Garbo Murmu, 55, and his wife Muni Hajda, 45, an adivasi couple of Gosaigaon sub-division in Kokrajhar district in lower Assam were brutally tortured with sharp weapons by attackers from their own community on the night of 18 October 2009. The attackers, who branded them a witch-couple, entered their house when they was asleep inside their hovel at the Ramendrapur relief camp. After attacking them for about half an hour, the mob, assuming that their victims had succumbed to injuries, left them and fled from the spot taking cover of darkness.

The couple was, however, fortunate enough and survived to tell the tale of their return from the jaws of death. Next morning the local unit of Birsa Commando Force (BCF), a militant organisation fighting for rights of Adivasi people in Assam - currently in a ceasefire agreement with the government - found them lying unconscious in a pool of blood on the bed, rescued and arranged a car to rush them to Kokrajhar Civil hospital, which is 60 km away from the camp area.

The injuries and cut marks on Garbo's face and head were so deep that initially the doctors were unsure how to administer the oxygen which he needed desperately. The mob which had attacked him had also completely disfigured his wife Muni's face. Ten days after the attack, she could still not speak. Still recovering in the hospital from his trauma and injuries, Garbo could not walk, but with much difficulty and determination, he narrated the sorrowful tale of how he and his wife came to be branded as witches.

The injuries and cut marks on Garbo's face and head were so deep that initially the doctors were unsure how to administer the oxygen which he needed. (Above: Picture of Garbo in hospital.)

But, for the same reason they were also under threat. Land mafias with an eye on the camp site were threatening displaced families to move from the camp site. "We have been facing threats from various persons to vacate the land we have occupied in the camp. However, all of us have decided not to leave the place," says Garbo.

But the family's resistance would be challenged from an unexpected quarter. To their perplexion and horror, they were branded daina (a local word that means 'witch'). "Perhaps, these people thought that branding us daina and killing us would frighten the other families in the camp site, and they will vacate the place," Garbo said.

During their prolonged stay in the hospital, barring a few relatives, no police personnel or persons from any social organisations made any visit to know about their conditions, he alleged. His son Raga, however told India Together a case had been registered in Kachugaon police station by the local cadres of BCF.

Other victims

Garbo and Muni were not the first victims of such assault; indeed, they were fortunate to be still alive. Unlike this Adivasi couple, however, Bishnu Rabha and Purshee Rabha - who belonged to the Rabha tribe in Rajapara village of Palashbari in lower Assam's Kamrup district - were not so lucky. The elderly couple, already crossed their sixties, lived as quacks in the village. Similarly branded as witches, they were burnt alive in daylight by their fellow villagers on 5 September this year. The villagers also made one of their sons to witness the brutal act, while the other son fled for fear of his own death.

The couple's neighbour Banti Rabha, with whom they'd been involved in a land dispute, had committed suicide due to some unknown reasons. Since then, Banti's widow claimed she had begun having nightmares, and accused the couple of being responsible for her horrifying dreams. The accusations finally landed Bishnu and Purshee in front of a village court. As it turned out, this would prove to be a kangaroo court. Going by the widowed woman's word, the villagers recalled a number of earlier instances where they found that whoever had some misunderstanding or dispute with Bishnu and Purshee had died unnaturally.

The village court's puinishment was severe and swift - they were to be burned alive, for practising witchcraft.

Significantly, in an another incident a day later in Lohit-Khablu Panchayat under Panigaon police station of Upper Assam's Lakhimpur district, Rajen Pegu, the president of the Managing Committee of Kambanggaon Primary School was killed in his sleep. He too had been accused of practising witchcraft.

Witch hunting in Assam

The state police do not register witch-hunt deaths and assaults separately; instead these are treated as routine cases of 'murder' or 'attempt to murder'. Morevoer, instances of expulsion of suspected dainas from a village are not even recorded; only serious crimes involving bodily harm are documented. It is therefore impossible to collect information on the number of persons who have been killed due to suspicion of practicing black magic or witch craft.

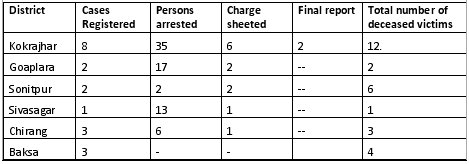

Cases related to witch-craft in Assam, 2006-7

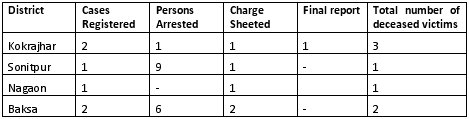

Cases related to witch-craft in Assam, 2007-8

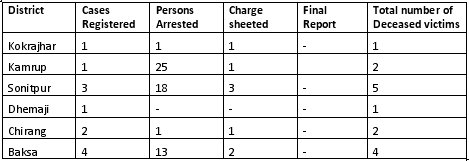

Cases related to witch-craft in Assam, 2008-9 (up to September)

While the state police fail to provide accurate data, local newspapers, to some extent reveal the actual situation by focusing on incidents. The local dailies in Assam published four incidents of witch hunting in September and two in October last year. These incidents took the lives of six persons, while three others survived assaults by locals. But here too there are shortcomings; even the media is interested only in sensational cases, relating to murder or attempted murder, and make little or no mention of expulsions.

