A key target of the Global Biodiversity Framework, whose first draft was published recently, is to conserve at least 30 per cent of global land and sea areas as Protected Areas (PAs). The framework is intended to advance the goals of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity. But PAs, though crucial, are not enough to conserve biodiversity, especially in the case of landscapes where they are not well connected, and buffer areas are largely multi-use.

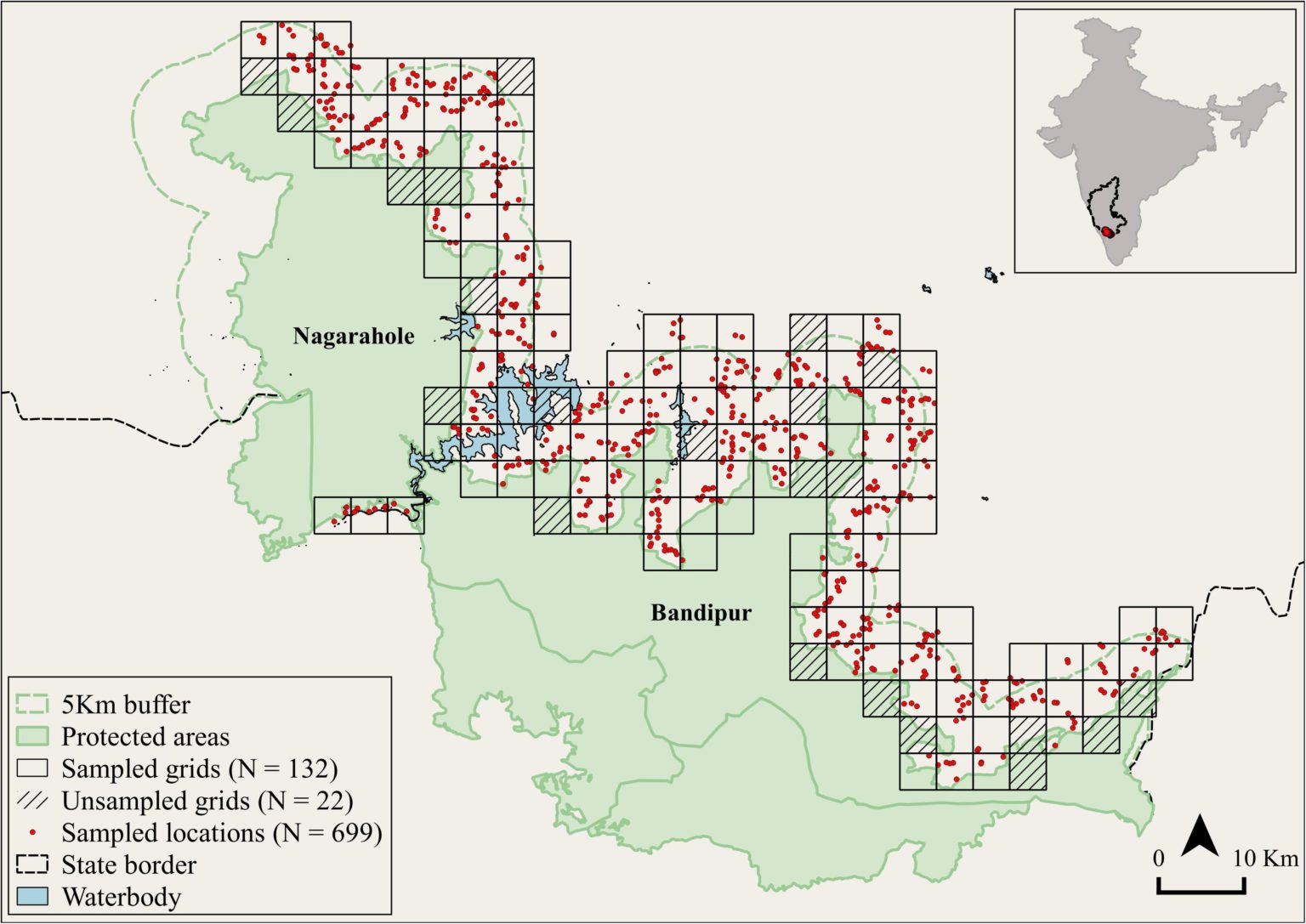

One way to enable wildlife conservation in such areas may be to monetarily incentivise landowners. A new research study examined this by surveying 699 landowners in villages around Nagarahole and Bandipur National Parks in Karnataka between April and July 2019. The researchers report that 81 per cent of the surveyed landowners said they would be interested in adopting wildlife-friendly land-use programmes under an incentive programme that would entail setting aside a portion of their land for growing native, fruiting, and medicinal trees, while the rest of the land continued to be managed as it is managed today.

