A new study by the London-based Overseas Development Institute, titled “Towards a better Life: A cautionary tale of progress in Ahmedabad” may provide a glimpse of what former Chief Minister Narendra Modi may have in mind for other cities in the country.

In many respects the Gujarat capital under Modi, who was CM from 2001-2014, has made remarkable progress. “Across Gujarat, the urban poverty rate declined from 28% in 1993-1994 to 10% in 2011-2012, at a rate slightly ahead of the national urban average. This was achieved against a backdrop of significant economic growth nationally,” says the study by Tanvi Bhatkal in London.

“There has also been a dramatic decline in the share of Ahmedabad’s population recorded as living in slum settlements, from 26% in 1991 to 4.5% in 2011, and improving the wellbeing of slum dwellers.” Similarly, “extending water and sanitation services to slum communities, regardless of tenure, has been an important step towards their integration into the city – which was enabled by the involvement of civil society working alongside government.”

The study, based on interviews with 50 stakeholders and experts, provides a useful lens to explore “how a rural-urban transition can be managed to benefit poor communities. Three dimensions are singled out:

- Material well-being, including income, access to finance and housing

- The environment, with a focus on environmental services and the management of urban expansion

- Political voice, through an increase in collective action and stronger local governance

However, the study cautions: “It must be noted, however, that progress has not been linear: it has been characterised by peaks and troughs as certain challenges were resolved and others emerged. ... Further, while there have been significant gains in Ahmedabad, there have also been signs of a recent slowing or even reversal of progress for poorer households.

“A number of recent top-down urban development policies - even those intended to benefit poor families – have negatively affected poor people and damaged relations between government and civil society as they failed to understand people’s concerns and priorities. … Moreover, the shift in policy focus – aimed to attract investment by creating a ‘global’ city – demands rethinking how progress is defined and whom it is intended to benefit.”

While the city was once coupled with Mumbai as a “Manchester of the East” for being a major textile centre, it lost that status when it rapidly declined in the 1970s. However, the study shows, it has witnessed the emergence of many other industries including petrochemicals, refining, pharmaceutical and chemicals, automobile, and agro and food processing enterprises.

At the same time, about 80% of workers worked informally as either wage workers or were self-employed in 2010. Changes in the nature of employment have included a decline in regular employment and an increase in self-employment, according to the foremost scholar of Ahmedabad (along with Prof Jan Breman in Holland), Prof Darshini Mahadevia of CEPT University in the city.

This has been the result, in part, of the outsourcing of many manufacturing activities to home-based workers and informal retail trade. Retail trade alone employed 31% of the district’s workers in 2005, most of them in small enterprises.

