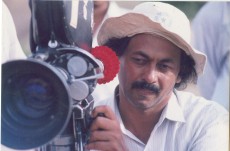

The extremely low-profile and reclusive Girish Kasaravalli is one of the best filmmakers of Karnataka; indeed he is one the best that modern India has produced. His insight into women's psyche is so deep and its treatment so low-key, subtle and controlled, that the inner strength of the female protagonist - whether in Thai Saheb, Haseena or Dweepa - takes you completely by surprise. The men define a counterpoint to the strong and courageous women of these films, a telling attempt considering that the filmmaker himself is a man.

Unfortunately, film lovers across India remain mostly in the dark about Kasaravalli's works. A graduate of the Film and Television Institute of India, Pune, Kasaravalli makes films that may lack 'mass appeal' but as serious works that focus on social and political questions, and on the forces that shape an individual's behaviour, they are in a class all their own. Though he is not a prolific filmmaker, his films have won top awards at the National and State Awards and have done the rounds of noted festivals abroad.

His latest film Gulabi Talkies is a beautiful celluloid essay on the trials and tribulations of a poor Muslim woman, Gulabi, a midwife, whose life and the lives of other women and children in a small fishing village in Karnataka change when she is gifted a television set. Gulabi Talkies won the top prize under Indian Competition section at the 10th Osians-Cinefan Festival of Asian and Arab Cinema. The lead actress Umashree, bagged the Best Actress award for her outstanding performance in the film.

Gulabi, an expert midwife, leads a lonely life in a small island village of fishermen. Her husband Musa, a small-time fish-selling agent, has deserted her and lives happily with his second wife Kunnipathy and their child Adda. Gulabi adds meaning to her life by watching films. She slots a regular time every day for the latest release. The neighbourhood knows where exactly to look for Gulabi when a call arrives from a woman going through labour pains - it should be in the local cinema hall. If she is too caught up in the movie, Gulabi even refuses to oblige a client at the cost of losing money. Yet, she is in great demand for women in labour.

Unfortunately, film lovers across India remain mostly in the dark about Kasaravalli's works.

All this changes when, as bonus for seeing a rich housewife through a difficult delivery, the family gifts her with a television set and a satellite connection. Gulabi's is the second television set in the island village. Women and children begin to crowd her hut every day to watch their favourite films and television serials, hooked to the next episode the following day.

With the television and the satellite connection are installed in her tiny hut, Gulabi stops going to the theatre. She watches films and serials right inside her hut, along with the rest of the women in the neighbourhood and their curious brats. She shoos them away when she feels they are a hassle and counsels Nethru, a young girl whose husband is away and whose mother-in-law harasses her all the time. The locals begin to eye Gulabi with a certain degree of respect. Her two-timing husband visits more frequently, but she soon realises that he is exploiting her and throws him out.

The film locates itself in the 1990s against socio-political changes happening in Karnataka. This places the film in a definite setting, composed of different bits - the Government of India's decision to allow large fishing vessels from other countries to operate along its shores, and the resulting threat to livelihoods of fishermen; wide-spread communal tensions in the State, with right-wing views ascendant; the State Government's decision to install one TV set in each of the Gram Panchayats. These apparently unrelated pieces form the backdrop to the film, and influence the story of Gulabi and her final catharsis.

Kasaravalli's screenplay is tightly knit. Yet it cuts seamlessly into the economic and social changes in the fishing community from all these changes, and captures the breadth of those changes through the lives of one family.

The film is based on a story by Vaidehi, which Kasaravalli says he "had read a long time back. She is one of the best-known and widely read women writers in Kannada literature. But the story came back to me in a different situation. A few years ago, I had to make a speech on the politics of images in a remote corner of Karnataka. While I was researching my paper, I found CNN beaming the image of Saddam Hussein captured by US forces. To me, these images appeared to have been doctored [Eds note: As it turned out, Hussein had indeed been captured] I brooded over them as the subject continued to haunt me."

"Have we turned into willing/unwilling targets of people who, under the guise of giving news, are actually forcing their opinions on us? Was the media today manufacturing opinion instead of delivering it or acting as an agency? Were we looking at something immediate through tinted glasses provided by so-called information technology instead of looking at things from an understanding born out of our experience," he asks.