Their interest in adopting this, however, was dependent on a monetary incentive of Rs. 64,000 per acre per year. This could be utilised to cover upkeep costs like labour, or even for the procurement of saplings of medicinal trees. These findings suggest that wildlife-friendly land use in shrinking wildlife habitats and expanding infrastructural developments could supplement rural incomes and potentially expand habitat for wildlife, thereby being a promising conservation strategy. The researchers also opine that growing wildlife friendly trees along with agricultural crops will reduce crop loss from elephants and wild pigs in the area, and create wildlife tourism assets as sources of revenue for landowners in the future.

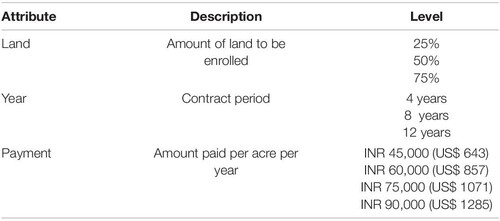

Attributes and levels used in the choice experiment. Table from study.

Human-wildlife conflict and larger conservation goals

Dincy Mariyam, lead author of the paper and research assistant at the Centre for Wildlife Studies (CWS) said that the authors were familiar with the challenge of conflicts in the region, because of the organisation's ongoing work with Wild Seve, a programme run by CWS to provide effective access to government-run compensation schemes aimed at tackling human-wildlife conflict. "There are a lot of agricultural losses from conflicts with elephants and wild pigs in these areas. And this was my starting point for the research," she explained.

The study found that a majority (84 per cent) of the villagers surveyed in a 5-km buffer zone around the two National Parks (see map below) reported facing losses due to wildlife, and crop damage was the major (83 per cent) form of loss. Erratic weather was another reason for agricultural losses, Mariyam added. Post an initial contract period, when the compensatory incentives stop, tourism could be an incentive for the farmers and landowners, as the wildlife-friendly trees create a wildlife tourism asset in the area, said Mariyam.

"If you look at conservation the world over, you will see that there are multiple ways in which areas are protected [for conservation]," said Krithi Karanth, co-author of the paper. "Models include government-owned lands where wildlife conservation is a priority like national parks and sanctuaries, privately-owned wildlife parks and community-managed wildlife habitats. For example, there are community-based wildlife conservation initiatives in countries like Namibia and privately-owned ranch lands in Brazil that focus on jaguar conservation," she added.

In India, around five per cent of the land area has been set aside as PAs under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972. "But there is a lot of wildlife outside the PAs, on communal and private lands. We need to find solutions that allow humans and wildlife to coexist outside the government-mandated protected areas,” Karanth explained. “The larger goal is to create different models of conservation and land-use that facilitate more space for wildlife," she added.

Criticism of the model

One critique of the model is about whether it might lead to more conflict. "Given that conflict resolution is one of the aims, would it not work at cross-purposes if large, potentially dangerous wildlife and people, are brought into closer contact [because of wildlife-friendly land-use]?," asked conservation scientist, M D Madhusudan. He added that the study, while stating the benefits of the choice experiment, does not seem to represent potential costs that are also implicit in the choices, such as those of human-wildlife conflict.

There is also criticism of the sampling methods and choice-based assessments. The survey was conducted in 287 villages located within a five-kilometre radius of the Bandipur and Nagarahole national parks. Most landowners were willing to adopt wildlife-friendly land-use practices. But some were not; those who opted out of the programmes cited intent to continue ongoing agricultural practices; inadequate economic benefit; paucity of land to commit to the program; lack of faith in institutions, and water scarcity.

|

|

Photo: Elephants crossing a road in Bandipur National Park, L. Shyamal/Wikimedia Commons.

Some experts, not associated with the study, critique the method of the survey. "The paper does not contain enough information to understand whether the sample was truly representative [of the population]," said Divya Karnad, Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies, Ashoka University. She highlighted the need to include the total population size and how much of it was sampled, and the number of villages around the parks, as part of the methodology. Karnad also didn't favour choice-based assessments in general. "It gives a good idea about what people think they are willing to do under experimental conditions. But it may not translate into what they will really do given multiple pressures like indebtedness and role in society," she explained.

Madhusudan added, "The approach adopted in the paper might be valuable as a descriptive tool that might help identify and explain factors that underlie actual choices made by landowners in switching voluntarily from agriculture to growing native trees in real-world circumstances. But it is less useful as a predictive tool because it is based on how people navigate hypothetical choices under highly simplified scenarios."