Along with the increasing in number, witch hunting incidents in the state are also becoming more complex. Originally, incidents were limited to tribes meting out public punishments to those charged with practising black magic. Today, witch hunting cases often relate to personal rivalry, grabbing property or land, and other divisive issues, apart from mere superstition. There is also a trend of killing the suspected persons secretly, preferably at night, taking advantages of darkness, so that no one can identify the culprits.

Also, in the past only women were vulnerable to be attacked as witches in traditional societies, but of late the attacks are focused on entire families, even if only one member is accused. Five members of a family in Sadharu tea estate in Biswanath Chariali of Sonitpur district in upper Assam were beheaded by their fellow villagers in March 2006. The hysteric mob then marched to the police station carrying the severed heads of the deceased persons. Again, on 10 June 2008 four persons of a family under the Biswanath Chariali police station of the district were buried by the locals, on the suspicion of witchcraft.

These incidents take place where there is severe lack in basic infrastructure including healthcare, education, sanitation, road network, drinking-water and others. But it is not only the disadvantaged and poor who have been targeted. In September 2008, Bishnu Roy the senior most leader of North Salmara district of Koch-Rajbangshi Yova-Chatra Sanmilani, and his mother, in Abhayapuri police station of Bangaigaon district were targeted and attacked by a mob of 500-600 villagers on the suspicion of being witches.

Upen Rabha Hakasam, a Professor at the Department of Folklore in Gauhati University (he is himself a Rabha tribal) has been fighting against the harmful practice over the years. Some of his relatives too have become victims of suspicion of practicing witchcraft or black magic. "I have been fighting against this social evil in our tribe for so many years, but there is hardly any change. The custom is been deep rooted in the minds of the people. Unless there is a change in the policy framework no one can do anything. I believe victims of witch-practices themselves must come to the streets to assert their right for a dignified life, in the way the sex-workers and homosexuals have done already."

"Until and unless these victims themselves come to the street, I believe nothing will change, and the vested interested people will always take the chance of their helplessness," Hakasam adds. He says the lives of those facing expulsion from their villages has become miserable, as they have to move to remote areas to escape the stigma - their 'witch' brand spreads very fast to nearby areas. In those places too, where these victims find new livelihoods, they have to hide their identity for fear of the past catching up with them again.

Hakasam says that the low socio-economic status of these tribes and communities in the state is a major reason why such practices continue. But he also blames the willingness of people to believe such accusations, and this is not just among the poor. "It is surprising that even a section of the educated people of these tribes and communities still believes such superstition, like the existence of witches. Also, as some kind of religious practices have been attached to the belief, it becomes difficult for outside agencies or individuals to intervene in such situations and motivate them against such social evils", he adds.

ABSU campaigns against witch hunting

This is one reason why, even as incidents of witch-hunting have been increasing, there aren't very many organisations working to tackle the practice. Instead, it has been left to national organisations and other platforms to do what they can. The All Bodo Students Union (ABSU), the apex student body of the Bodos, has launched a vigorous awareness campaign to fight against superstition of witch-practices in the Bodo-dominated areas. The ABSU, which has been running the campaign since 2004, has so far rehabilitated at least 40 innocent persons who have been expelled from their original villages on the suspicion of witch practices, says Lawrence Islary, a senior leader of the student body.

Muni Hajda in hospital, following the attack on her.

Muni Hajda in hospital, following the attack on her.

Islary says that improvement of basic healthcare and education in these areas may improve the situation to a great extent. Unfortunately, both healthcare and education infrastructure is very poor in all tribal-dominated areas in the state, he observes. "For instance, in Parbatjhara sub-division of Kokrajhara district, there was hardly a doctor last year and even now there is only one MBBS doctor to look after a huge population," he adds.

Absence of doctors is directly related to the problem - villagers and tribes are compelled to visit local quacks for treatment of different diseases. During monsoons in particular, water-borne diseases like malaria, cholera, and diarrhea often takes an epidemic form in villages. If the treatment is beyond their limit, these quacks, just to remain on safe side, accuse someone of the village of being a witch and declare that the bad spirit of that particular witch is responsible for diseases and deaths in the village! Such pronouncements and the prevailing superstitious beliefs in witchcraft provoke ignorant villagers to target their own neighbours and acquaintances.

In non-Bodo areas, there has been less progress against superstition and crimes linked to it. Clearly, a lot more is needed to be done, across the state, to have a significant impact.

More needed from the state

Hakasam is also critical of the role the state government has played - or more accurately, not plated. There has been so serious effort to punish the culprits, nor is there usually a proper investigation into incidents. In many witch-hunting related cases, the culprits are easily identifiable, or in many cases they themselves admit their guilt. But seious punishment for such crimes is rare. This has encouraged the vested interests, aggravating the situation, he says. Unlike Bihar or Jharkhand, in Assam there is no legislation to deal with the situation, despite the increasing incidents of witch hunting."