ECONOMY

The high cost of 'easy' foreign exchange

A new sop came into effect for net-foreign exchange earning businesses in

designated export zones from February 10 -- a 15-year income tax holiday.

But are the costs of the revenues foregone worth the claimed benefits of

more investment and jobs?

M Suchitra

examines the reality and does not find a rosy picture.

09 March 2006 -

It was in early 2000 that the late Murasoli Maran, the then Union Commerce and Industries Minister, went on a visit to China to garner first-hand knowledge of how a

socialist economy suddenly became the most attractive investment destination in

the world. During that trip he visited the Special Economic Zones (SEZ) in

China. Inspired by the impressive impact of these industrial enclaves on

China's economic growth, Maran introduced the concept of SEZs in the Indian economy

through the annual Export-Import (Exim) Policy in March 2000.

The effort has been to create delineated, duty-free zones with world-class

infrastructure, internationally competitive production environment and fast

track clearance system for attracting private investments, especially foreign

direct investment (FDI) for setting up export oriented units. In order to

convince the investors about the commitment of the country on SEZ scheme and to

provide them with the protection and stability of a policy regime, Parliament

passed a comprehensive legislation in May last year. When the Special Economic

Zones Act 2005 and new rules came into effect on February 10 this year, it made headlines

in the national and regional media. Newspapers and news channels quoted the

Commerce Minister Kamal Nath, "The SEZ Act and Rules will provide comfort to and

instill confidence in prospective investors." He also said that investment of

Rs.1,00,000 crores was expected to flow into the zones in the next three years

providing employment to over 5 lakh people. The mood was clearly upbeat.

(1 crore

= 10 million)

The country is now promoting the SEZ programme more vigorously than in the past.

In fact, India's experience with SEZ predates that of China. India was the first

country in Asia-Pacific region to follow the international trend of setting up

a separate zone with special incentives for earning foreign exchange through

export promotion and employment generation. The first special export processing

zone (EPZ) was set up in Kandla, Gujarat, as early as 1965. It was followed by Santacruz Electronics Export

Processing Zone which became functional in 1973. The Central government set up

five more zones in mid 1980s at Cochin (Kerala), Chennai (Tamil Nadu),

Visakhapattanam (Andhra Pradesh), Falta (West Bengal), Noida (Uttar Pradesh).

Under the new SEZ scheme, all these seven EPZs and the first private zone at

Surat which started operations in 1998 were converted to special economic zones.

China established its first zone much later in 1980.

SEZ units produce ready-made garments, gloves, spices, processed food,

electronic parts, jewellery, diamonds, etc. The companies keep their buyers'

list confidential. There are now 17 functional zones in the country, and the

New Delhi-based Board of Approval of

SEZ has given its green signal to about

120 new zones in private sector in the

last few months.