Kasaravalli made some changes to Vaidehi's story, to reflect his motivation for making the movie. "I decided to rework the story. I changed the geographical base of the story to a fishing village. I converted Gulabi to a Muslim woman. In the story, she is Christian. I introduced Musa and the kid. As we went on writing and rewriting the script, issues like loneliness and the craving to belong, desire and disappointment, hope and aspirations, global and local harmony and conflict began to knit themselves into the story," he details.

The world comes marching in

Nethru, the young wife, perhaps taking a cue from the soaps she watches in Gulabi's house, runs away, and Gulabi is held responsible for bringing shame to the girl's family. In this sub-text, Kasaravalli suggests how television serials can influence a cloistered woman's decision in a village situation, never mind that she is betrayed in her bid to escape and find a fresh life.

There are other sub-texts to the theme of an external world imposing itself - physically as well as through the tube. The rich new trawler-owning fishermen dupe the locals with false promises, leading them to penury. And more critically to the narrative, communal schisms from the outside percolate down to the village where Gulabi, the only Muslim woman, is an easy target. Some people feel she is the cause of communal tensions, and chase her out of the village where she has lived all her life. As they begin to bring the hut down, pull out the cable wires, they leave the television set intact for others to take away. Gulabi is so strong and firm in her conviction that they have to literally carry her, sitting erect and rigid on her small wooden seat to take her to the boat.

"I had forgotten that my name is Gulab-bi," she says wistfully, reminding herself that the only reason she was being driven away from her roots was her religious identity. "You cannot take my livelihood away. Women will continue to have babies and I will continue to make a living out of it," she tells her tormentors as her boat takes sail to her new address.

Rather than telling the story of an individual, Gulabi Talkies, typical of Kasaravalli's cinema, sets her personal tragedy against a larger political and social canvas in transition. It offers multiple perspectives without sound or fury. It is a political statement on the oppression of groups of poor fish traders victimised by a government decision made without considering the consequences of the decision on local livelihoods. It is a social statement on victimisation of a woman on communal lines for flimsy reasons. It is a powerful comment on the power of the media like television and cinema on the lives of the people. It is a statement against the oppression of an innocent woman who does not know how to defend herself legally or socially.

But with all this, it is also a tribute to the strength and courage of a woman who keeps her dignity intact in the face of severe obstacles in life. And without that personal element, the larger narrative could simply not be anchored in the same way. Kasaravalli instinctly recognises this, and in doing so, he helps the audience too blur the lines between the personal and the political.

The crew, and the filming

If the story seems so natural, then it is because so many others have contributed critical pieces to showing it plainly, yet powerfully. M N Swamy and S Manohar's editing moves fluidly through time and space, capturing the finer nuances of changes in the weather of the sea-side village, the scenes in the market place, of the fishing union's office, or the dark interiors of Gulabi's small hut with the television shedding its own light and sound, matching S Ramachandra Aithal's cinematography perfectly. Isaac Thomas Kotukapally's background score is telling, soft when emotions take priority over social statements, offering the right support to the powerful script. Ba Su Ma Kodagu's production design deserves an award especially for the hut interiors and the village neighbourhood.

And to think that Umashree is better known as a brilliant comedienne on the Kannada stage and screen. She later gravitated to character roles. She has a political background too. She was elected President of the Women's Wing of the now-defunct Krantidal, a political outfit of former Chief Minister S Bangarappa. When Bangarappa dissolved the party and joined Mulayam Singh Yadav's Samajwadi Party, she switched over to the Congress and was a legislator for one term. Kasaravalli saw her portray a 70-year old woman looking for her lost hen in a stage version of Dalit writer Devanuru Mahadeva's novel Odalala, and was instantly set on her as his choice for Gulabi.

"We shot the film in real locations, a practice I generally follow for all my films," says Kasaravalli. "I found a spot that suited my requirements and asked my art director, also a theater director and a graphic artist, to construct a hut with removable thatched walls. The story demanded a rock beside and a series of boats lined up along the shores. Our spot had all of these. My unit members were surprised when they saw how precisely the location matched the description in the script."

"The local villagers were very cooperative. We mingled with them freely, as if we were one of them and we did not look down or them or show disrespect in any way. We did not ask them to move out of the frame even if they were crowding around all the time. We would take only those shots, which would not interfere with their work. We did the remaining shots once their work was over. This earned us tremendous faith. Umashree, who played Gulabi, a familiar face, for them, mixed freely with them. They posed for us whenever we asked them to," he recalls.