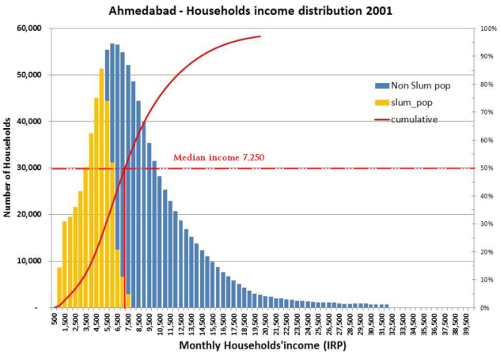

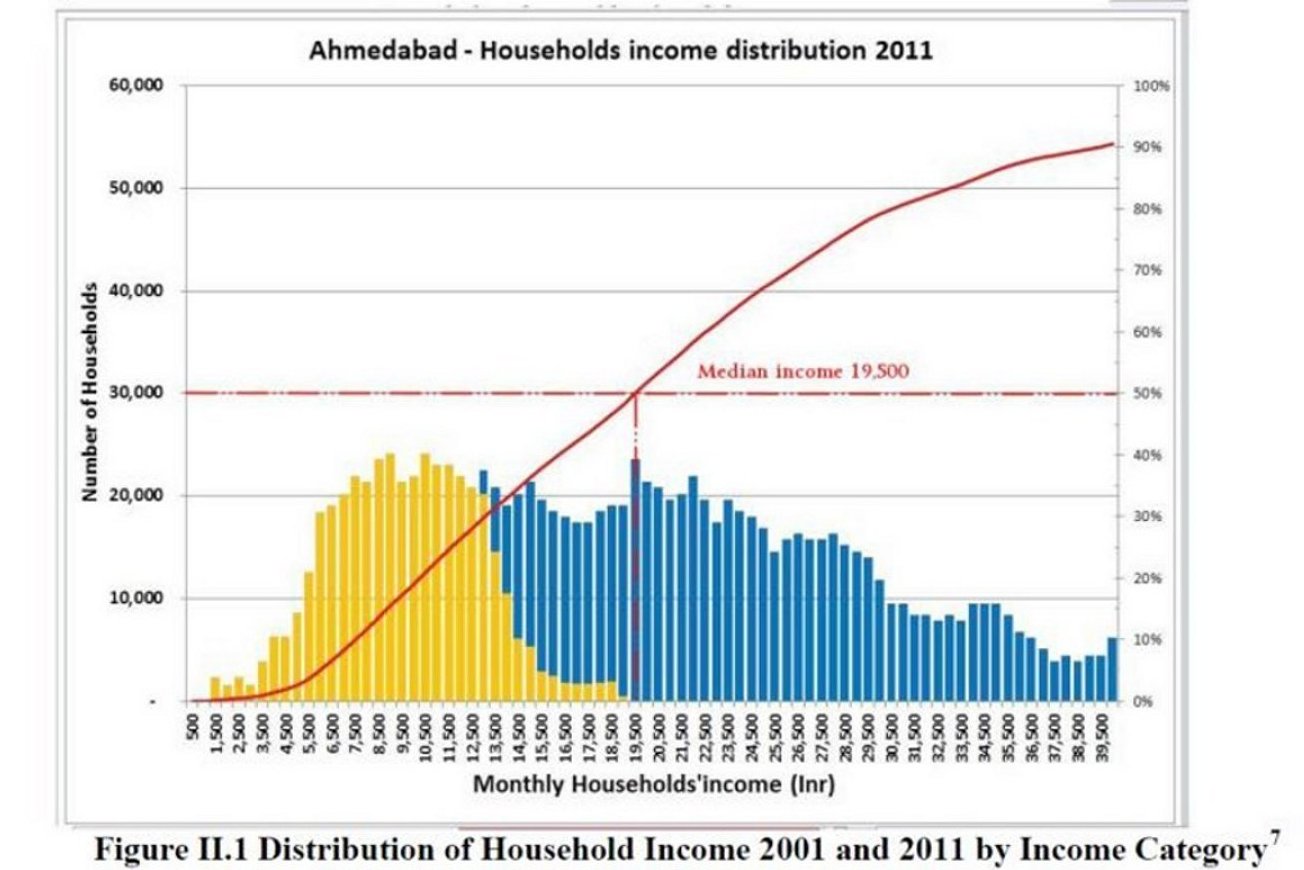

Earnings have increased even among the poor, while the median household income increased from Rs. 7,500 to Rs. 19,500 a month between 2001 and 2011:

Ahmedabad median household income distribution, 2001 & 2011. Source: Clarke-Annez et al., World Bank, 2012

Ahmedabad has demonstrated some of the aspects of smart growth, a pointer of the direction that the PM’s 100 smart cities will take in future. While the Bus Rapid Transit System (BRTS) failed in Delhi in Pune, it has proved a remarkable success in Ahmedabad (as well as Indore and Surat).

But an undated UN Environment Programme study of the BRTS in five Indian cities, of which CEPT was part, found: “The survey of 1,040 BRT system users in Ahmedabad showed that the sex ratio of the working population amongst the users was just 226, indicating that working women did not use this system much as compared to working men.

“The use of the BRT system by low-income groups is also not very significant. Of the total users, just 13.7% belong to household with incomes of up to Rs. 5,000, 62% had monthly household incomes of more than Rs 10,000. This is in spite of the fact that a large number of low-income group housing and slums fall within a 500-metre radius, or walking distance, from the BRT network. Many of the BRT users are captive public transport (PT) users who used public transport prior to the BRT project.”

