Like surangas, the man-made tunnels for water, this 79-year-old Karnataka farmer, who has half centuries attachment for surangas is lesser known outside. It was Manimoole Achyutha Bhat, an arecanut farmer's family that brought this traditional water harvesting system to this village Manila in Dakshina Kannada district. Thanks to this system, today including Bhat, many neighbouring farmers have no water shortage.

Achyutha Bhat's family had nearly 20 surangas dug in their property. Fourteen out of this are still serving them. Surangas provide them water not only for irrigation, but for drinking and domestic purposes too. What's more, they don't have to spend a single paisa for diesel or electricity to get this water. All the water is free flowing - in the sense they flow due to gravitational pull.

In the 15-acre barren hill slope the family got decades ago, five acres containing arecanut and coconut gardens stands today, courtesy these surangas. No other water body like open well is feasible here because of the slope and soil type. "If and when we foresee some water scarcity," explains son Govinda Bhat, 51, "we go for one more suranga."

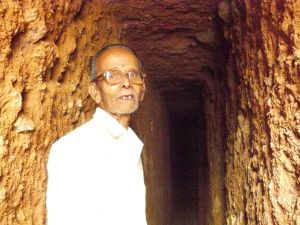

![]() Achyutha Bhat has a passion for surangas that began at childhood.

Pic: Shree Padre.

Achyutha Bhat has a passion for surangas that began at childhood.

Pic: Shree Padre.

"They dig one suranga each year", is how the villagers talk about Manimoole. Though this is exaggeration, points out a smiling Achyutha Bhat, "After my marriage at 21, four consecutive years might not have passed without us getting a suranga dug."

Manimoole is an area of the village, and there are about 20 houses here belonging to farmers and farm labourers. All have surangas that yield good water. For most of these, Achyutha Bhat might have divined water.

As the land is sloping, cultivating is possible only by leveling plots at different heights. What Bhat's do is a much planned, decentralised system of irrigation. Before leveling a plot, they dig out a suranga at least 25 feet above that. Once they strike water, the plot levelling goes on. The water oozing out of the suranga is collected in an earthen tank and irrigation done by mist jets. Thus they ensure pump less irrigation to all their plots. They have six water tanks today. A few out of these are inter-connected too.

Their old house was at a lower level to which a suranga was catering water earlier. After they constructed the present new house, the force from old suranga was not enough to supply water to the house. As such, they went higher up and dug a suranga there. Today, starting from kitchen, to all the water taps in and out the houses, this suranga at the highest elevation supplies ever fresh water.

"Fortunately, we are blessed with water within 50 kolu (one kolu means 2.5 feet) if we dig suranga after careful divining," Govinda Bhat says proudly. His calculation is simple. "For a 50 kolu suranga, we need Rs.15,000 as per present wage rate. But once we spend that, there is no worry thereafter. No recurring expenditure. Needn't bring diesel nor we have to bear with the long power cuts."

Achyutha Bhat was fascinated by this water harvesting structure since his childhood. It was in the nearby village Padre where he was learning Sanskrit he first saw a suranga. His father who was frequenting the Sanskrit pathshala too was so impressed that they wanted to go for one. So, when Achyutha Bhat's was aged 10, the Malayalee moplahs from Kerala were brought to dig the first suranga of the village. By seeing the process of digging, this family learnt its intricacies. Thereafter there was no looking back.

Obsessed with surangas

Achyutha Bhat was attracted to surangas for many reasons. First, it would provide ever flowing water. Second, since the water flows out of gravity no other energy or fuel is required. Step by step, he mastered all the departments of suranga digging like water divining, going on digging with a small gradient, bringing the dug lose soil out, sensing danger while digging, changing the direction of the suranga, if needed to obtain water or more water etc.

According to an estimate, today Manila village would be having more than 300 surangas. It has a total of 480 houses. Says Govinda Bhat, "At least half of the houses have at least one suranga for their drinking water purpose."

"Digging surangas is not such a skill that can't be learnt by anybody. With hard working nature and has the necessary common sense, anybody can for that matter," reassures Achyutha Bhat. Interestingly he doesn't entrust the suranga digging to professionals. Each time he wants to, he gets it done by their regular ordinary workers by giving them incentives. This way, in the last half century, at least two dozens of farm labourers have learnt the art of digging surangas here.

Manimoole can be very well described as a 'gurukula for surangas.' "Of course, those who learn the skill from here have been called to dig more and more surangas from the nearby farmers," says Govinda Bhat.

Bio-indicators

Added to that, Achyutha Bhat has gained the capacity to identify the points for digging surangas. How does he do that? "Generally, I look out for water indicator trees such as dhoopada mara (Vateria indica) , basari mara (Ficus virens), etc. Even the fast growing uppalige mara (Macranga indica) is an indicator. Termite hills on a row is another indication," he says.

Starting from sixties - since then the digging of surangas increased in Manila - though he hasn't kept count, he must have located points for at least 100 surangas. Recalls he, "A few out of this like Aithu Naika who were planning to sell property thinking that there is no water have got water."

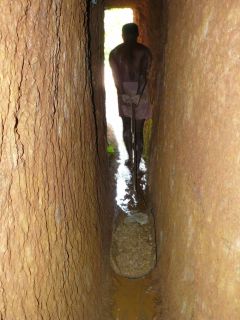

![]() Transporting dug-out soil in a hand pulled trolley

.

Pic: Shree Padre.

Transporting dug-out soil in a hand pulled trolley

.

Pic: Shree Padre.

At 79, Achyutha Bhat is still very active. Laughs Govinda Bhat, "he has this habit of entering the suranga after the labourers have left and digging for half an hour. His enthusiasm to look out for water can't be dampened. Even if we start a new suranga tomorrow, I'm sure; he will physically join hands with workers once a while."

Adds he: "In these days of expensive and scarce labour, for a coconut from our lowermost plot to come up to the house, we have to spend 50 paise. It is easy to be fed up by this and to sell this property to search our luck in other locations. But where can we get adequate amount of free flowing water till summer end?"

Dying skill

Of late, digging of surangas is on decline in hand counts of villages where this was in practice earlier. Reasons are many. First is the introduction of bore well machines that dig a well in a single day. Numbers of skilled workers who can dig surangas are decreasing. They get better remuneration in other works like in new rubber plantations. There is risk in suranga digging. Though rare, injury or death by collapsing of surangas while digging has happened in past. Yet in Manila and neighbouring Bayaru village of Kerala, it has not completely reached to grinding halt. Once in a while a suranga is dug here and there.

Govinda Bhat is optimistic. He doesn't think that the skill of digging surangas would die in near future. "So far as those interested in getting surangas dug are there, it won't die. It won't die for the want of diggers," he confides.

Interestingly, half of the houses in the village have a hill on the back or front. This is a pretty ideal situation for surangas. Achyutha Bhat feels that there is still scope to dig more surangas in the village. "If the banks start giving loans for this purpose, there would be more takers. Why can't they finance this traditional, proven sustainable system than financing bore wells that aren't dependable?" he asks. In Manila, though there are about 200 bore wells, according to Govinda Bhat, only about a dozen are yielding water.

Achyutha Bhat who brought surangas to Manila has not only been instrumental in extending it to the whole village, he has also kept the tradition alive for decades by training many newcomers.