It is most often an unaddressed issue in the public discourse over the quality of life in urban India but many of the challenges faced by our cities and towns today can actually be traced back to inadequate and unskilled staffing in city governments.

The lack of efficient hands on board results in a vicious cycle wherein urban local bodies are ill-equipped to raise adequate revenue, which in turn results in a shortage of funds to undertake infrastructure development and service delivery. This ultimately leaves citizens to grapple with day-to-day inefficiencies such as poor public healthcare and education systems, faulty drainage networks and badly planned roads.

Data from some of India’s largest municipal corporations speaks volumes about the sorry shape of India’s urban local bodies. The municipal corporation of Bangalore which manages an estimated budget of Rs 9,729 crores has no inkling of how many staffers it employs.

The nation’s political capital, Delhi has only 1,260 civic employees per 100,000 population. And rules that were drafted in the pre-Independence era define staffing patterns in municipal corporations across Punjab, even today.

The human resource crunch

The 74th Constitutional Amendment Act (CAA), 1992 envisaged creating self-sufficient urban local bodies that would be empowered with funds, functions and functionaries. Government committees and urban experts analysing the functioning of urban local bodies have time and again waved the red flag about the poor staff capacity of city governments.

The neglect of urban capacity building has been addressed by the Second Administrative Reforms Commission, the 11th Five Year Plan, the High Powered Expert Committee on Urban Infrastructure, and the Working Group on Capacity Building constituted by the Planning Commission.

“The requirements for capacity building in terms of demand–supply gap are high not only on account of the number of people to be trained but also in terms of the competencies of the personnel required if the intended governance and service delivery standards are to be achieved,” states the report of the Working Group.

A 2010 report by McKinsey Global Institute titled ‘India’s urban awakening: Building inclusive cities, sustaining economic growth’ blamed the lack of local capacity and technical expertise for the inability of cities and states to successfully implement reforms.

More recently, the Annual Survey of India’s City-Systems (ASICS), brought out by Janaagraha Centre for Citizenship and Democracy, analysed 21 cities and found that no city, with the exception of Delhi and Patna, has significant powers to recruit and manage its own staff.

In the other cities, even the head of the civic body, the municipal commissioner has little or no authority to recruit staff or take disciplinary against them, as these crucial functions rest in the hands of the state government.

Moreover, city governments have failed to expand their workforce in keeping with the burgeoning population. Even corporations in better staffed cities such as Delhi and Mumbai pale in comparison to the numbers of their counterparts across the globe. Delhi and Mumbai have 1,260 and 895 employees per 100,000 population respectively vis-a-vis New York’s 5,338, London’s 2,961 and Durban’s 3,109 per 100,000 population respectively. The ratios are even worse in smaller Indian cities.

Worryingly, these figures are the ones reflected on civic records and don’t factor in the posts that are lying vacant. In Bangalore for instance, 8,955 of the 19,201 permanent posts sanctioned in the Bruhat Bangalore Mahanagara Palike are lying vacant.

The colossal mess in which staff structures in municipal corporations rest is evident from the fact that not a single corporation among the 21 cities analysed puts out its staffing data in the public domain in a manner that comprehensively defines a break-up of sanctioned versus working employees or grades to which the staffers belong.

