Even in the best of circumstances, city news readers and viewers don't see migrants and other marginal communities as equals, as fellow citizens. The ongoing pandemic has put the migrants' plight front and center, and that has unleashed an enormous amount of compassion. But given the background, this generosity will run out of steam in all likelihood in a few months. The gift of a newly attentive India isn't really something that disadvantaged people can count on very much.

What's the alternative? One way of thinking about this differently is to swap the positions of the onlookers and those being looked at. Could we reverse the gaze between the powerless and the powerful? A second difference is to think of what migrants - and other poor people - may be able to demand as rights, rather than obtain as charity. The advantage of this is that what they can insist on as citizens has no expiry date, unlike fleeting empathy.

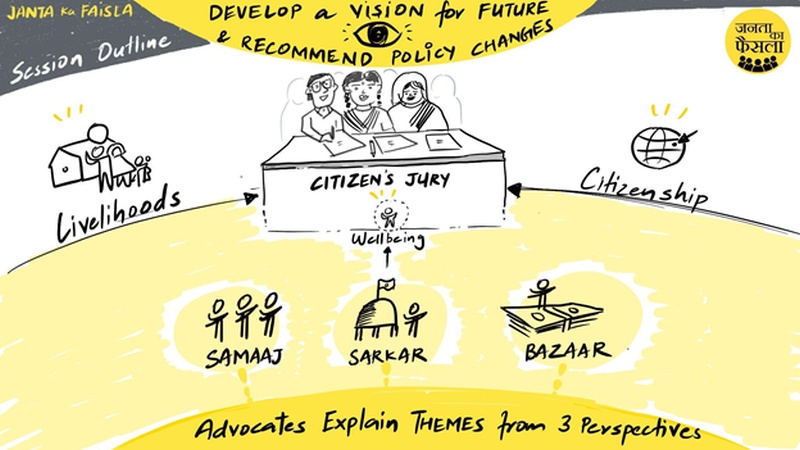

Instead, what we need is to create distributed and durable institutions that collect the wisdom of the citizens and deploy that collective wisdom to address the wicked problems that beset Indian society. Socratus seeks to be the midwife of that collective wisdom. We created Janta Ka Faisla as a platform for deliberative democracy to explore this. JKF seeks to address the needs of migrant workers and represents them as full citizens of India. The complex challenges of Indian society can only be solved by citizens themselves; it's only through distributed democratic institutions framed around citizens' needs that we can effect changes in society, governance and the economy, and create a flourishing future for all of us. Janta ka Faisla is one such institution, which takes the form of a jury.

The first JKF consisted of a jury of migrant workers drawn from different occupations and regions from Chhattisgarh. The jury addressed the challenges of Indian society. After hearing presentations from experts and weighing the presented options, the jury passed judgment on the choices available to them and made that judgment available to the public.

Illustration by Srinivas Mangipuddi.

The first Janta ka Faisla was organised by Socratus in partnership with the National Foundation of India and Chaupal in Raipur between 11 and 14 July. The heart of the JKF is the jury itself, and the life experiences and wisdom they bring to the verdict. A jury of migrants from Chhattisgarh was selected through an intensive process, starting with an initial list of 1.5 lakh migrants collated from various NGO and volunteer databases, followed by an automated round of calls with about 15,000 migrants, at the end of which several rounds of interviews led to a 15-member panel of jurors.

This jury heard from a range of experts on topics such as employment conditions at destinations, i.e., wage rates, timely payments, workers' health and safety, and alternatively, local livelihoods in agriculture and non-agricultural industries, livelihoods based on the commons, including forests and inland fisheries; migrants' entitlements to food security and health and how government schemes such as the PDS can deliver those entitlements in both source and destination states. However, the JKF platform is not intended for a discussion on policies for migrants alone as that would frame them as a special interest group asking for support from the state.

Themes covering various aspects of migrant workers' lives were deliberated over four days. Each theme had 'advocates' or 'expert witnesses' representing Sarkaar, Bazaar and Samaaj. Experts include government and industry representatives, civil society actors, lawyers, academics, journalists etc. Advocates deposed in front of the jury, and argued their case; these were in different forms and formats - a perspective, an analysis or a school of thinking, or a practical solution, a defence of interventions already underway, recommendations for improving some existing law or scheme etc.

The advocates' or expert witnesses' pleadings were heard on the below-mentioned themes. For each theme, 2-3 expert witnesses presented their perspectives to the jury members for about 15-20 minutes each (including clarifications). This was followed by jury deliberations, in private, facilitated by the amicus curiae in the presence of members from the oversight panel. The last day was reserved for the compilation of the jury's views culminating in their final verdict.

Illustration by Srinivas Mangipuddi.

While a detailed report on the just concluded event is in the works, I am sharing a few reflections while the event is still fresh. The first and most important reflection is that the jury took to their task with great energy and seriousness of purpose. They asked penetrating questions of the experts - treating them as peers rather than superiors - and didn't hesitate to challenge them when they felt so.

Second, the format of the event leads to a form of 'positional objectivity' on part of the jurors and other participants. By that, I mean that the jurors were not acting as partisans for their special interest but as fair representatives of their community, and at least in principle, as representatives of all Indians. We need to distribute this capacity to take on this positionally objective role as widely as possible.

|

|

Finally, the judgment has detailed recommendations for policy makers and provides an effective way for those in decision making positions to enter the world of their constituents. User-centred design is all the rage when creating apps and other modern technologies - why not bring those design principles to the public sphere?

In short, the JKF was deliberative democracy at work; creating a society of the people, for the people and by the people. We hoped and expected that the deliberations and the verdict of the first Janta ka Faisla will become a model for how Indian society should learn from its most vulnerable citizens, both helping them live a life of dignity and in creating a better world for all of us.