The first few months of a new government are the ones with the most potential. Newly elected or re-elected leaders have the wind of public support beneath their wings, and therefore they have the political capital to implement new ideas and initiatives. Mamata Banerjee has just won her third term in West Bengal, and Pinarayi Vijayan his second in Kerala. M K Stalin has taken charge of Tamil Nadu for the first time. Assam too has a new leader, and a new CM has taken over just a week ago in Karnataka, and but these two must work within the lanes set by their national leaders, unlike the others.

The development goals are roughly the same, no matter which party one is from - to help make their respective states better places to live, work, and invest in. Beyond that, however, the first steps taken by an administration also signal their stance on important political questions. In India, one of the most important of those questions pertains to Centre-State relations. How does a State government see its relationship to the powers-that-be in New Delhi?

Different, and yet the same

A hint of its answer has already come from TN, in the form of a distinction being made by using the constitutionally-defined 'Union', rather than the commonly-used 'Centre'. These steps are probably the first stirrings of a new stance, one that favours a more federal India. This isn't surprising: a federal country gives all its state governments lots of powers and space to innovate and to experiment and to implement what works best for the citizens of their state. And leaders of regional parties can naturally look to federalism to advance their states' interests, and their own personal ambitions too. Leaders of national parties also learn from the initiatives taken in each state to apply them elsewhere.

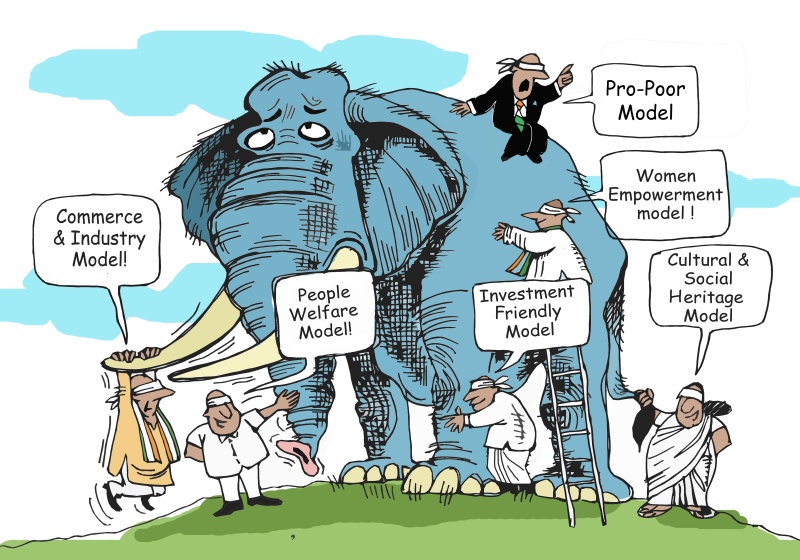

It is odd, therefore, that most Indian states do not use these freedoms to create their own development model. For instance, the two TMC governments of the last ten years have mostly done what other governments have. Some things were new to Bengal -- schemes and support for women, and for some sub-groups of voters. Some things were done better than in other states -- municipal governance and urban transformation, or defending Bengal's unique cultural and social heritage. Some things were the same -- investment summits that bring limited benefit; modest improvements in electricity a bit better transport network; IT and service sector growth; and suchlike.

Kerala and Tamil Nadu have their own models -- Kerala's is driven by welfare of the people through decentralisation, and Tamil Nadu by efficient government services and attracting private investment. Kerala's government has responded well to crises, but there are lingering questions about the trajectory of its economic development.

Illustration by Farzana Cooper.

Broadly, however, these directions too do not clearly leverage a federal view of India. Instead, they are at best administrative improvements and innovations within a uniform political landscape. As the voter might say, they are all the same. In this respect, at least. And that may be all we can expect, for now. While we will continue to see demands for more powers to states, and clever positioning by politicians to take advantage of 'local' sentiment, it is unlikely that these will grow into full-fledged endorsements of federalism itself by political parties. That is a much larger step, and as yet there is no sign that any party is ready for that.