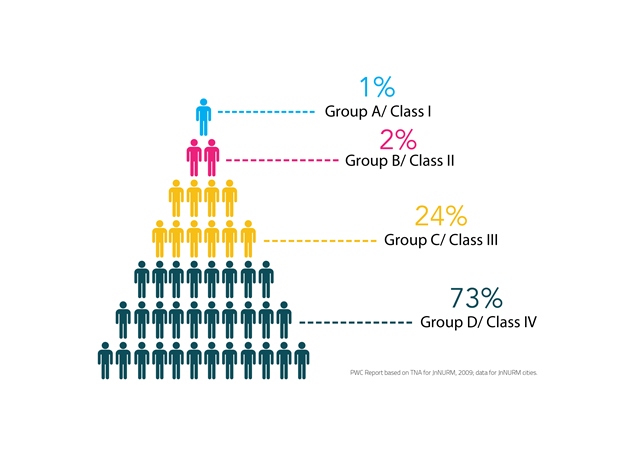

This level of detailing in staffing patterns is important as the shortfall in the number of civic employees is complemented by the mismatched or missing skill sets of employees. A 2009 PricewaterhouseCoopers report titled “Capacity Building of ULBs: An urgent imperative” found that an average municipal corporation of 20,000 employees had 200 Group A employees vis-à-vis 14,600 Group D staffers.

In other words, the staffing of an average municipal corporation was highly lopsided with an acute shortage of senior management personnel. There were merely 3 per cent Class I and II employees, with most of the organisation filled with functional posts such as clerks, drivers and timekeepers.

Unfortunately, there is no well-defined or standardised set of functions or job descriptions for urban services, across cities, that could serve as a manual to ensure that corporations are correctly staffed.

Illustration courtesy: ASICS, Janaagraha

Destination Organisation Charts

So, what is the way out? The report of the Working Group recommends that every urban local body should prepare a capacity building action plan taking into account its local circumstances and challenges.

Urban capacity building efforts undertaken till now have however, lacked strategic interventions to tackle the quality and quantity problems of urban staffing, largely being restricted to training sessions and creation of institutions. The Centre has allocated approximately Rs 1,938 since the period of the Eleventh Plan towards these trainings and institutions but the ineffectiveness of such measures is evident from the poor outcomes.

One such strategic intervention needed is a mapping exercise of existing staff in municipal corporations, as is the practice in most companies. Let’s call this exercise creating destination organisation charts. It essentially involves identifying the number of staff currently working in a municipal corporation, estimating what the ideal staff strength should be proportionate to a city’s population and target delivery standards, and drawing up a roadmap to bridge the gaps.

Destination organisation charts would also involve defining the skill sets of employees at every level of the municipal organisation to ensure that staffers are best fitted to roles that match their qualifications and skills.

There is no denying however, that every city and city administration has unique needs and resource constraints. To be most effective, urban local bodies should thus be incentivised to create their own destination organisation charts. Such mapping also has the potential to throw up a whole new segment of jobs in the urban sector.

One such exercise undertaken by Janaagraha threw up many surprises. An exhaustive mapping of the Bangalore municipal corporation showed for instance, that Bangalore on a conservative basis requires 27,210 employee posts (including contracted pourakarmikas) to efficiently service its population as compared to the 19,201 that are currently sanctioned.

The corporation also requires significant strengthening of its general administration staff to meet the dynamic requirements of information technology, human resources, public relations and welfare among other evolving functions. The engineering department, too, needs a significant boost in order to strengthen the town planning as well as mechanical and electrical functions. Destination organisation charts recommend a multi-pronged approach for easing hiring norms, lateral hiring and outsourcing to resolve the existing gaps.

There is no denying however, that destination organisation charts cannot operate in isolation. There needs to be a larger ecosystem geared towards urban capacity building that would begin with better devolution of powers to the municipal level.

Instituting a specialised profession of urban managers by way of municipal cadres to provide a skilled pool of human resources with clearly defined career progression frameworks might be a good start. Only Bhopal, Patna and Kolkata are currently covered by such an arrangement. Cadre rules that date back to the 1940s and 1950s in many cases also require urgent updating.

The redefining of organisational structures would also need to be matched with adequate financial resources. While an exact estimated investment is tough to project, the Working Group proposed an overall allocation of approximately Rs. 13,000 crore during the 12th plan period towards urban capacity building.

Such a holistic approach could breathe fresh life into India’s ailing municipal corporations. It is imperative for municipal organisations to break away from their age-old employment norms if they are to improve the quality of infrastructure and services they provide to their citizens.