Stories of Indian corporate acquisitions and investments abroad have become one more indicator of a globally emerging power. Dams and hydropower are now being added to the list of sectors like auto, telcom and steel in which Indian companies are venturing abroad.

The Indian government and some of the public sector companies have been involved for many years in surveying, investigating, designing and building dams in other countries. But this activity has mostly been in the nature of bilateral assistance to neighbouring countries like Nepal and Bhutan, rather than aggressive corporate expansion. This is changing now. Indian companies, both public and private, are foraying into dam and hydropower in other countries, not just as equipment suppliers or construction contractors, but project developers and owners.

The Tata Group has entered into a 50-50 joint venture between Zambia Electricity Supply Corporation and Tata Africa Holdings Ltd for developing a 120 MW hydro project at Itezhi-Tezhi. Closer home, Tata Power took a 26 per cent shareholding in the 114 MW Dagachu power project in Bhutan in January 2008. The GMR group has signed an MoU to build the 300 MW Upper Karnali hydropower project in Nepal. Infrastructure Leasing and Financial Services (IL&FS) is an equity partner in the 750 MW West Seti project in Nepal, while the state owned Sutluj Jal Vidyut Nigam Limited (SJVNL) has been awarded the right to develop the Arun III project in Nepal on a BOOT basis. (The company Builds, Owns, Operates the project for certain years and Transfers it back to the Government after that).

This could just be the beginning, as both Nepal and Bhutan are planning to build a large number of hydropower projects running into many thousands of megawatts and are seeking private finances to develop these projects.

New lands, old questions

As Indian companies export know-how and finance to these countries to build hydropower projects, the important question is whether they will they also export the same attitude and approach towards the social, environmental and other impacts of these projects. People in Nepal are already questioning the record of Indian companies coming in to build these projects. SJVNL, in its earlier avatar as the Nathpa Jhakri Hydropower Corporation, built one of the messiest hydro projects in the country with faulty design and planning, huge time and cost overruns, displacement without resettlement and gross violations of environmental laws.

There are other questions raised by the locals as well - whether the resources of their country should be allowed to be used for the profits of a foreign company. These concerns raise serious doubts about how this expansion of corporate India into dam building in other countries will roll out.

Additionally, there are serious issues about the ethics and responsibilities of these companies. Consider the Upper Karnali project in the Mid-Western area of Nepal. The Karnali river, known as the Ghaghra in India rises in the Himalayas near Tibet and drains an area of about 43,000 sq km before it enters India. In its upper reaches the Karnali flows through a beautiful and deep gorge. In an amazing wonder of nature, the Karnali river makes a sharp hairpin bend and loops back in a path about 60 kms long. This brings the channel within 2 kms of its upstream. At this location, the upstream and downstream parts of the river are separated by a mountain ridge about 2 kms wide, but the height difference between the two points is 150 m.

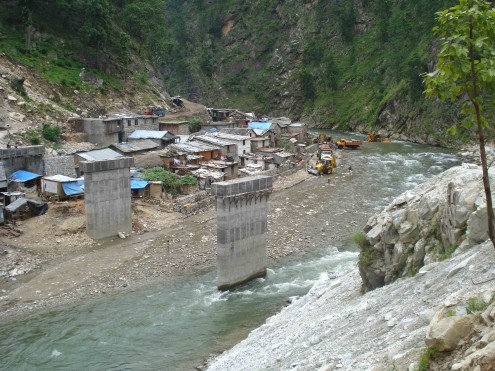

The Upper Karnali project plans to utilise this bend to build a power generation station. The project involves the construction of a dam across the river at the higher point that diverts water through a tunnel to the lower point, generating 300 MW in the process utilising the head of 150 m. The advantage claimed for this location is the very short tunnelling that would be required.

Like most such large dam projects, the decision on this project also seems to have been taken completely bypassing the local people who will be directly affected. Not only have the local people not been consulted, but they have not been informed properly about the project, and its impacts on their lives and livelihood.

