Over 90 per cent of planted cotton seed in India is genetically modified Bt cotton owned by the agribusiness giant Monsanto. The multinational has cast its corporate spell over cotton seed markets in the country, and has been pushing for the introduction of genetically-modified food crops as well. This ironic new avatar of Monsanto as a promoter of "sustainable agriculture", however, buries a murky past involving chemical toxic products.

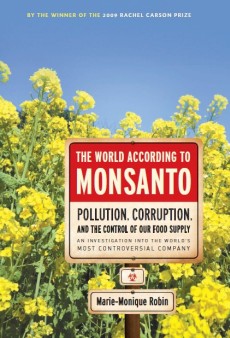

Marie-Monique Robin's thorough investigation into the controversial company, presented in her book The World According to Monsanto: Pollution, Politics and Power, exposes the history of this corporation, which positions itself as an agricultural company, rather than one that produces chemicals.

Combining extensive research on the Internet, discoveries from her travels, and interviews with affected communities, farmers, activists, whistle-blowers and researchers, Robin presents a riveting history of the corporation, and the trail of devastation in the wake of its campaigns. The North American multinational, which is now the world's largest seed company has spread its tentacles across the globe. The author tells the complex and troubling story of how the corporate impulse of one company has left a toxic footprint with tragic consequences.

Robin takes us back to Monsanto's origins, revisiting a history of death and disease linked to PCBs, or polychlorinated biphenyls, chemical compounds "that embody the great industrial adventure of the late nineteenth century". These chemicals produced by Monsanto for four decades until they were banned in 1977, were used as coolants in electric transformers and industrial hydraulic machines, and also as lubricants in plastics, paint, ink, and paper.

Emitted in large quantities in the atmosphere of Anniston, Alabama in the USA where one of Monsanto's factories was located, and thereafter dumped in its streams and deposited as contaminated waste in the heart of the city's black locality, the PCBs wrecked people's health causing cancer, repeated miscarriages, and learning disabilities and neurological defects among children. Wading through a "mountain of documents" comprised of Monsanto's memoranda, letters and reports, the author reveals how the corporation turned a blind eye to the severe health impact suffered by factory workers and affected communities.

Robin narrates the chilling story of Monsanto's work with Pentagon strategists to develop the use of the herbicide 2,4,5-T as a chemical weapon in the Vietnam war.

Another card from Monsanto's deck was the herbicide Roundup, which was aggressively advertised as a biodegradable and harmless herbicide in the year 2000. Monsanto's patent on Roundup was about to expire later that year. The stakes for the multinational were very high, because it had grand plans to flood the world's fields with 'Roundup-ready' crops manipulated genetically to withstand spraying with Roundup. With a knack for explaining technical detail in layman's terms, the author untangles the Roundup story. Monsanto's business-as-usual approach, she writes, risked people's lives, their health, and ecological well-being.

Robin's investigation into the experience with the artificial bovine growth hormone manufactured by Monsanto reveals its questionable tactics to foist the hormone onto the dairy market in the USA. In the process, the company appeared willing to go to any lengths to ensure that consumers were kept in the dark. The recombinant bovine growth hormone, or rBGH, is a transgenic hormone that boosts milk production in cows, but causes debilitating diseases including mastitis - an inflammation of the udders - in cows injected with it. This, in turn, leads to milk yield containing pus and antibiotics used to treat the inflammation. Monsanto's tactics to reap profits from this product makes for compulsive, or rather, repulsive reading.

The author interviews cancer specialist Samuel Epstein, who explains the linkage between rBGH and increased risks for cancer. Keeping the readers' attention hooked while plodding through thick reportage, the author narrates how whistle-blowers were fired when they raised their voice against Monsanto's foul play, how the Food and Drug Administration of the USA worked hand-in-glove with the company to protect it, how scientific research was manipulated, how the press was controlled, and crucially, how the 'revolving door' delivered former Monsanto employees at the doorstep of American government institutions, where they did the company's bidding, and vice versa. Astonishingly enough, dairies which labelled their milk as free from artificial growth hormones were sued by Monsanto.

Travelling to Mexico, Argentina, Paraguay, Brazil and India, Robin throws light on the story of Monsanto's pervasive control over agriculture through its genetically modified seeds. She visits the state of Oaxaca, one of the poorest in Mexico, to track the contamination of corn by Roundup Ready and Bt genes, though the country had declared a moratorium on transgenic corn crops in 1998.

The spread of Roundup Ready soybeans at an average speed of more than two million acres a year in Argentina resulted in substitution of food crops with GMO monocultures, a concentration of land-holdings, and an expansion of agribusiness at the cost of family farming. The "breadbasket of the world" was thus transformed into "a producer of cattle feed for the European market". The author describes the damage caused by the invasion of Roundup Ready soybeans thus: rising agricultural costs, pest resistance to Monsanto's pesticides calling for increased use, a public health crisis, pollution of the air, soil and water table, an extremely high rate of deforestation, and a livelihood crisis for small farmers who became labourers.

In a chapter titled India: The Seeds of Suicide, Robin reports from her travels to the cotton belts of Vidarbha and Andhra Pradesh, where small farmers tell her about their experiences with Monsanto's Bt cotton. As Tarak Kate, an agronomist working on organic farming in the Yavatmal district of Vidarbha, explains to the author, "... GMOs are not at all adapted to our soil, which is saturated with water as soon as the monsoon comes. In addition, the seeds make the peasants completely dependent on market forces."

The author describes "an incredible scene" in the cotton market of Pandharkawada in Vidarbha, where Kate asks the farmers about their debts. "... dozens of peasants spontaneously declared, one after another", narrates the author, "the amount of their debts: 50,000 rupees, 20,000 rupees, 15,000 rupees, 32,000 rupees, 36,000 rupees." Such debt has significantly contributed to the mind-numbing tragedy of farmers' suicides that have convulsed the countryside, and that are in no small part due to the Bt fever which has taken over Indian cotton farming.

The book lays bare extremely dense subject matter with several interconnected threads in lucid layman's language without compromising on technical detail and a thorough treatment. That the author chose to include an entire chapter on the invention of GMOs is a case in point. However, while presenting a compelling case against Monsanto, the book on occasion resorts to alarmist metaphors and language, which can prevent an engagement with readers who might not agree with the author's point of view. While Monsanto's history is indeed alarming, the author's arguments would perhaps have been enhanced and made more effective by more measured language in certain instances.

Robin's book achieves the difficult task of interweaving in-depth research with investigative journalism to present solid arguments against Monsanto's chemical and genetic manipulation of our food system, and our world itself. The book is of great relevance to readers in India given the serious inroads the company has made into our seed markets, with severe consequences for farmers. Indeed, the company behind the Bt mania has a lot to answer for.