The preoccupation with providing residential and commercial real estate in this country's cities has led to the severe neglect of open spaces. While finding a roof over one's head is admittedly a priority, the shrinking of parks and recreation grounds is already depriving millions of children in urban areas of anywhere to play. It hardly needs to be stressed that this will cause both physical and psychological damage: play teaches children to socialise at an early age. In the absence of playgrounds, children will remain inward-looking and find it difficult to interact with their peers as they grow older.

It may come as a surprise to many to learn that among India's major cities, Gandhinagar today has the most green space, as much as 160 sq metres per inhabitant. Admittedly, Gandhinagar, adjacent to Ahmedabad, has a small population - just under 0.3 million in 2011. Chandigarh follows with 55 sq metres. Being planned cities, the ratio of open space to population is much larger in these two state capitals than even in the "garden city" of Bangalore.

By 2005, the new capital of Gujarat had an area of about 57 sq km, with a tree cover of 57 per cent - comprising almost 33 sq km. Since figures from the 2011 census are not readily available, the position of different cities in 2001 shows that after these two new capitals, Delhi figured third with nearly 300 sq km of forest and tree cover, amounting to 22 sq metres per inhabitant. Remarkably, Delhi increased its tree cover over the previous decade ten-fold.

Bangalore was fourth, with 19 sq metres per person. It has some 705 parks and gardens and another 200 grounds waiting to be converted into these. However, most of the species of trees planted are exotic, which does not bode well for their sustainability.

Mumbai must figure as the city with the lowest ratio in the world, at least among mega cities with over 10 million people each. Each Mumbaikar has only 1.1 sq metres, which may only half in jest lead to a mutation of this city's human species in the decades to come. In 2000, London had 32 sq metres, New York 26 and Tokyo 4 sq metres per person. The 22 largest Dutch cities have almost a fifth of green cover, amounting to an astonishing 228 sq metres per inhabitant. Canberra and Greater Paris record 80 sq metres per capita.

The worldwide norm is said to be 20 sq metres per head which translates to 1.25 hectares or 3 acres for every thousand residents. What is more, access to open space ought to be 250 metres from one's residence and, if ecological considerations have to be taken into account, trees planted in such spaces should be native varieties, to ensure the greatest amount of biodiversity.

Mumbai trails behind Indian and other cities with an abysmal 0.03 acres for every thousand residents. Hardly a day passes without mention of yet another scam involving the few remaining open spaces. Film-maker Subash Ghai is being forced to return the land where he has established a film school known as Whistling Woods. The name is appropriate, because it is part of the state government's Film City, carved out from the Sanjay Gandhi National Park. Indeed, this is the one large green area - 130 sq km, though only 50 sq km lie in Greater Mumbai, with the remaining area in the adjoining metropolitan region in Thane - which the metropolis can boast of. Greater Mumbai, the city proper, is officially 466 sq km.

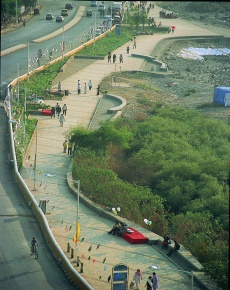

Public promenades built a little over a decade ago in Bandra now serve as cultural spaces, apart from recreation. (Pic Credit: P K Das).

•

Port Trust in the dock

•

Is remaking Mumbai sustainable?

•

Pie in the planning sky

An innovative new approach to Mumbai's open spaces is an extensive mapping survey conducted by the architect and activist, P.K. Das. These maps are currently displayed over three floors of the National Gallery of Modern Art as the "Open Mumbai" exhibition. Next month, it will transfer to the Nehru Centre. The Mumbai Waterfronts Centre (of which I am a Trustee) has co-hosted the exhibition with Das' architectural firm. It was opened by Chief Minister Prithviraj Chauhan and visited by Sharad Pawar and Sena leader Uddhav Thackeray, whose party rules the corporation. MPs and corporators are asking for their ward-wise "re-envisioning" maps and action plans.

To everyone's surprise, the survey establishes the area of Greater Mumbai as 487 sq km, a full 21 sq km more than commonly estimated. Presumably this has to do with what is being measured. Rather than take conventional open space - which are gardens, recreation grounds and playgrounds - this survey also looks at various natural assets. Probably a better term is an area which is "non-buildable", or at least, given Mumbai's proclivity to build on every inch of land, which ought to be non-buildable.

Thus mangroves, which have probably not been included in any estimation of Mumbai's size, comprise 13 per cent of the total city, occupying 61 sq km. What are known as "No Development Zones" or NDZ in government parlance, excluding hills, mangroves and wetlands, comprise 8 per cent of the city with 40 sq km. In toto, once lakes, tanks and ponds, beaches , promenades and other non-buildable areas are taken into account, the total amount of open space adds up to 201 sq km, or 41 per cent of the total. The "Open Mumbai" approach expands public space by nearly 75 per cent when compared to the existing reservations under the Development Plan.

Salt pans, which have been eyed by builders, are part of these accessible spaces, along with rivers. It turns out that Mumbai has four much-abused and neglected rivers; citizens are only familiar with the Mithi, which overflowed during the devastating flood of July 2005. Nullahs too are included, and Das' plan is to network the banks of these rivers and nullahs for pedestrian and cycling tracks. The wetlands, which are treated as wastelands, include the coast off Sewri which is visited, as it presently is, by hundreds of flamingos.

The same exercise can be conducted for other cities in the country, which will yield fascinating results. Das has used Google maps extensively, which were compared with the areas shown in the Development Plan. The exhibition has been embellished with aerial photographs, which have been taken by Dinesh Mehta, ingeniously using a kite with a camera attached to it.

While Marine Drive is the city's largest and oldest promenade, Das has pioneered the creation of two entirely new promenades in the western suburbs of Bandra and relocated the hawkers from Juhu beach. For the first time in decades, citizens see the sea when they arrive at the beach. He is also behind what is planned as the "nourishment" of the beach at Dadar, which is facing severe erosion. The attempt is to arrest the erosion of sand by employing Dutch technology and placing physical obstacles to such a process, a consequence of unplanned land reclamation in the southernmost tip of the Mumbai peninsula.

Das has also redesigned the open space in front of the iconic Gateway of India, with the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH). Previously, an incongruous barricaded Mughal garden occupied much of this space. Now that it has been opened, and the clutter of kiosks sought to be cleared, as many as 3,000 people can be seated for a concert at the site.

Four seminars were held at the National Gallery around themes like the city's natural assets and policies for public maintenance of open spaces. The last, on April 7, dwelt on citizens' participation in the Development Plan. To activists' dismay, the task of preparing this plan, which will extend from 2014 to 2034, has been entrusted to a French consultancy firm. If a Mumbai Vision plan prepared two years ago by Singapore architects, Surbana, is any indication, such exercises can be way off the mark.

A very worthwhile suggestion was made at the last seminar by Gautam Chatterjee, who is Principal Secretary for Housing in the Maharashtra government.

Instead of going in for 20-year plans, the predictions of which are more often than not belied by subsequent developments, he believed it would be

better to have five-year plans, which can be monitored more carefully and realistically. Needless to add, citizens' ought to play a much bigger role in

preparing such plans, just as the mapping of Mumbai for the first time has been done by citizens and will serve as an eye-opener to any government.