On 8 January, 2016, the Government of Chhattisgarh (GoC) passed an order cancelling the community forest rights of the tribals of the village of Ghatbara, which had been granted to them several years back under the Forest Rights Act. Even as the affected communities and legal experts question the legality of the state government’s action, there is another aspect that makes the order significant. The GoC has annulled the tribals’ rights because, it says, these were being used by the tribals to oppose mining of coal in the region. But the people have good reasons for doing so.

Coal mines and Hasdeo Arand

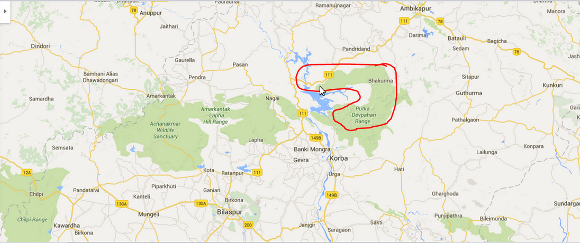

At the heart of the debate is the region known as Hasdeo Arand (or Hasdeo Aranya – Hasdeo forest). This area lies in the upper part of the catchment of the Hasdeo river, an important tributary of the Mahanadi. Hasdeo Arand has some of the finest forests in central India, but also huge coal deposits. In fact, several other parts of the Hasdeo basin too have coal deposits, and the Korba region in the middle of the basin has some of India’s largest coal mines, and associated industries such as thermal power plants.

Hasdeo Arand coal block. The reservoir adjoining the region is the Hasdeo Bango Minamata reservoir. Pic: Google

The Hasdeo Arand region with its very rich forests and biodiversity, was marked as a ‘No-go’ area in the proposed ‘Go/ No-Go’ classification which specified forest areas where no mining would be permitted.

In spite of this categorisation, on 23 June 2011, Shri Jairam Ramesh, then Minister of State for Environment and Forests, accorded forest clearance to mine the Tara, Parsa East and Kante Basan coal blocks in a speaking order. The coal blocks were allotted to the Rajasthan Government for its power utility Rajasthan Vidyut Utpadan Nigam Limited (RVUNL). The actual mining is done by a company of the Adani group, as a mine developer and operator.

Parsa Coal Mines. Pic: Shripad Dharmadhikary

As mining began in the Parsa, Kante, Basan blocks, local communities started reeling under the many adverse impacts of the mines. The callous attitude of the mine operators and the utter neglect and disregard by the authorities made matters worse. During a recent visit to the area by this author, local people complained that mining had ruined their lands and their water. They said that dust had become a big health menace.

“Our entire lands are coated with dust. In the rains, this dust is washed into the fields. The crop production on our lands has also gone down as a result,” said one of the villagers in Salhi village, next to the areas where mining is going on. They also pointed out that ongoing mining had severely affected their groundwater, levels of which had fallen sharply.

It may be noted that mining, particularly open cast mining, is equivalent to digging a huge pit, and this pit can draw in groundwater from surrounding areas. In Parsa village, where people used to get two crops a year, the groundwater levels have dropped and they are barely able to get one crop. The heavy truck movement – one villager estimated that close to 700 trucks went past the village every day – has not only added to the dust, but has also resulted in a number of accidents injuring local people.

Fields near Parsa Mines in Parsa Village affected by falling groundwater levels. Pic: Shripad Dharmadhikary

However, the most serious of all problems has been the contamination of the local water sources, including several nallahs (streams) in which clear and clean water used to flow. The mines started discharging the contaminated mine discharge water directly into the stream, particularly the Ghatbarra nallah. This pollutant and sediment-laden water has rendered the stream unusable for the people, and their cattle.

The fish – which aided the people’s sustenance in a big way – have been affected too. The people started protesting, but their pleas fell on deaf ears. In a major accident, some 14 cattle died in one of the nallahs due to polluted water. It was only after long protests, and when people complained to the local Forest Officer at Ambikapur, that the officer conducted some enquires and forced the mining company to stop the discharge.

The impact on the Ghatbarra nallah has been so bad, that even the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEFCC) has had to take notice. Adani Enterprises Limited has now proposed to set up a 270-MW thermal power plant in the same mining area, a coal washery reject-based power plant. While considering its application for extension of the time period for submission of the Environment Impact Assessment and public hearing, the MoEF’s Expert Appraisal Committee, in its 50th meeting held on 28-29 Jan 2016, put a condition on the company that “the Barra nalla shall be restored to its original state.”

During my visit, I too witnessed the huge dust pollution in the area as well as the pollution of the nallahs.

