An impoverished adivasi woman, Shanti Hessa, of Barajhikapani, West Singhbhum district in Jharkhand was forced to sell her land because she incurred expenses to the tune of Rs.12,000 when she was admitted to a private clinic following complications after the birth of a still-born child. There is a government health centre in the area where she first sought treatment, but the doctor there turned her away because she did not accede to his demand of a bribe of Rs.1000.

Hessa's case is not isolated, even in this one district. In the village of Chandarjharke the Oraons, a tribal community expressed concern because a new Auxiliary Nurse and Midwife (ANM) was skipping her mandatory rounds of the village; as a result their children had not been inoculated with the BCG vaccine, and the parents were anxious. Elsewhere, in the isolated hamlets of Tonto Block the adivasis wondered why 17 bottles of saline given to the ANM had not been utilised but remained in her possession.

How could Hessa and the other villagers in this remote region access their medical entitlements? How could they become aware of their health rights? Most of them regarded doctors, nurses and other health personnel as sarkari log, and felt their complaints would be brushed aside if they spoke out. The fear was compounded because some of the villagers had experienced insensitive treatment at health centres.

Gradually however winds of change began blowing through this thickly forested belt of Jharkhand. Adivasis began voicing their grievances. At a jan sunwai - a public hearing - Hessa testified against the doctor who had denied her health rights. Doctors were pulled up and given show cause notices in instances where they had behaved unprofessionally. ANMs too realised they could no longer skip villages. In short there was a perceptible shift in attitude whereby healthcare services were made more accountable and responsive to the needs of the rural poor especially women and children.

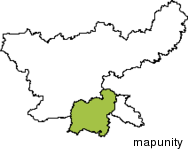

This was made possible because of an encouraging pilot project in community-based monitoring under the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) in three districts of Jharkhand - West Singhbhum, Hazaribagh and Palamu.

NHRM pilot project

The NRHM, which proposes an intensive accountability framework, has included monitoring by village-based communities as one of its key strategies. Launched in 2005 the project is a visible demonstration of a unique handshake between the community and the health system. The communities under the project are facilitated by civil society organisations (CSOs) and panchayati raj institutions. (Although Jharkhand has still not held panchayat elections a traditional system of local self-governance prevails, with the munda (chief) having the right to call for gram sabhas).

•

Claiming the right to care

•

Will PHFI be meaningful?

•

Universal care: Miles to go

While women's groups have traditionally been organised through self help groups to manage small economic needs, they still struggle with huge expenses in inappropriate medical treatment, especially during child birth. Thousands of women continue to die or suffer in silence because they do not receive the care they need or the respect they deserve in the medical system. Ekjut's focus is to ensure that their voices are amplified and empowered to hold health systems to account.

Community based monitoring has a few main objectives - to provide systematic information about community needs; to provide feedback according to locally developed yardsticks; to increase involvement and participation of the community; and to validate data collected by ANM, AWW and other functionaries.

Monitoring activites

The monitoring team consisting of three men and three women was set up in the villages and began its monitoring activities after an orientation programme. Activities of the monitoring team were wide-ranging, and focus on both service providers as well as those who came to the medical system for cure and treatment. They conducted interviews with women who had recently given birth, held group discussion with community members, and also held exit interviews with patients from PHCs. The team also interviewed a PHC medical officer, spent time observing a sub-centre's functioning with a checklist in hand. Interviews with NRHM's accredited sahiyas - activists who work largely as volunteers but are provisioned with some monetary incentives - were also carried out.

Ekjut began its programme in three blocks of West Singhbhum - Chakradharpur, Manoharpur and Tonto - with an orientation for the village health committees, anganwadi

workers, sahiyas and health workers. Two other CSOs were also involved. Thereafter it embarked on an awareness campaign through a kala jatha employing a

well-known local folk troupe. There was a far greater acceptance of the concepts by the villagers because the jatha used local idioms and culture.

Ekjut began its programme in three blocks of West Singhbhum - Chakradharpur, Manoharpur and Tonto - with an orientation for the village health committees, anganwadi

workers, sahiyas and health workers. Two other CSOs were also involved. Thereafter it embarked on an awareness campaign through a kala jatha employing a

well-known local folk troupe. There was a far greater acceptance of the concepts by the villagers because the jatha used local idioms and culture.

Other activities included a workshop in Chaibasa that sought active media involvement and several village meetings. This was followed up by three jan sunwais, one of them being held in the premises of the Chakradharpur hospital which was attended by the Chief Medical Officer (who is also the Civil Surgeon).

A committee for planning and monitoring of sub-centres and PHCs was also set up. The committee along with the service provider - i.e. the ANMs - then collected data and presented it to the CBM teams. The data covered subjects like maternal health guarantees, the functioning of the Janani Surakhsha Yojana, (a maternity benefit scheme launched under NRHM to reduce over all maternal mortality ratio and infant mortality rate by increasing institutional deliveries) adverse outcomes and denial of services, disease surveillance, child health, quality of services, quality of services in vulnerable groups, response of the community to sahiyas and so on.

These reports and the report cards of the sub-centres and PHCs that grade infrastructure and HR, availability of medicines or instruments, quality of services and care and implementation of various schemes like JSY were ingenuously presented through novel use of colours. Red signified alarm, yellow stood for fair and green for good results.

Villagers of Chandharjharke and health activists at a meeting

to discuss how to raise health awareness.

Impressive results

The pilot phase of intervention by community-based monitoring yielded some impressive results. It showed how with heightened awareness demands for ante-natal care and for the monetary incentives given under the JSY (maternity benefit scheme) had increased. Anjuli, a sahiya, explained, "If the nurses or ANMs in hospital refuse to give the women their financial entitlement I just ring up the top officials or even the Civil Surgeon."

One of the cheering aspects has been the Civil Surgeon's active and dedicated participation from its very inception and the proactive approach of the District Programme Manager and the District Nodal Officer. The behaviour of the service providers has also undergone a metamorphosis. Mohan, a Ho who is a coordinator for Ekjut, said that there was noticeable difference in the attitude of district officers who became much more active in touring districts and in conducting camps.

This brought about faith in the government systems. The media too extended its support giving far more coverage to health issues and highlighting problems as well as positive outcomes.

The laudable performances of the CBMs were largely because the programme is owned by the community and the village health communities. Again since the community itself

monitored the services meant for its benefit, there was far greater involvement and an increased knowledge of health rights. Today, although the pilot phase has ended, the

gains from the trials remain. The village health committees are now sufficiently empowered to continue the good work.