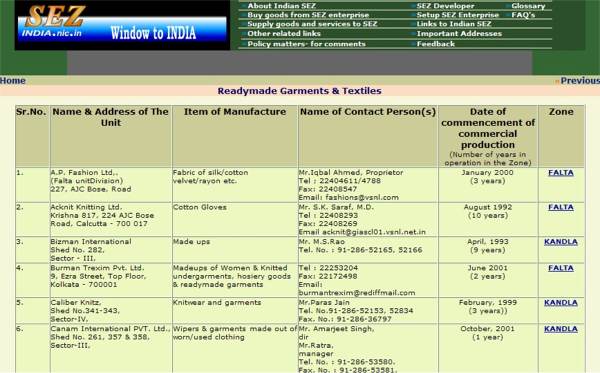

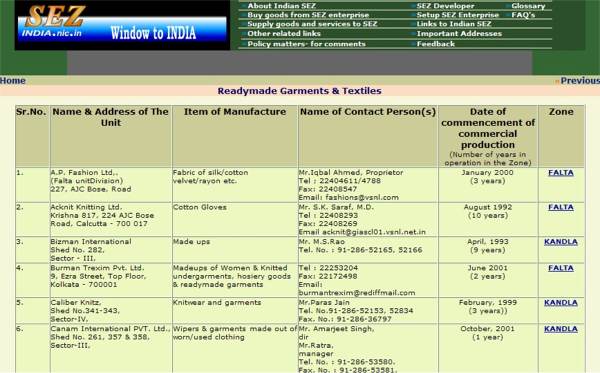

A snapshot of Textile and Garment SEZ enterprises

listed the Government of India's SEZ website: www.sezindia.nic.in

Costs and benefits

To woo investors to the zones, the central government has been offering a number

of fiscal incentives and concessions. For instance, the zones are deemed as

foreign territories as far as trade operations, duties and tariffs are

concerned. The units (100% export oriented) also have full flexibility in

operations. They are exempt from all direct and indirect taxes. No export and

import duties, no excise duty, no central or state sales tax and no service tax.

The units do not require license for importing capital goods and raw material.

100 per cent FDI is allowed in the zones. Repatriation of export profits is also

allowed.

With the new SEZ Act 2005, a new sop is available to firms operating in the

zones. The firms are eligible for getting an extended Income Tax holiday for 15

years: 100 percent exemption for the first 5 years, 50 per cent for next 5 years

and then in the next five years, the income ploughed back for investment in

capital goods is exempt up to 50 per cent. SEZ developers are also entitled for

exemption from income tax for 10

years. The only condition imposed on the firms is

that they must have a positive

net foreign exchange earning (NFE).

Recently, a zone developed by the cell telephone giant Nokia has started operations

in Tamil Nadu. All the units in the zone manufacture components of Nokia mobile handset.

SEZ rules stipulate a minimum area of 1000 hectares for multi-product zones.

To develop these zones, only big players can enter the fray.

What does India, or for that matter any other developing economy, benefit from

providing the zones and their units with fiscal, forex and exim incentives and

making them secure by administrative, legal and regulatory regime? A report on

the Export Processing Zones by the Comptroller and Auditor General Of India

(CAG Report 1998) had highlighted that "Customs duty amounting to Rs 7500 crores

was forgone for achieving net foreign exchange earnings of Rs 4700 crores and

the government does not seem to have made any cost benefit analysis." In spite

of this caustic comment, the Central Government, in the 1999-2000 Budget raised the

corporate tax holiday period in EPZs from 5 to 10 years.

It may be of relevance here to refer to another CAG report, which covers not

just EPZs, but all export promotion schemes. The Union Government has forgone a

whopping Rs 39,704 crore of duty under export promotion schemes during 2003-04,

accounting for 82 per cent of customs duty collected in that year, a CAG report

has said. The duty was forgone under schemes relating to advance license, duty

exemption pass book (DEPB), export promotion capital goods (EPCG), export

promotion zones (EPZ), export oriented units (EOUs) and refund under drawback

and other schemes, the report said. In the previous two fiscal years, the

concessions amounted to 62 per cent of customs duty collected and in 2000-2001

it was 43 percent.

But those who argue for SEZs underline that thanks to the incentives offered,

foreign investors have been encouraged to invest in countries that would

otherwise not be the natural choice for FDI. A report "SEZs in India:

Attracting Investment" sponsored by the Commerce Ministry and prepared by the

Industrial Development Bank of India (IDBI) in 2002 contends that "national

loss" should be weighed against benefits such as foreign direct investments,

export potential, generation of employment, transfer of technologies and skills,

and economic growth of the country as a whole.

The reality

But do these general claims hold water? What kind

of jobs do these zones

generate?

Are these investments secure from the host nation's point of view?

Will the investors remain in these countries if the financial incentives are

withdrawn or if the cost of labour increases?

A world-wide study conducted by the International Confederation of Free Trade

Unions revealed in 2004 that despite the incentives offered by the governments,

the zones (SEZs, EPZs and FTZs) often fall short of their goals. The ICFTU was

set up in 1949 and has 234 affiliated organizations in 152 countries with a

membership of 148 million. The study highlights many reasons for the limited

benefits derived by the host countries from these zones.

