Sixteen years after the Supreme Court of India gave directions to employers in the Vishakha judgment, the Government of India enacted and enforced a law on sexual harassment at workplaces. The new law follows the framework set by the Supreme Court Vishakha guidelines (1997).

While this is surely a step forward, the law also contains several spots needing discussion. These are complex and may not have instant answers. Yet, it is imperative to focus on these, especially four prominent areas that have the potential to influence the implementation of the said law.

These would be the role of the Internal Complaint Committee (ICC); the definition of sexual harassment; issues concerning false and malicious complaints; and finally, gender neutrality of the category of complainant within sexual harassment policies.

Role of Internal Complaint Committees (ICC)

“He has such gentle disposition. It is highly improbable that he can say such things. He was speaking so politely while deposing. You were also there. Did you not notice this? “– Complaint Committee Chairperson, Chaudhuri (2008)

Section 4 of the Act mandates constitution of an ICC via a written order by the employer at every workplace. Under the Act, ICC is the chief mechanism empowered with authority of a civil court for resolution of complaints, firstly through conciliation and finally through an inquiry. With such enormous powers vested, the biggest challenge before the employer is to choose the ICC members suiting the specific requirements for intervening in situations of violence against women and carry on sustained capacity building.

It is important that the ICC members are able to inspire confidence among women and are accessible to them. They should remember that absence of reporting on sexual harassment does not always mean it is nonexistent. Whenever a complaint is reported, the alternative of undergoing conciliation under Section 11 should be exercised by the ICC with extreme caution. There is always a danger that women will be pressurised and silenced under the guise of conciliation.

ICC members need to believe women complainants and not judge them by their moral standards. During the inquiry, it is for the ICC to prohibit slanderous questions based on sexual character, personality and work performance of the woman. As decision maker, the ICC should take note of the socio-economic profile of individuals, their position within the organisation, work culture of the organisation and other related issues.

Finally, the committee members need to remember that they are not merely guardians and implementers of organisational policy on sexual harassment but their actions will have long term implications for the organisation, both internally and externally.

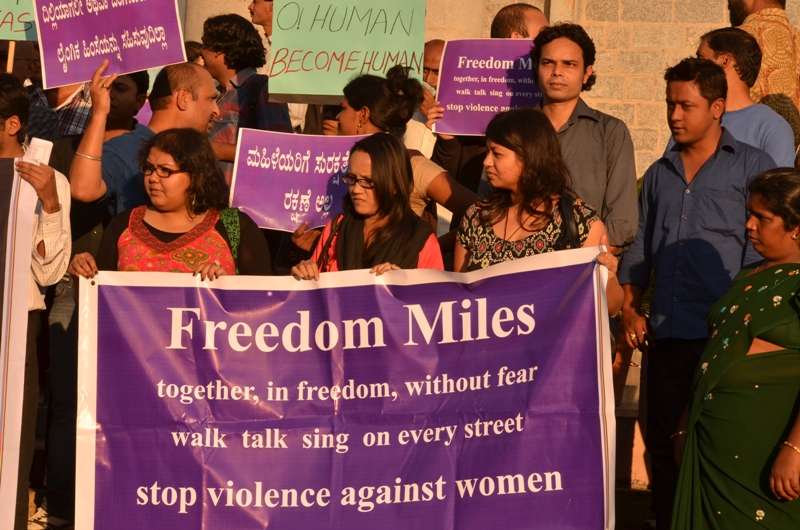

Protests in Bangalore over rising violence against women. Pic: Jim Ankan Deka via Wikimedia

Definition of Sexual Harassment

"I was forced to have alcohol, I was forced to come to parties and I was being forced into a lot of practices which were against my culture and religious practices." - Sayema Sahar Former Head of Creative Cell, Star/ABP News

Section 2(n) of the Act defines sexual harassment as any unwelcome behaviour whether directly or by implication. Though the definition within the Act describes sexual harassment as uninvited and unsolicited conduct which is sexual in nature; it misses the much needed clarification that unwelcome-ness of the behaviour is to be interpreted on the basis of subjective perception of the woman.

The Justice Verma Committee (2013) that reviewed the Act suggested in its report that the definition needed to include the aspect of individual perception of the woman. Whenever a complaint of sexual harassment at workplace is handed over to the ICC, it is crucial that utmost importance be assigned to the impact and effect of the alleged behaviour on the self esteem and productivity of the affected women.

Ample room should be provided by the ICC members to accommodate varying perceptions and comfort levels of women depending on gendered socialisation, cultural beliefs including contextual factors such as location, caste, class and religion, age, ethnic background. Further it is important to realise that sexual harassment results from complex dynamics of gender, power and sexuality. A particular behaviour interpreted as sexual harassment by one woman may not be the same for other women due to diverse personal boundaries.

