Sahibrao Adhao paints a vivid picture of Vidarbha's debt trap. He profiles the character of the creditor, captures the pathos of the debtor. He describes the interest mechanism and how it is manipulated. Adhao brings in the local features of sahucari in the Amravati-Akola belt. Here, there is no mortgage. You just give the lender a straight deed of sale for your land. In theory, he returns the land when you pay up. In truth, he holds on to it even after you have paid up. In fact, he demands more money.

Adhao is neither an academic studying the problem nor a reporter digging into the issue. Just a small farmer who lost all his land this way and whose suicide note is meticulous in detail.

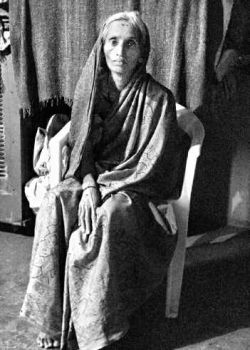

![]() In deep distress: Babytai, widow of Sahibrao Adhao, in Khirala. She is still in shock from his suicide. Adhao left behind a note that

captures the trap farmers find themselves in. (Picture by P Sainath)

In deep distress: Babytai, widow of Sahibrao Adhao, in Khirala. She is still in shock from his suicide. Adhao left behind a note that

captures the trap farmers find themselves in. (Picture by P Sainath)

"We sent a fax to Home Minister R.R. Patil," says Udhav Adhao, a relative. "So far, nothing has happened. When he was alive and made a complaint, the police arrested him, not the sahucar." That's because "he tried to prevent the latter from cutting down trees on the land grabbed from him," says Ashok, the dead man's son. "Each time my father paid off some money, the sahucar raised his demand." Adhao's widow Babytai is too distressed to say a word at their home in Khirala village, Amravati district.

"The more the banking system denies the farmer aid, the more he must go to the sahucar," says Vijay Jawandia, farm activist and leader. "People thought that after the Prime Minister's visit, they could go to their bank and get a fresh crop loan. For many, this did not happen."

In Wardha district, the suicide note of Ramkrishna Lonkar of Susandara village has grabbed attention in the local press. In it, Lonkar writes, "After the Prime Minister's visit and announcements of a fresh crop loan, I thought I could live again." In fact, he was rebuffed at every stage when he began the process of seeking that loan. The talk at the top was not matched by credit at the bottom. "I was shown no respect," he says in his note. Lonkar took his life on August 1, a month after Dr. Manmohan Singh's visit to the Vidarbha region.

"Bankers are not going to give out fresh loans even after the interest waiver," says Mr. Jawandia. "They know that farmers who could not pay back Rs.10,000 earlier cannot repay Rs.20,000 now. The more so when there is no change in the price of cotton. There is some logic in that. That's why a loan waiver is vital. It lets the farmer start with a clean slate."

Officials admit the amounts involved in a possible waiver are quite small for a State like Maharashtra. "The total advances for all these six districts is a little over Rs.1,200 crore," says one. (That figure does not include the interest.) "Tamil Nadu has waived five times that amount for its farmers." There's more. "If Rs.712 crore was the interest burden, when the advances are around Rs.1,200 crore, that's shocking. It argues the original loans were very small. The burden has been too great for too long."

"If you look at the amount taken away from farmers thanks to bad pricing and low import duties on cotton," says Mr. Jawandia, "this is a trifling sum."

Input costs, however, have not been trifling. In some estimates, Bt cotton now accounts for 50-60 per cent of the total sown area. Even after the fall in its price, it costs much more than non-Bt seed. And despite all the claims made for it, input dealers here have seen no decline in pesticide sales as a result of its use. Some claim higher sales than before. If there is any fall now, it might be due to excess rain crippling farm operations. And many farms have reported failure with Bt anyway, long before the downpour.

New 'indicators'

In the end, Adhao goes down as No. 650 in the list of farmers taking their lives since June 1, 2005. Lonkar was No. 702. Meanwhile, the official figure for suicides since 2001 has changed and confused many. One reason the total figure has shot up suddenly is that the State Government "has changed the indicators. And it has changed them with retrospective effect," says a top official. So the number now is 1,864 suicides since 2001 in the six affected districts.

In mid-2005, the State was still speaking of a total of 141 distress suicides since 2001. When challenged in court, this number changed to 524 ? State-wide. Then when the National Commission on Farmers came visiting last October, the Government told the Commission there had been over 300 in that period in a single district ? not State-wide. That was Yavatmal and the data showed that the deaths had doubled each year since 2001. Which undid the claim that the rate of suicides was "normal."

In the State Assembly in December, the Government admitted to a figure of 1,041 farmers' suicides State-wide since 2001. Today, for the same period, it accepts a figure of 1,864 ? in just six districts (Maharashtra has 35). Till late last year, it stuck to a definition of distress farm suicides that excluded very large numbers of people from its list. For instance, if a cultivator took his life but the family land was in his father's name ? this was not a "farmer's suicide." The claim was that "since there was no land in the name of the deceased, he or she was not a farmer," points out the official.

The State's list also required that each case be judged by over 40 indicators before being declared a farm suicide. It was reported at the time (The Hindu, June 25, 2005) that this kept out many deaths from the Government's list. It also meant that the bereaved families would get no compensation.

In recent months, the State has revised its approach. Now, such a tragedy in a farm household is acknowledged as a farmer's suicide even if that family member had no land in his or her name. The result: hundreds of names have been added to the list from the 2001-05 period. There have been other changes, too.

The rain lashing Vidarbha is making things much worse. A lot of those who borrowed money to buy their inputs have seen their efforts washed away. For many, it will be difficult to recover from the accumulated losses of successive seasons.