First, investments are usually short term, with companies moving to other zones

that offer better incentives. Globalisation of economy and trade liberalisation

accentuates the tight competition between the zones of different countries. To

win the race for investments and to retain them, more and more incentives and

concessions are offered to multinationals often resulting in less gain for the

host country. Legislations also allow easy exit for investors whenever they

want.

A study of female factory workers at the Madras Export Processing Zone

by the Madras Institute of Development Studies revealed that the women

suffered from a number of pains, allergies and other ailments due to tension

and working conditions.

•

Special Exploitation Zone

•

Minimised by the law

Besides, with the growth of the global production network, it's easy for the

MNCs to source goods and services throughout the world and reconfigure

production lines quickly. A country or a supplier will be cut out

from the network if they fail to respond to the increasing demands of the global

market rapidly enough.

International trade agreements too effect investment decisions. For instance,

China's accession to the World Trade Organisation and phasing out of the

Agreement on Textiles and Clothing (ATC) which allocated clothing export quotas

to developing countries have accelerated the recent trend of shutting down

operations in various EPZs throughout the world and relocating to the Chinese

zones. The International Textile, Garment, Leather Workers' Federation (ITGLWF)

had estimated that the phenomenal rise of China would lead to a million job

loses in Bangladesh (an estimate confirmed by the UNDP), another million in

Indonesia, around 200,000-250,000 in Sri Lanka, several thousand more in the

Philippines and many other countries. Hundreds of factories have closed down in

Mexico since their orders have gone to China which offers cheap -- and perhaps

the most exploited -- labour.

The ICFTU study also points out that companies in the zones bypass local markets

by importing their raw materials, which brings little benefit to the host

country. Also, there are no strategies or agencies to facilitate the transfer of

technologies and skills to the domestic market. And since most companies

operating in SEZs do so independently, there is very little communication

between them and domestic firms. The investors usually limit their activities in

the zones to simple processing operations, thus limiting the transfer of

technologies and skills. Thus neither the workers nor local industry gains much

from the zones.

**

Statistics available from the Commerce ministry reveals that the average annual

EPZ export growth rate declined continuously. During 1966-1980 average annual export growth

rates of EPZs was over 77%, whereas during the post 2000 period (2001-2003) it

came down to 7%. The reasons generally attributed are growth of exports outside the

zones and the fact that bulk of the exports from EPZs was to the former Soviet Union and

East European countries. These nations were not too bothered about quality and price as

there was little competition. But with the break up of USSR and the East European block,

the scenario changed and exports declined.

Likewise, while the net foreign exchange earning in absolute terms increased

phenomenally after the mid 1980s, the rate at which it grew remains stagnant,

and in fact, started declining after 1998. Also, more than half of the foreign

exchange earned by the industrial units through exports is spent for importing

goods and raw materials. For instance, in 2004-2005, exports from Madras Export

Processing Zone (MEPZ SEZ) amounted to Rs.1590 crores. However, Rs.859 crore was

spent for imports.

In the present circumstances, do exports per se justify an income tax

rebate? In the past, when the country was starved of foreign exchange, the

Central Government decided to give exports a special break. It was justified

then. But to create income tax-exempt zones now in the name of foreign exchange,

when India's foreign exchange reserve has crossed $140 billion appears without

justification. Incidentally, for export oriented units (EoUs) outside the zones,

there is a sunset clause on income tax. Section 10-B of the Income Tax Act envisages

their income tax benefit will end in March 2009. The SEZs though are governed by

the new SEZ legislation.

Zones and employment

It's true that the zones in the country provide thousands of people with their

livelihood. When the Kandla zone became operational, it had only 70 employees.