Needless to say, the project is likely to have serious impacts. The lands and fields of several villages are going to be affected by submergence. Equally important, the project is likely to lead to a drying up of the whole loop of the river. The dam, and the diversion of water through the tunnel will completely alter the ecology of about 60 to 70 km of the river. One of the most severe impacts would be on fish and on the livelihoods of those who depend on it. The issue of greatest concern however is that none of these impacts have been properly studied or assessed while it has already been decided to go ahead with the project. The MoU requires the GMR consortium to conduct the EIA study and prepare the environmental management plan. This is putting the cart before the horse, a characteristic feature of most large dam hydropower projects.

In July 2008, I visited the dam site and the villages that are likely to be affected by the project. In a meeting held in Ramaghat, where the dam will be built, the villagers reiterated their strong dependence on the river and their close relationship with it. They talked about how the river provided them with drinking water, water for cattle and fish even in the areas where the gorge is deep. In other areas the river also provides water for irrigation. In particular, they emphasised that all communities fish in the river, but one of the economically most backward communities - the bhadi (landless, homeless and so-called untouchable) community - is fully dependent on fishing. They described several special occasions and festivals that are celebrated on the banks of the river including Shivaratri, when there is a big fair where people from the neighbouring districts gather on its banks. The people were emphatic in saying that they cannot survive without the river.

The people were particularly angry about the way they were being treated. In the meeting, a number of people expressed this, saying that nobody from the company or from the government had come and spoken with them or informed them about the project. They strongly protested how such deals are stuck in hotels in Kathmandu without the directly affected people being anywhere in the picture.

The village of Ramaghat will be affected by the dam submergence.

The project developer company had visited one of the affected villages sometime back, but did not hold any substantive discussions with all the people, but instead just met a few of them randomly and informally. In these informal chats, the company officials seem to have promised the people schools and hospitals. However it is unlikely that people are going to be satisfied with these crumbs that are traditionally thrown at the affected populations.

People are raising very fundamental questions about how the government of Nepal allow a foreign company to take away 88 percent of the electricity generated by the project while Nepal itself is reeling under a severe power crises. They are asking why a company should be allowed to make huge profits from a river that belongs to the people.

One important issue that is being raised is the power of the central government to sign away the rights to the river in view of the proposed political restructuring in Nepal. In principle Nepal has agreed to transform itself into a federally organised political entity. Under this structure, water resources would come under the control of the States that are to be formed. There is a demand that these projects be put on hold till the States come into being so that their control and decisions about their own natural resources are not compromised.

At the root of this is a process of increasing demands that the benefits from resource development must be shared with the people at the lowest tiers. It remains to be seen how a company that is building the project primarily for making profits addresses these demands.

These demands are now turning into an aggressive stand challenging the project itself. The Himalayan Times of 10 August 2008 reported that the Maoist-affiliated Autonomous Council of Karnali (ACK) warned all concerned not to visit the Karnali Region with the aim of commissioning major hydropower projects. It quoted ACK chairman Gorakh Bhahadur BC as saying that "the people who visit the far-western region to garner support for major hydropower projects may face people's action ...". He also warned the government and developers to stop their activities and wait till the country is restructured and States' rights over natural resources are established.

In an interaction organised in Kathmandu recently by the Water and Energy Users' Federation (WAFED) Nepal of people from the Upper Karnali area with some members of the Constituent Assembly of Nepal and other experts, the speakers voiced a similar demand asking the government to scrap the MoU with GMR.

Such a stance is not restricted to the Upper Karnali project but is seen in all large scale infrastructure development that is taking place. As Indian corporates - and through them the Indian elite - look to resources in other countries to make profits and also satisfy their rising demands for consumption of energy, these are issues that are going to become sharper.

Indeed, if these issues are seen in greater relief where an Indian company is operating in a foreign land, they are present in equal strength here in India as corporates look to the remote areas of our own country for the same objectives of satisfying the consumption demands of the elite and their own profits.