I am a strong believer in dialogue, says Dr. C. S. Lakshmi with a sparkle in her eye. As Director of Sound & Pictures Archives for Research on Women, this researcher and writer endeavours in recovering womens history, and preserving accounts of it for future generations. But the word archives doesn't describe this work fully; SPARROW doesnt merely collect and document but also actively seeks to communicate. And communicate with a difference, for it wants its history to not be a dreary and remote discipline, but something to be heard, seen, intimately experienced, actively engaged with, deeply reflected on and questioned. By extension, the archives should not be a dusty, little-visited place but vibrant, and actively aiming to build lay appeal in history.

|

The idea of formally setting up an organisation exclusively dedicated to recording and keeping alive the experiences of women originated from a growing sense of dissatisfaction during Lakshmis own work researching the social context of Tamil women writers in the 1960s (it forms the subject of her book The Face Behind the Mask). Archives and libraries contained little information relating directly to the experience of women, and few sources portraying them as individuals in their own right. Thus, any information had to invariably be elicited from alternative sources such as oral history, personal narratives and personal testimony.

Established in 1988 to house the personal collections of such sources acquired by a group of women academics, SPARROW today has a rich and varied holding - oral history recordings, films and documentaries, music records, photographs, advertisements, books, journals, newspaper articles and cartoons, posters, brochures, personal diaries, letters and other memorabilia - that runs into thousands, and is constantly growing. And the journey been one of constant learning and dogged perseverance in the face of widespread scepticism, even derogatory comment. Says Lakshmi, Convincing funding bodies of the sheer necessity and immense value of recording womens experiences and their contributions is a continuous struggle. There are very stereotypical notions at play about what sort of activities non-governmental organisations, in developing countries such as ours, especially with regard to women, should be engaged in, with one government official even denouncing our proposed activities as only collecting chit chat!

But proponents of oral history such as SPARROW argue that such methods are invaluable tools in recovering the experience of marginalised groups such as women or the working class whose voices, by virtue of being absent in official sources, are in the danger of being irretrievably lost. And while oral history has to be treated carefully and subjected to the same scrutiny as any other source, its subjective nature can help understand why individuals remember events the way they do, and the opinions they form.

Though critical of mainstream historiography, Lakshmi clarifies that she doesnt make claims for SPARROWs work to be a definitive representation of the past. The truth, she says, cannot be a legitimate aim for a scholar or student of history. However what we constantly seek to do is to convey a sense of the human experience in its numerous facets and complexity.

![]() As the doyen of oral history Paul Thompson has pointed out, oral history is well suited for this task because it can enable us to go beyond bland and remote generalisations to fascinating personal details that are representative, yet unique. Thus it is one thing for a student to be told in a classroom that women participated in large numbers in the freedom struggle, and quite another to attend a SPARROW workshop and see and hear an octogenarian Gandhian recall with feeling the magic that the Mahatmas words cast over her as a ten year-old girl attending a public meeting, shaping, in the process, the course of her entire life and the values by which it was sought to be led, with little thought of personal gain.

As the doyen of oral history Paul Thompson has pointed out, oral history is well suited for this task because it can enable us to go beyond bland and remote generalisations to fascinating personal details that are representative, yet unique. Thus it is one thing for a student to be told in a classroom that women participated in large numbers in the freedom struggle, and quite another to attend a SPARROW workshop and see and hear an octogenarian Gandhian recall with feeling the magic that the Mahatmas words cast over her as a ten year-old girl attending a public meeting, shaping, in the process, the course of her entire life and the values by which it was sought to be led, with little thought of personal gain.

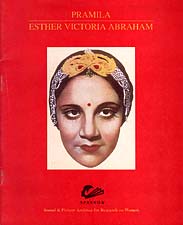

Such interactive oral and visual history workshops aimed at bringing womens narratives centre-stage and stimulating discussion among an invited student audience have been organised with a range of artistes, participants in the freedom struggle and other political movements since, writers and scientists and are followed up with a publication about the life of the women. A biography of social activist Mrinal Gore is the latest in the series of such publications. Mumbais painful experiences of communal violence, and the influence of popular Indian culture and its representation of women have been among other subjects of workshops by SPARROW.

Recounts Lakshmi, It was satisfying to have a young male student come up to us at the end of a three-day workshop exploring Hindi cinemas portrayal of the family and say that from thereon he would accord his younger sister greater respect. If the true purpose of education is to not just stimulate the intellect, but also help develop sensitivity and empathy, then SPARROW seems to be achieving this conscientisation.

However its unconventional activities unfortunately find little place within the confines of mainstream school and university systems. A proposal by SPARROW to various city colleges to conduct a course in oral history - at the end of which students would interview female relatives, collect memorabilia, attempt to write and exhibit a family history in a manner that the whole process of study could be related to their own lives - elicited little interest from the humanities departments. Standard textbooks for undergraduate students of modern Indian history continue to make few and largely generalised references to women, often placing them as objects of reform activity. Most history departments remain highbrow places, favouring a top-down approach, disseminating not knowledge but information.

Yet SPARROW remains convinced of the value of its mission. Panna Roy Chowdhry who has been looking after the organisations Oral History Division for two years now says, My work here is a constant education in that I would otherwise have certainly been ignorant of the stories that deserve a place in our history, yet remain unknown. There is great inspiration to be derived from the struggles and lives of these women, as well as much that I as an individual can relate to. It has certainly taught me to be more assertive, so that working for SPARROW is not just a job but has now become a way of life.

Adds Lakshmi, The most uplifting aspect of our work is the awareness that women trust us with their life stories, which may sometimes include very personal and painful aspects, or some private belonging, with the faith that SPARROW will accord such material the respect that it deserves and see over its appropriate use in any future research. It is a privilege but also an immensely humbling experience.

But there is an acute sense that only a small beginning has been made. I will consider myself to have been successful when I am able to secure a permanent place for SPARROW, says Lakshmi, but only half-jokingly; since its formation she has seen the organisation operate out of her bedroom and a rented garage among other places. Moving establishment with so many holdings can hardly be easy. Currently this veritable goldmine of history is housed in a seemingly innocuous apartment rented in suburban Mumbai, where the SPARROW team carries out its work with the help of private donations and a grant from the Dutch agency, HIVOS. Opening up the archives for access and consultation - at the moment possible only through individual requests, and a limited showcasing of material online - will also be possible when a comfortable nest has been secured for SPARROW.

| SPARROW B - 32, Jeet Nagar, J. P. Road, Versova, Mumbai 400061. Phone: 28245958, 28268575, 26328143 sparrow@bom3.vsnl.net.in www.sparrowonline.org |

The organisation also has an ambitious vision for the future, which includes plans of developing SPARROW as a one-stop access for woman-related research through collaboration with libraries all over the country and acquiring from them copies of relevant material; the setting up of an interactive multimedia museum and a FM radio station to broadcast history in creative and engaging ways. The increasingly homogenised images of women in the mainstream media and the values they propagate are distressing. We would like to create an alternative public space for the understanding of womens experiences and contribution, says Lakshmi.

Meanwhile a group of twenty-odd dedicated individuals cheerfully work away at keeping alive certain voices from the past, as well as those from the present that are often muted. In doing so, they raise the crucial questions: what is history, and who are its worthy subjects?