Now over one lakh people work in 946 units in different SEZs, and with the

number of zones increasing sharply, as the Commerce Minister points out, a few

more lakh employment is expected to be generated. There will be more economic

activities as a result of the ripple effect of these employments. (1 lakh =

100,000.)

However, the gains generated by SEZs in terms of employment cannot be viewed as

long-term. Apart from providing the best infrastructure, the zones entice investors

with promises of cheap labour and peaceful work environment. According to a

study conducted by Society for Participatory Research in Asia (PRIA) on the

plight of workers in Indian zones, few workers have long-term employment

contracts. Short-term contracts are used for flexible hiring and firing and for

avoiding costs such as maternity and redundancy pay.

Since the industries are export-oriented, the emphasis is on minimising

production costs to competitively price the product in the international market.

Women workers constitute 70-90% of the workforce, and it is they who bear the

brunt of the competition. To meet the production targets, they are compelled to

work harder and longer until they burn out or quit. They work 10-12 hours a day

without or improper overtime payment. Minimum wages are not paid. Social

security benefits are not implemented. Women are forced to work in the night

shifts. Maternity leave is not allowed and sexual harassment of women workers is

common in the zones.

Though, unlike in many other countries, in India, labour laws are applicable to

the SEZs too, in practice, they are rarely implemented. Workers hardly benefit

from any of the labour laws not just because the laws are not implemented

properly but also because there are many loopholes in the existing zone

legislation. For instance, all the zones in the country have been declared as

'public utilities' under the Industries Disputes Act and complicated procedures

restrict the workers from going on strike. A minimum of six weeks' notice is

required before resorting to strikes. Restrictions on the right to join trade

unions, right to collective bargaining and the right to strike are common

features of all zones. Companies campaign strongly against trade unions and

threaten the employees with dire consequences if they associate with unions.

Except in emergency situations, state government agencies themselves require

prior permission of the Development Commissioner to inspect the industrial units

in the zone.

Hard work, strain and stress due to stiff targets and unhealthy work environment

have taken their toll on the workers' health. A study among female factory

workers, mainly at MEPZ, done by the Madras Institute of Development Studies

revealed that the women suffered from frequent headaches due to tension and

intense concentration on work, acute back pain, joint pains, swelling in the

legs, severe abdominal pains, various types of allergies, skin ailments, and,

piles (the result of working sitting in the same position for hours on end). The

majority of women working in the garment units suffered from respiratory

disorders such as asthma, long-lasting coughs and breathlessness.

It is true that international buyers insist on healthy and safe working conditions and reasonable wages.

They have a crucial role in determining the working environment in the firms. Some buyers even visit the

companies and place orders only when they are satisfied. There are a few companies in all zones which

abide by the labour laws and cater to the demands of the buyers regarding work environment. They recognise

workers' basic rights and realise the importance of productive labour and healthy industrial relations.

While some lucky employees benefit from this, there are thousands of workers who are trying to

support their livelihoods in an atmosphere of threat, fear and uncertainty.

Development, Export and FDI

More information

Government websites for the export processing zones provide more

information about the zones and firms housed in them.

•

SEZ website

•

Madras EPZ

In fact, no nation has so far proved that real developmentprogress and welfare

of all sections of peopleis possible through exports alone or FDI. In a

submission to World Trade Organisation in April 1999, India itself has raised

concerns of developing countries on the quality of FDI inflows: "

'more' is not

necessarily 'better' in the case of multinational corporate activities in

developing countries. Studies have shown that between 25 and 40 per cent of FDI

has a demonstrably negative impact on host countries. This is the cost in terms

of using scarce domestic resources inefficiently and substantially outweigh the

benefits of national income

" Still, in the World Economic Forum held in Davos

recently, the focus of the India Economic Summit was how India can achieve

Chinese growth rates. Of course, the Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh reiterated

that India was not interested in adopting China's "growth first, equity later"

model.

Why then is India madly running behind foreign investors at the cost of public

resources and the welfare of the workers? (Quest Features & Footage, Kochi)