At the first instance, the woman may not be sure about the unwelcome nature of the behaviour and either ignore it or respond courteously out of compulsion, only to complain at a later date. It is indeed a complex journey influenced by various factors for women to reach a point where they are able to acknowledge and report sexual harassment.

If these factors are not considered adequately, the organisation could run the risk of justifying objectionable conduct as normal, leading to dismissal of valid complaints of sexual harassment and wrongly treating them as out of purview of the law.

False and Malicious Complaints

“There is no physical evidence; it’s one’s word against another’s, really. Even now, for instance, when I appear before the panel, I feel I’m being looked at with suspicious eye. I have to constantly justify that I’m not lying; I’m not making up this story. I feel humiliated.” – Law Intern

Section 14 of the Act states that if the ICC concludes that the complaint was false and done with malicious intent, it can recommend action against the woman to the employer. Such a provision could act as a trap for the ICC members, if they not aware of the stealthy, private and subtle nature of sexual harassment. Use of the section by the ICC without deeper thought can discourage women from reporting complaints.

Though this section was pushed by some under the pretext of preventing misuse of the law, it needs to be understood that sexual harassment at workplace is one of the most under-reported forms of violence against women. Several studies conducted across India point out that complaints of sexual harassment by women are few and mostly considered a last option. This is usually due to shame, lack of family support, apprehension of being labelled as liar, fear of retaliation from the employer / harasser, adverse effects on employment, character assassination at workplace, lack of confidence in the complaints mechanism, and escalation in sexual harassment.

Assuming the inevitable existence of hierarchy and power inequalities at a workplace, it takes humongous courage on the part of women to register a complaint. In such a situation, it is imperative for the ICC to understand that the woman may not always be able to provide direct evidence in support of their complaint and that unlike a criminal trial an internal inquiry does not require strict proof.

Last, but not the least, as stated in the Verma Committee Report, a Red Rag provision such as this reflects little thought and should hardly be the focus of the ICC and the employer; the focus of law is to provide relief to the aggrieved party and not misuse of the same.

Are policies gender-neutral?

“It is important to understand how to create and maintain a gender equitable workplace. This will be a positive approach with focus on prevention. The management comprises mainly of males; they may not be sensitive to problems faced by women. If there is a policy, certain procedures will be laid out and adopted.” – Complaint Committee Chairperson, Chaudhuri (2008)

The Supreme Court of India while issuing directions for employers in Vishakha and Others vs.State of Rajasthan and Others said that sexual harassment of women was common and resulted in violation of the fundamental right to gender equality including right to life and liberty guaranteed by the Indian Constitution.

A Joint Parliamentary Committee report (2011) revealed that in the face of poor implementation of the Supreme Court Vishakha guidelines, a law safeguarding the rights of women at their workplace was needed. The report further said that since there were no studies focused on sexual harassment of men at workplaces, gender based classification of complaints was not possible.

The Committee concluded that given the patriarchal nature of Indian society, the number of women needing redress from sexual harassment at workplaces was high. Sustained struggle by the women’s movement for over fifteen years resulted in enforcement of the law on 9 December 2013. This gender specific legislation acknowledges unequal gender relations at workplaces by recognising specific constraints and needs of women in India. Such legislation is therefore an example of an explicit form of affirmative action under Section 15(3) of the Indian Constitution, which allows the State to enact special laws for women.

Section 13(a) of the Rules of the Act mandates formulation and wide dissemination of internal policy on sexual harassment intended to promote safe spaces for ‘women’ by elimination of causal factors that contribute towards a hostile work environment against women. In this situation, it is imperative that under the said law all employers create policies focused on prevention and resolution of sexual harassment of women. Attempts to include men in the category of complainants within a policy based on the law could be interpreted as contradictory to the Act, and even a violation.

Of course, with respect to sexual harassment of men, there must be separate efforts towards studying the occurrences and creating a database of complaints for it to be dealt with separately in the coming times.

It is clichéd now to say that all of us must continue to work towards upholding fundamental rights of women. While the Act discussed has the same as its fundamental objective, it can be unequivocally said that in its present form, it is fraught with interpretative difficulties and dilemmas as discussed above. It is only when we address these issues and commit ourselves wholeheartedly to creating safer workplaces for women that we will move towards achieving the goal of gender equality.

REFERENCES

1. The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013

3. Sexual Harassment at Workplace: Experiences with Complaints Committees

4. Sexual Harassment At Star – ABP News Ignored by all

5. Justice Verma Committee Report