and well-control. Once the drought passes, sugarcane is pushed again.

Currently 3 million farmers and significant number of labourers are involved in sugarcane farming, it is claimed. In reality, even if a million hectares were to be under sugarcane, how can 3 million farmers be involved in sugarcane farming when the average farm size in Maharashtra is 1.45 hectares?

We have neither been able to solve the minimum price for sugarcane lock till now. Farmers have been demanding Rs 4500 per tonne of sugarcane from sugar industries, which have agreed to only Rs 2300/ tonne. In Vidarbha, the situation is even worse with prices at Rs 1500/ tonne. The government has made it clear that it will not interfere in the issue. Many sugar industries did not even pay last year’s dues to farmers. Globally and in Indian markets, sugar prices are going down. Last November, during farmers’ protests for minimum price for sugarcane, two farmers lost their lives. This protest was the strongest in the drought hit region around Ujani Dam.

Instead of hiding behind claims of three million sugarcane farmers, politicians need to ensure that these farmers do not have to suffer the same fate time and again. With climate change, droughts have become a more frequent reality. The only way to tackle and manage droughts is to improve the resilience of the agro-economic system and water management systems in coping with droughts. Encouraging and pushing for sugarcane in chronically drought-affected areas is a poor adaptation measure and only pushes farmers deeper into the vicious cycle of uncertainty, crop failures, and hardships.

Drip Irrigation: A Band-aid solution?

The Maharashtra state government is planning to make it mandatory for sugarcane growers to use drip irrigation systems over the next three years, a move prompted by the drought. “Hence a regulation will make a big difference in the water utilization pattern in the agro-sector,” chief minister, Prithviraj Chavan said in an interview.

Measures like drip Irrigation, sprinkler irrigation, etc, though critical, are incapable of arresting the proliferation of sugarcane, a fundamentally inappropriate crop in drought prone areas. Moreover, despite the relative abundance of sugarcane and heavy subsidies for drip, sugarcane belts have stuck to flood irrigation and have not adopted drip the way Nashik region has for grapes. Of the one million hectares under sugarcane, barely 10% is under drip. Even the Union Agriculture Minister’s constituency has not shown any notable success on this front.

As sugarcane is claiming almost all of irrigation and also domestic water from dams in the drought-affected zones, villagers in Marathwada and Western Maharashtra do not have drinking water; students are missing their exams to attend to cattle at cattle shelters and hospitals have to postpone surgeries for want of water. If at all Maharashtra wants to liberate itself from the shackle of regular droughts, one of the things it must first do is break free from sugarcane, and politicians who push the mirage of sugarcane in the absence of any sustainable efforts towards improving farm livelihoods.

This drought would not have been so severe if Maharashtra had broken the shackles of sugar earlier.