It has been decades since the Supreme Court ordered that street vendors be given the right to trade, and that the state facilitates this. But in Delhi – as in much of the rest of India - not much has changed for street vendors.

The government has often neglected the issue, and very few vendors have licences that allow them to trade. With their work labelled 'illegal', vendors are often harassed and extorted by authorities, local goons, licensed shop keepers and even the 'pradhans' (leaders) among the vendors.

In 1989, in the case of Sodan Singh Vs New Delhi Municipal Committee, the Supreme Court ordered that street trading was a fundamental right under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution. However, traders cannot select the area for street trading by themselves, as it might obstruct the right of other citizens to move freely under Article 19(1)(d). So it is up to the state to designate the areas for street trading. The apex court order also said that the state's inaction would negate citizens' fundamental right to trade.

Over the years, the court has passed several judgments upholding the rights of vendors, in many cases. The last such order was in 2013 in the case of Maharashtra Ekta Hawkers Union and another Vs Municipal Corporation, Greater Mumbai and others. Prashant Bhushan was among the lawyers representing vendors in the case.

The court ordered implementation of the National Policy on Urban Street Vendors, 2009, which requires setting up of Town Vending Committees (TVCs) in urban areas that would register vendors and allocate them space in designated vending zones. This was reiterated under the Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act that came into effect in May 2014. But most street vendors are not aware of the new law, or any rights they have.

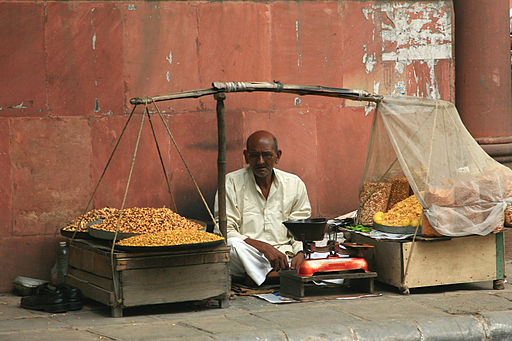

A street vendor selling snacks at Khan Market, Delhi. Pic: Wikimedia Commons

The Delhi government has just initiated its pilot survey of vendors in March. The new Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) government had ordered civic bodies and the police to not displace vendors who had been working in a particular place for many years. The grant of licenses and permanent spaces for vendors, as decided in the ‘mohalla sabhas,’ was also one of the key points in AAP’s election manifesto as well (pages 32-33).

But even so, extortion and eviction of vendors continues as a routine affair in the city. In general, harassment is experienced more by migrant vendors, rather than those who have been working in the same market or area for generations, or those who have been living in the same area.

After the Sodan Singh judgment, in 1990, the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) had called for applications for issuing vending licences (named 'teh bazari'). Those who get the teh bazari are given a 6m X 4m open space for vending. Though a large number of people had applied, only about 900 have been issued the teh bazari, according to the NGO NASVI (National Association of Street Vendors in India). Then again, these were issued only once, in 2001, and never since. Though the corporation did call for applications a few years later, it has not issued any licences to applicants till date.

NASVI, an organisation that works for vendors' rights and tries to organise vendors by enabling vendors' associations in the city's markets, estimates that there are some three lakh street vendors in the city. Much of the vendor population is comprised of migrants, and their numbers keep increasing, their plights worsening in the absence of a licence to trade.

It is not as if owning a teh bazari guarantees rights of vendors automatically, as was illustrated by the case of vendors in Badarpur Vegetable Market. Vendors here had been displaced in 2009 due to the construction of a Metro line and a highway in the area. The corporation stopped renewing their teh bazari the same year.

The market, which was earlier located close to the main road, has now been moved to an obscure area which is not visible from the main road. It is bounded on three sides by land belonging to three different government agencies – the Indian Railways, the DMRC (Delhi Metro Rail Corporation) and the NHAI (National Highways Authority of India). Vendors here say that they now get only half the number of customers as they did earlier.

The many forms and agents of exploitation

Many migrant vendors work within the city's busy markets rather than on streets. On average, such vendors in markets claim to be earning in the range of Rs 200-400 per day. Talk to them, and many will tell you that they end up paying bribes of around Rs 500 per month to the police, non-payment of which could result in harassment and displacement. Vendors, along with their push carts or wares, are often taken to the police station and intimidated. Delhi corporation officials evict vendors, often taking away their wares; inspections are held one or more times a month in the major markets. Vendors say that these officials also collect bribes at times.

Evictions are particularly common during Independence Day or Republic Day, especially if a dignitary is visiting the capital. In preparation for US President Barack Obama's visit during Republic Day celebrations, all street vendors in Lajpat Nagar Market, one of the high-end busy markets in Delhi, were evicted by the police and ordered not to come back for two months.

Lajpat Nagar market, Delhi. Pic: Wikimedia Commons

In markets such as Lajpat Nagar, vendors earn more, but also face greater extortion compared to those in other markets. Manish, a vendor who owns a food stall along a pavement in front of the Lajpat Nagar Central Market, says that he pays Rs 2000 to the police and Rs 1000 to MCD officials every month!

Push cart vendors and hawkers (those who keep wares on their person and sell) here often have to run from lathi-wielding police officers. Many security guards employed by the bigger shops here are also given the responsibility to spot such vendors and chase them away or even beat them up.

Rajnish Kumar thus spends much of his time avoiding the police, corporation officials and security guards. Originally from Uttar Pradesh, Kumar had come to Delhi in 2001. At the time he started work as a direct marketing personnel for a private company. However, commission for the work was insufficient to meet ends and he started street-vending a year later.