Dengur nallah or Kesla river, in Korba, showing polluted water. Pic: Shripad Dharmadhikary

Given all this, there is little wonder that the local people have become fed up with the mines – the atyachar (atrocity) of the mines, as they put it. And they are apprehensive that if this is the situation with just a couple of operational mines, what would happen when many of the other proposed mines start operations in the area? So, they have declared that they do not want the mines at all. They have formed the Hasdeo Aranya Bachao Sangharsh Samiti to save the villages, and 22 village gram sabhas have passed resolutions that they don’t want the mines.

If one delves deeper, it will be realised that it’s not just their own experience that is making them staunchly opposed to mining in the region. The people have also seen what has happened in Korba, just 100 kilometres downstream from Hasdeo Arand.

Korba – A critically polluted region

Korba is called the power hub of Chhattisgarh, and sometimes even of the country. It has huge coal mines like the Gevra – the largest open cast coal mine in Asia, Dipka and Kusmunda. It has many thermal power stations, including those belonging to the NTPC, to the Chhatisgarh State and several private ones as well.

Dried coal ash in a ash pond near Korba.This ash is blown by the wind resulting in a dust menace. Pic: Shripad Dharmadhikary

In 1967, a barrage was built on the Hasdeo river to supply water to the industries. In early 1990, the Hasdeo Bango Minamata dam was completed upstream of the barrage. These power plants along with iron and steel industries are drawing huge quantities of water and dumping waste water in the local water bodies, nallahs and even major tributaries of the Hasdeo like the Ahiran. Vast areas of land have been taken over for dumping ash slurry from the coal power plants. The combined impact of coal dust and ash has led to the dust menace in Korba city.

In 2009, the MoEFCC carried out a survey of 88 industrial clusters in India for a Comprehensive Environmental Pollution Index, and Korba was found to be the fifth most polluted in the country. It was declared a “Critically Polluted Area”. In 2013, it was removed from this list, but even officially, the improvement was marginal and Korba remains a highly polluted region to date.

As a large number of coal mines, followed by power plants, are lined up in Hasdeo Arand, the people there see in Korba a frightening picture of their own future. This has further strengthened their determination to say no to the proposed coal plants.

Ironically, it’s not only the local people who are saying no to the coal plants, but even the MoEFCC itself had – at least at one time – ruled against any further mining in the Hasdeo Arand area.

Coal ash and other pollutants seen in Ahiran river, a major tributary of Hasdeo, near Korba. Pic: Shripad Dharmadhikary

MoEF’s objection to mining in Hasdeo Arand

As noted earlier, in June 2011, Jairam Ramesh had given clearance for mining in Tara, Parsa East and Kante-Basan blocks. In his speaking order, the Minister himself noted that the Forest Advisory Committee had earlier rejected this permission three times, and it was their fourth rejection that he was overruling to grant clearance. Thus, it was clear that even then, the Ministry had recognised the immense environmental value of the Hasdeo Arand forests and was reluctant to give permission for coal mining.

Further, even though permission was granted in June 2011, the Minister made it absolutely and unambiguously clear that this permission was being given only as an exception, and that “as long as the state government does not come up with fresh applications for opening up the main Hasdeo Arand area, I am of the opinion that permission can be accorded for Tara, Parsa East and Kante Basan blocks.”

Yet, now that the permission has been obtained and mining started in these areas, there are proposals to start mining in many more areas of the Hasdeo Arand, in complete violation of this explicitly stated order.

Such steps clearly lead to a loss of faith in the regulatory mechanisms, and constitute one of the reasons why the people are feeling so threatened by mining. These pose a clear signal that the MoEFCC may impose many conditions to push through clearances for the time being, but subsequently will not hesitate to backtrack on such conditions.

The final analysis

Thus, it is clear that the decision of the people of the Hasdeo Arand region to question coal mining in the area is based on their own experience as well as the terrible conditions at Korba. They have been legitimately using the rights available to them under the Forests Rights Act, and other laws of the land to raise these very important questions.

To stifle these questions by arbitrary annulment of people’s rights is nothing short of use of force to stop protests. Instead, the Government needs to understand the issues being raised by the people, and provide answers to them, not just through words, but through action that will address their questions and grievances in a meaningful manner. Only then can the people’s faith be restored in the intention and ability of the government to avoid a social and ecological disaster in the area.

Till then, people are likely to continue to challenge the spectre of what they see as the transformation of some of India’s best forests into one more critically polluted area.