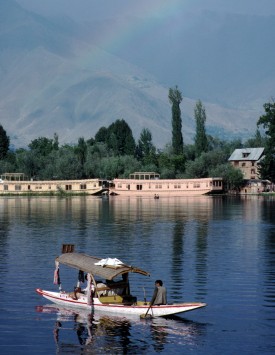

I've never been to Kashmir. I nearly went in 1987 to Srinagar; there's a guesthouse there that used to be owned by Grindlays Bank, where I was meant to stay, but then the troubles began and I stayed home. The closest I came to living in Kashmir was living in Kashmiri Gate, a neighbourhood in north Delhi where the walled city ended and the Civil Lines began. There's a cinema hall there called the Ritz, where, in the early Sixties, I saw visions of Kashmir in films like Kashmir Ki Kali. Those were the years when Bombay cinema specialized in houseboat and hill-station idylls and in these films Kashmir often stood in for Eden.

Delhi was a Jan Sangh city then; Atal Bihari Vajpayee was a promising local politician. Growing up in Kashmiri Gate, I wasn't especially political but I knew that Jan Sanghis blamed Nehru for Kashmir's disputed status. If he hadn't agreed to a plebiscite, or if he had allowed Indians from outside Kashmir to settle there, or if he hadn't made the fatal mistake of Article 370, which gave Jammu and Kashmir a special status within the Union, if he hadn't indulged Sheikh Abdullah⦠if he hadn't done all of this, we wouldn't be wrestling with secessionism and sedition in Kashmir.

For most of us who, like me, have no first-hand experience of Kashmir, the troubles in the Valley are, for the most part, a series of off-stage noises. Our governors, or more precisely, our proconsuls, sometimes become famous for making bad things worse, wars and skirmishes emblazon names like Kargil on our collective consciousness, newsworthy violence like the purging of Kashmiri Pandits from the valley or the brutalization of Kashmiri Muslims by the security forces surfaces in the newspapers and news channels, and then there are long periods of absent-mindedness when Kashmir disappears and these are the times when it's deemed to be calm or inching towards normalcy. Wise men, in these interludes, talk on television about commerce being the key to peace. Tourism's up, they say hopefully. Then the valley erupts and half-forgotten names like Hurriyat and Malik and Geelani and Farooq flicker in our heads.

This latest eruption, though, has provoked a set of unusual reactions. The enormous popular mobilization in the Valley after General Sinha, our last governor, stirred the pot by allotting a large plot of land to the Amarnath Shrine Board, and after the security forces, predictably enough, killed Kashmiri Muslims in the demonstrations that followed, has prompted mainstream journalists like Vir Sanghvi and Swaminathan Aiyar to write opinion pieces arguing that India should seriously consider letting Kashmir go.

This latest eruption, though, has provoked a set of unusual reactions. The enormous popular mobilization in the Valley after General Sinha, our last governor, stirred the pot by allotting a large plot of land to the Amarnath Shrine Board, and after the security forces, predictably enough, killed Kashmiri Muslims in the demonstrations that followed, has prompted mainstream journalists like Vir Sanghvi and Swaminathan Aiyar to write opinion pieces arguing that India should seriously consider letting Kashmir go.

Arundhati Roy, who was present at the enormous rally, made the same point more forcefully, arguing that the pro-Pakistan slogans or the distinctly Islamic idiom of the azadi vanguard, ought not to distract us from the fact that India has no right to hold the Valley's Muslims against their will. The routes by which these writers came to their conclusions are different, but the conclusion is the same: that the time has come to think the unthinkable: an azad Kashmir, or even the prospect of Kashmir becoming part of Pakistan.

Are they right? Should Indian liberals and democrats endorse self-determination for Kashmir? Or is it possible to hold another position: can a liberal oppose azadi in Kashmir in good faith? One way of exploring this is to make dhobi lists of the pros and cons of Kashmiri self-determination.

The case for self-determination is contained in the term itself. If we accept that the two hundred thousand Kashmiris who came out to protest against Indian rule, to shout for liberty, to invoke the ideal of an Islamic state, to press the case for union with Pakistan, are representative of Kashmir's Muslim population, then pressing India's claim to Kashmir with guns and bayonets is a violent negation of their collective will. It's hard for a liberal or a democrat to defend that position. No matter how violently you disagree with their ideas, or how convinced you are of Pakistani mischief and instigation, given the violence the Indian state has inflicted on Kashmiris, it's hard to argue that India is entitled to the benefit of the doubt. Kashmiri alienation is now of such long standing and the Indian state's interventions in Kashmir have been characterized by such unscrupulousness and such ruthless violence that touting India's virtues as a secular, democratic state, which Kashmiris should be glad to be part of, feels like a sick joke.

But there is a case against self-determination which needs to be made, if only to clarify the consequence of endorsing self-determination. Self-determination isn't in itself virtuous. The Tamils in Sri Lanka, led by Velupillai Prabhakaran have been fighting a civil war for decades to achieve a separate state, Tamil Eelam. Tamils have suffered violence at the hands of Sinhala chauvinists and discrimination from the Sri Lankan state, which, in the Sixties, defined itself as a hegemonically Buddhist, Sinhalese entity. I know of very few people outside of Prabhakaran's followers who want such a state to come into being. This is partly because Prabhakaran is an old-fashioned totalitarian leader and partly because a tiny, Tamil-majority statelet on a small island doesn't feel like a rousing cause.

Sri Lanka aside, we've witnessed the hideously violent unravelling of Yugoslavia in the name of self-determination. We've seen the idea of self-determination taken to its absurd extreme in the elevation of Kosovo and Ossetia, tiny enclaves, barely a million strong, into nations on the ground of ethnic or religious difference. So perhaps, as liberals, we're entitled to ask of movements of self-determination, what sort of state they aspire to. If self-determination in Kashmir is meant to create a majoritarian state on the basis of ethnicity or faith (and Arundhati Roy, in her essay, is clear that the tableau of azadi that she witnessed was substantially shaped by Islamic ideas and bound by a sense of Muslim identity), an Indian liberal might still prefer azadi because he thinks chronic, quasi-colonial state violence is worse, but at least he would acknowledge that his was a counsel of despair rather an endorsement of a freedom struggle.

Alternately, he might oppose self-determination because he thinks the Indian republic is a flawed but valuable experiment in democratic pluralism, that the Indian national movement and the nation-state it created, tried, in an unprecedented way, to build a national identity on the idea of diversity, not homogeneity. It's worth mentioning here that the Indian state has never attempted to change the demographic realities in the Valley in the way in which Israel and China have in Palestine and Tibet. The loss of Kashmir, the only Muslim-majority state in the Union, would be a) a massive setback to this pluralist project, and b) a gift to Hindu chauvinists who would cite Kashmiri secession as yet another proof of the impossibility of integrating Muslims into a non-Muslim state.

To sum up then, the Indian liberal has two options. He can support azadi in Kashmir because it is the lesser evil, knowing that azadi will almost certainly mean either a sectarian Muslim statelet or more territory for a larger sectarian state, Pakistan. Or he can endorse the Indian occupation because, in the larger scheme of things, Kashmiri Muslim suffering is collateral damage, the price that must be paid for the greater good of a pluralist India. Put like that, there's no shimmering cause to lift our liberal's spirits, just a choice between two squalid, compromised ideals.