Selling orange juice in his push cart, he has to run from the market at least twice a month. “If I don't give money to either corporation officials or the police, they will come again later and harass me. They usually take bribes; only twice in the last 13 years have they issued challans to me. I was also taken to the police station twice,” says Kumar. A widower now, he has a three-year old son back home in his village, and is quite sure that he would not let his son follow in his footsteps.

Vendors in Sewa Nagar market say that they get displaced at least once or twice a month. However, many return to the same market and continue working until the next displacement. Often vendors come to know of the visit of corporation officials much earlier through their informal networks, and vacate the area around the time of the scheduled visit.

Licensed shop keepers also harass vendors and extort money from them in the name of 'allowing' them to work in the area. In Sewa Nagar, for example, 45-year-old Harish Kumar pays Rs 7000-8000, which is half his monthly earnings, to the owner of the shop in front of which he parks his fruit cart.

In markets such as Sewa Nagar, money is also collected by the local mafia. The presence of mafia in this market became particularly visible in the early 2000s when the civil society organisation Manushi Sangathan – headed by activist Madhu Kishwar – initiated a project to develop it as a 'model market'.

The organisation worked with the corporation, based on a court order that had given the go-ahead for the project. It arranged licences for many street vendors, got the market cleaned and facilities arranged for. This affected the mafia which thrives here by extorting and intimidating vendors.

Some street vendors, along with Manushi activists, were attacked a number of times. Only a part of the market could be brought under the project because of stiff opposition from vested interests. Finally the project had to be abandoned in the late 2000s. The market is now maintained poorly and the mafia remains strong, especially in the areas that could never be covered under the original project.

Poor organisation, no awareness

One thing that makes these street vendors particularly vulnerable is the fact that they are not members of any unions or associations. Most vendors believe that given the fact that they hardly wield any influence themselves and are entirely devoid of external support, they would not be able to build an effective organisation.

Street vendors’ compulsions to move from one area/market to another, both to improve their business and to escape from authorities, prevent them from building stable local organisations. However, across all markets, they say that they would be interested in becoming part of any strong organisation, if they had the opportunity.

Even where associations do exist, they seem dysfunctional or inadequate and sometimes, even exploitative. Prabhu Market, which is adjoining Sewa Nagar Market, is one of the very few markets that have functional associations. The association here was set up by NASVI. The pradhan here was elected directly by members. Meetings are held once a month during which issues of vendors are discussed, and steps are taken to interface with various government authorities.

In Batla House, a local association started recently by a few vendors has not yet become popular. Most vendors are unwilling to join the association, saying that it has no power. Mohammad Tasleem, a 35-year-old vendor in this market, says, “The association collects Rs 100 for membership and another Rs 50 every month after that. Yet they themselves continue to get evicted by MCD, so what is the point of joining them?” Vendors like Tasleem here are trying to find out about larger organisations that can support them.

Markets like Lajpat Nagar and Badarpur have organisations too, but with many shortcomings. In Lajpat Nagar Market, for example, the Pradhan (the leader) was nominated by a few vendors, the process being facilitated by NASVI last year. However, very few vendors in the market are even aware of it. In fact, even some vendors who work in the same lane as the Pradhan, were unaware of the existence of the association.

Pradhan Mohammad Salim says that the association has been able to bargain for the rights of vendors by citing court orders and the new law. However, only a segment of vendors seemed to benefit from this, especially those who have been working in specific spaces in the market for long. An eviction drive against push-cart vendors was going on, based an order by the National Green Tribunal.

Salim admits that the eviction drive contradicts the 2014 law, but says that he cannot help these vendors as they are not part of his association yet. In fact, he blamed push cart vendors for not taking the initiative to become association members. In Badarpur Market, many vendors report being extorted by Pradhans themselves!.

Extortion is also common in the ‘weekly markets’ of the city – a system in which vendors set up their wares along a stretch of the road in a specific area on a specific day of the week. Different areas have weekly markets on different days. Though the system has always existed, it got the formal approval of the Delhi municipal corporation (MCD) only in 2002. Arjun Singh, the President of the Dilli Pradesh Redi Patri Sapthahik Bazaar Welfare Society, credited his Society with holding long-term protests that led to the corporation's 2002 directive.

Singh is among those who now run the weekly market in Sheikh Sarai. But vendors who come here say that weekly markets, including that of Singh, extort money from them. As per the rules, vendors are supposed to pay only a fee of Rs 15 to MCD officials for the specific day on which they work in these markets.

Yet another vendor in the Sheikh Sarai market, on condition of anonymity, says, “In this market, the Pradhan collects Rs 100 from us per table (on which wares are displayed). Pradhans in all weekly markets collect money, and I end up paying Rs 3000-4000 per month for this. If we speak up, the Pradhans may attack us or they may get the police to act against us.” He says that he pays Rs 200 per day to Pradhans in Sheikh Sarai while earning only Rs 500-600 overall.

Ask shoppers, and many of them feel that vendors within markets should be allowed to work. Devika Sharma, a 21-year-old avid shopper in South Delhi markets, says, “With street vendors in markets, I feel I have more choice. Vendors in main roads or near residential areas may cause nuisance by obstructing people's movement or create unwanted noise and congestion, but those within markets do not cause any problems.”

However, judging by the current scenario, it may take long before vendors are actually able to secure their legal rights.