In her captivating documentary film Invoking Justice, the seasoned and acclaimed film maker Deepa Dhanraj, portrays how the Muslim Women’s Jamaat functioning in Pudukottai district in Tamil Nadu assists women to secure redressal under the Sharia law, for the violence and injustice they face. Many of these women survive extreme partner violence, severe marital disputes, sexual or other harassment, privately or publicly.

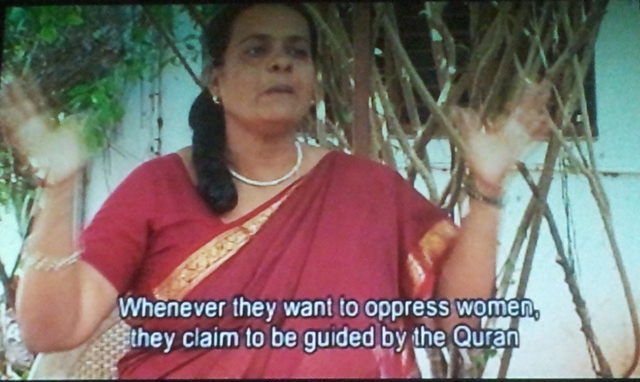

The film shows how almost no woman obtained justice under the Sharia law through the regular Jamaat, which is comprised of and controlled by men. Obviously, these men who are fairly regressive in their views about women, pronounce verdicts against the interests of the woman, even where the man is wrong. Further, men reinterpret the Quran according to their patriarchal notions and use it to suppress Muslim women and deny them their basic rights.

At present, three laws govern Muslims in India namely, the Muslim Personal Law (Shariah) Application Act 1937, the Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act 1939 and the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act 1986. The first simply states that Muslims will be governed by their Personal Law, while the second permits a Muslim woman to seek dissolution of her marriage on nine different grounds.

The third legislation was passed after the famous Shah Bano case, when the government gave in to the demand of the predominantly male and patriarchal Muslim leadership in India that objected to Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code (Cr. P. C.) being applied to Muslim women in India, as it was considered interference in the religious matters of Muslims. The Act denied divorced Muslim women the right to claim maintenance from their former husbands, previously available to them under the aforementioned section.

A still from the documentary, Invoking Justice. Pic: Pushpa Achanta

“We are all Muslim women, practising Islam since childhood. We set up a Jamaat for women when we observed that it is almost impossible for women to resolve their domestic challenges under the Sharia law, favourably, through male dominated institutions. Additionally, only a few aggrieved women seek justice legally either because they are unaware, cannot afford it socio-economically or cannot obtain a remedy, as is the case with most women in distress, whatever their religion or caste,” shares Sharifa Khanum, the founder and active member of the Tamil Nadu Muslim Women Jamaat, in the film.

Throughout this powerful yet moving production, members of the women’s Jamaat or other Muslim women who have approached it for justice recount their stories directly. A lady whose daughter was burned to death by her in laws gets moral support from the Jamaat although the perpetrators remain unpunished. Contrastingly, the calm yet determined Fatima (name changed) the first lady to separate from her abusive husband through the women’s Jamaat returns home with her adolescent daughter, relieved.

Reimagining the law

In fact, it is not just the Muslim Women’s Jamaat that is resisting the gender imbalance perpetuated by Sharia law. Several other organisations and initiatives across the country, some more institutionalised than others, have come to the aid of wronged or victimised women from the community in various ways.

Launched in 2007 as a movement to assist Muslim women, the Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan (BMMA) spread nationwide and has chapters in different states. Apart from handling marital and domestic disputes of women, it conducts training programmes for women on leadership and provides awareness on laws, basic rights and social entitlements, and ways to avail them. The committed and cheerful women in BMMA’s Mumbai office are among those who contributed to the draft codification of the Sharia law released in June 2014, which favours Muslim women.

Workers at the Mumbai office of the Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan. Pic: Pushpa Achanta

Noorjehan Safia Niaz, the courageous co-founder of BMMA and a writer and human rights activist aged 44, who has completed her doctorate in sociology, said, “Before proposing changes in the Sharia law, we consulted Muslim women across different socio-economic groups throughout India. Women from disadvantaged financial classes demanded monogamy, attainment of adulthood for girls and boys before marriage and registration of marriage and payment of maintenance after divorce. This is because such women suffer most due to the Sharia law allowing Muslim men to practice polygamy, triple talaq, etc”.

Further to the above, the highlights of the draft are as follows.

For the solemnization of marriage, the parties must approach a registered qazi with an application 30 days prior. The actual procedure includes the ijaab [proposal] and qubool [acceptance] in a single setting followed by the filling up of the nikaahnama which contains basic details and signatures of the qazi, the bride, groom and the witnesses.

The responsibilities of the qazi include ensuring the conditions mentioned above before solemnization of marriage and demanding authentic proofs pertaining to the date of birth and the place of residence of the parties. The qazi must also maintain proper record of marriage and give duly certified true copies of the nikahnama to both parties.

The minimum mehr should not be less than the groom’s entire annual income for one year and can be given either in cash/gold/kind. If determining the mehr in this manner proves to be difficult, then it can be decided based on the minimum wages of that location and the occupation of the groom. The mehr must be given to the bride at the time of the marriage and is the wife’s exclusive property. It is illegal to compel or emotionally pressure a wife into foregoing or returning the mehr amount.