A city profile in 2014 by the Centre of Urban Equity at CEPT, also led by Mahadevia, found that a very large proportion -- about a quarter among the males and about two in every five among females -- use the BRTS for social purposes. It is possible that many of such trips have been induced by a new mode of transport in the city. For example, BRTS connects western Ahmedabad to the recreational facilities located at the Kankaria Lake in the city’s southeast. In other words, BRTS has made the long-distance recreational facilities more accessible for the middle-class from western Ahmedabad and created new demand for transport.

However, only 42 per cent of Ahmedabad’s users were taking BRTS for more than 21 days in a month, which means that the BRTS still has more ground to cover in finding regular and sustained ridership in the city.

Another Ahmedabad project which has run into controversy is the Sabarmati River Front Development. It resettled a huge number of street vendors and slum dwellers to the distant suburbs, where they were disconnected from their jobs. The ODI study doesn’t cite the environmental problems the project has caused by “concreting” the banks of the river, creating artificial gardens and promenades and – most worrying of all – hiving off a certain amount of reclaimed land to sell as real estate to fund the project.

The concrete banks of Sabarmati River, Sabarmati Riverfront Development. Pic: Alex Follmann (India Together files)

The study points out that when plans were to be implemented in 2005 without consulting communities that would be displaced without rehabilitation plans, residents came together to form the Sabarmati Nagarik Adhikar Manch, facilitated by NGOs. A PIL was filed by the river front dwellers through the well-known lawyer and human rights activist, Girish Patel.

Writes Mahadevia: “The court gave a stay order on evictions, asking the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) to submit an R&R policy to the court, which AMC did three years later.

“Moreover, this Resettlement and Rehabilitation (R&R) policy was minimal and ambiguous, and given the AMC’s politics around riverfront development, the resettlement process that unfolded under this policy was deeply problematic.

“The R&R policy was implemented in haste in spite of forming a R&R monitoring committee, which resulted in wrongful inclusions and wrongful exclusions.

“In many cases, slum residents found it difficult to prove their eligibility, having lost important documents in the river’s floods or during communal riots. Many were not able to submit proof documents since neither ration-cards nor election cards had been issued by government authorities since 2007.

“Many were harassed due to incorrect spelling of their names in the surveys and insufficient proof documents. When the resettlement process began, it was based on a 2002 cut-off date, which was later extended to 2007, and finally to 2011; these extensions happened through contentious processes involving forcible demolitions by AMC in the midst of the resettlement process and court orders following this.”

At the same time, Modi was able to leverage funds for the city’s development, according to ODI. In 1997 AMC was awarded a credit rating of A+ by CRISIL (a Standard and Poor’s company in India), which was later upgraded to AA. “Following this, the AMC become the first municipal body in Asia to access the financial markets and issue municipal bonds, worth Rs. 1 billion ($26 million) without a government counter-guarantee in 1998,” says the study. “The success of this foray into the capital markets has been emphasised by a strong credit rating, enabling AMC to raise capital to help finance a large city-wide water supply and sewerage project in the late 1990s.”

Bhatkal told this writer: “In terms of how the poor have been excluded in recent large projects, there have been challenges in both design and implementation. Our interviews brought out how there has been the displacement of a large number of slum dwellers in, as has been well documented, and issues in the manner in which they were relocated - in terms of who was eligible for relocation, where and how they were relocated, and the lack of consideration with which this was done even after communities went to the courts that ordered the government to make provisions for rehabilitation.”

If one was to give Modi’s Ahmedabad a report card, it would have to be several pluses and a few minuses. The thrust of all policies was to benefit the middle and upper classes, while the poor were often left to stew in their own juice.

Mahadevia faults the ODI study – like other analyses of Indian cities by foreign scholars and institutions – for being too soft on the powers-that-be. It does cite the 2002 communal riots, but only in passing, referring to it being dubbed (after a foreign scholar) as a “shock city”. It quotes an unnamed sociologist as saying: “The voices challenging the new conception of ‘development’ proposed by the government can’t be heard, and the breakdown of trust will overshadow future collaboration.”

These patterns may crop up with grandiose nation-wide urban development plans masterminded by the current regime. These include the multi-thousand crore Delhi Mumbai Industrial (rail) Corridor, some 150 km on either side of which will be urbanized, and the Gujarat International Finance-Tec City, located between Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar, which is a “central command and control” Rs 70,000 crore smart project.

While cities may get ‘smarter’, will the poor be excluded?