Nonetheless, a better version is possible

But even in this limited way, more could be done, and needs to be done. The coming decade will bring new challenges. Climate change, competition, social media, identity politics, informed citizenry that expects more, apart from managing the existing challenges of healthcare, education, and rapid urbanisation - this last one is something that the CMs of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and West Bengal are already grappling with. So are those of Karnataka and Assam. Underlying all these are important governance challenges, which are needed to improve citizens' quality of life today and tomorrow.

The wishlist for governance and institutional reforms is long, well-researched, and even more necessary in 2021 than ever before. It can be done by any ruling party in any state. These three CMs though come from regional parties (including the LDF in Kerala) who have the most freedom to chart their own path, and the most need to demonstrate a superior model of governance and development to set themselves apart from their political opponents. In the next few months, while they still have political and electoral support, the new CMs can focus on these more difficult issues, apart from everything else they are already doing, especially in managing the pandemic.

One important area that these states can take the lead on is climate change, given their high vulnerability to rapidly-changing environments. |

Start with their own legislatures. These should be stronger. Already, the lawmaking power of MLAs has been severely curbed by a badly designed anti-defection law. On top of that, MLAs' involvement in administration is also weak. They should do more than just ask for transfers, promotions, and supervise the implementation of schemes. State governments could easily allocate funds for a support cadre for MLAs to help them research and understand problems in their constituencies. They could increase the duration of Assembly sessions. They could make the Standing Committees stronger. These are all stroke-of-the-pen decisions, and they will swiftly set precedents that other states cannot ignore.

The judiciary, especially the lower judiciary, of all states is crumbling with poor infrastructure, and even poorer processes of working. The CM and the Chief Justice of the High Court can together create a committee that suggests urgent and medium-term improvements of all the courts in the state; improves the procedure of working; trains judges; and ensures that the backlog of vacancies of judges is bought to zero in the next year. This will improve the courts, and since almost every citizen has to reach out to the court for something at some point in their life, this will also be a visible sign of progress.

Strengthening the public prosecution system in the state by hiring more prosecutors, training them better, giving them more resources, and rewarding them for their successes will hardly cost anything, but it will improve the 'law' side of 'law and order' and increase voters’ confidence in timely justice. Improving preventive and investigative policing will also not be difficult; there are many directions from the Supreme Court to support this. An impartial and effective police force may harm the interests of some local political functionaries of the ruling parties, but it will win the trust of the voters.

Another area that these states can take the lead on is responding to climate change, given their high vulnerability to rapidly-changing environments. West Bengal should have the highest ratio of renewable energy; the most investment in drinking water; and the most sustainable methods of garbage collection. Tamil Nadu should grow the most number of trees of any states. Kerala can lead in sustainable agriculture. Karnataka can surely develop some tech-enabled forecasting solution! None of this is difficult.

Tamil Nadu's Economic Advisory Council has been well-received. Kerala and West Bengal should have this too, and perhaps complement it by creating a Partnership Commission that advises and helps implement development initiatives by improving the capacity of the state, market and society to work together.

Institutions, not initiatives

What is common to all of the above ideas? They are institutional. They would mostly rejig the institutions that already exist to do much better than they have so far, and occasionally create new ones to fill gaps. This can be done without too much new expenditure, and therefore be all the more attractive to governments.

|

But such an institutional focus would also require commitments to a new imagination of governance itself. It requires the internal procedures of governments to be modified to make it easier to partner and to share risks. It requires common templates for cooperation; for judging success and failures; and for learning from best practices from other Indian states, or elsewhere in the world. Quite often, this is the reason that governments don't choose this; as much as they would like the benefits of such reforms, they are yet to come to terms with the implications these steps would have for power-sharing and accountability.

Every state frequently announces initiatives and schemes. Some succeed. Some languish to be replaced by new schemes. The work of strengthening existing institutions of governance; creating more friendlier processes of administration and justice; and improving cooperation within and across government agencies and with civil society and businesses is a long slog. Starting these reforms at the start of their tenures allows Chief Ministers a few years to help make them happen. For the newly elected Chief Ministers, the clock is running to implement as many institutional reforms as they can.