Three forms of separation between the husband and the wife, namely, khula [demand for divorce by wife], talaak [demand for divorce from husband] and mubarah [divorce by mutual consent] are recognised. Irrespective of who raises the demand for divorce, the method of divorce would be the talaak-e-Ahsan method which is a divorce over a period of three months with intermittent attempts at reconciliation by the parties and their families. Any other method of divorce is invalid.

The practice of halala, where a divorced woman must compulsorily marry another man if she or her previous husband or both want to reunite matrimonially, is an offence. Halala is not only unQuranic but also has been used to force a woman to lead an undignified life.

A marriage is deemed irregular if two adult witnesses are not present at the time of nikaah, if the marriage has been solemnised during the period of iddat or without the qazi, if the marriage is not registered as mentioned and if the amount of Mehr as specified is not paid. An irregular marriage can be regularised within one year of the solemnisation of marriage. The rights of women and children are not affected if the marriage is not regularised.

Marriage solemnised under this Act will be invalid if the consent of either party has been obtained by force, coercion, undue influence or fraud. Any children borne out of either irregular or void marriage are deemed legitimate.

The husband must provide maintenance (even during arbitration) which includes food, clothing, housing, educational, medical and personal expenses, even if his wife has an independent source of income. If the custody of a child is with the mother, the responsibility of maintenance of the child is with the husband.

According to Noorjehan, Islamic countries like Pakistan and Bangladesh have laws safeguarding the interests of Muslim women in marriage and divorce. As no such codified legislation exists in India, the Sharia drafted by the BMMA aims to ensure justice for Muslim women during marriage and divorce. However, this is possible only if the draft becomes a law for which it must be placed before the Indian Parliament. Hence, the BMMA is now working to garner larger support for the draft.

Empowering Muslim women

The Mumbai office of the BMMA is strategically located in the socio-economically marginalised Muslim traders’ hub of Kherwadi road in Bandra. Unsurprisingly, the riots of 1993 adversely impacted such disadvantaged Muslims and men, particularly. Further, many Muslim men from the area have been falsely implicated after incidents of communal violence and bomb blasts over the last two decades.

“Incidents following the riots led women in the Muslim community to assume responsibility of their households and safeguard the men in their families from being penalised wrongly in different cases. These women also started interacting with people outside their families and communities for perhaps the first time in their lives. When we realized that Muslim women had minimal awareness of their rights and entitlements and the law, we began to conduct training sessions for them,” revealed 57-year-old Khatun Shaikh, the outspoken co-founder of Mahila Shakti Mandals and an active member of the BMMA. Interestingly, some members of the Mahila Shakti Mandals are not Muslim women.

Khatun Shaikh, co-founder of Mahila Shakti Mandals and an active member of the BMMA, Mumbai chapter. Pic: Pushpa Achanta

Khatun explains, “Married Muslim women also understood that many of the husbands are encouraged by Sharia law to divorce their wives at will and pay little or no maintenance. The trained women now started to share their knowledge with other women and also used it for mediation in family and marital disputes. That initiated the formation of Mahila Shakti Mandals in different neighbourhoods in areas such as Bandra and Dadar. They also spread to Osmanabad, Nashik, Pune and Ahmednagar.”

Other initiatives

An outcome of the Mahila Shakti Mandals described above, are the Sharia Adalats (court under the Sharia law) which exist in a few states, namely, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Gujarat, at present. This is a sort of paralegal structure which offers mediation and marital or domestic dispute resolution services, particularly for Muslim women. It operates with women as the primary members and negotiators of justice for Muslim women.

In similar efforts, Muslim women working with Vimochana – a reputed 35-year-old forum for women’s rights in Bangalore – initiated the Apa ki Adalat (Apa means older sister in Urdu), an informal yet accepted set up that has been ensuring that Muslim women get justice, especially in case of marital and domestic tussles.

To its credit, Apa ki Adalat has been able to garner the support of some of the progressive Muslim men including those associated with the running of mosques or performance of religious rituals.

Tanzeen, one of the key members of Apa ki Adalat, says, “Muslim women are not aware of the law or their rights. Even if they are, very few of them speak up about the gender abuse and injustice that they experience at the hands of men in their families due to fear, diffidence, exaggerated and oppressive notions of family honour and the like. Through the periodically convened Apa ki Adalat, we try to resolve their problems through mediation and counselling, especially of the men. This system has been successful to a large extent in securing justice for our women”.

There are, of course, critiques of the BMMA draft Sharia law, especially regarding the polygamy clause. Other revolutionary efforts described in this article too, may not serve all Muslim women even in the immediate physical vicinity. Institutions such as the All India Muslim Women’s Personal Law Board are busy pursuing their own activities. Nevertheless, all of these are crucial steps to ensure the dignity, rights and individuality of Muslim women.

REFERENCES

1. Laws Governing the Muslim Community, Noorjehan Safia Niaz; April 2003, Women’s Research and Action Group

2. My Struggle My Leadership, Report of Legal Aid Services by Mahila Shakti Mandal; June 2012, Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan

3. Codification of Muslim Family Law in India-An Initiative of Indian Muslim Women