When Bhaskar Prasad packed his bags from New Delhi to go to Patna in Bihar three years ago to set up systems for the state government that would bring in e-governance, there were not many smiles around. He also was a bit skeptical, but he knew that if he could do it in what is seen as a difficult state where vested interests would jeopardize the idea, it would be a watermark in his life. He went.

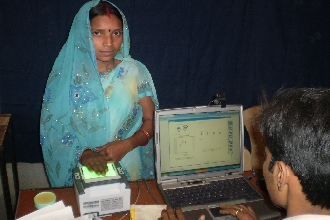

![]() Fingerprint detection helps avoid scams in payment to labourers. Pic: IL&FS.

Fingerprint detection helps avoid scams in payment to labourers. Pic: IL&FS.

One of the many ambitious projects he undertook was to create a surveillance system in all the 53 prisons in Bihar. Seven hundred Internet Protocol based cameras were installed to keep watch. It was not easy. There were lots of security restrictions that kept his workers out of the jail for around 16 hours a day. Prisoners did not like the idea. Obviously. Many of Prasads men felt so intimidated by the prisoners that they quit. Two of them had marriage plans but it broke when their would be in-laws discovered that they were working in a jail. Today, jail officials can log on to the computer and watch live videos of their prisoners activity from their offices or homes. Or even when they are traveling outside their state.

Prasad is Head, e-Governance, Infrastructure Leasing and Financial Services (ILFS) which got into a joint venture with Bihar e-Governance Services and Technology Limited. This was done in September 2006 to create a system for delivering e-Governance.

Technology to the rescue

Another project in Bihar that was beneficial was an attendance system for the National Rural Employment Guarantee Schemes with smart cards. It showed immediate results. Earlier there were numerous problems like fake musters, job cards not being issued, labourers not being paid on time and not paid according to the work completed. The labourers now use an automatic finger identification system to record their attendance. A web camera takes their pictures and their application forms are electronically captured. The wage goes directly into their bank accounts. It is liberating thousands of labourers who were getting a raw deal.

Several villages in Bihar have a bank official visiting them with a handheld device to help them with their bank transactions by swiping their smart cards. Earlier, villagers had to travel to the nearest town to transact bank transactions. Now the official helps them with a biometric hand held device which reads the finger print of the client and approves the transaction. So, they do not have to visit the bank or even an ATM. It also has an integrated voice system in dialects like Bhojpuri, Mythili and Hindi so that even if they cannot decipher the readings on the hand held terminal they can hear how much money has been withdrawn. The voice system can be changed to any dialect or language depending on the area it is being used.

This system is also in use, in fact even better, in Haryana and Gujarat. In Bihar, bank officials are slightly wary of giving cash to an official who has to move around because of insurgency and crime.

The card called e-Shakti is now operation in Baditangrela village in Nawbhapur block of Patna district. 900 e-Shakti cards have been used here, says Prasad. After Patna, it will be rolled to all the 37 districts in the next three years covering 2.5 crore beneficiaries in Bihar. Its cost: Around Rs.300 crores. It is a transparent system and there is no room for corruption. There is a 40 to 50 per cent leakage of funds today. This will stop. It will be a paradigm shift, says Prasad.

In future, it will be used as a multi services card as more applications can be added to it like a ration card, pension card, social security, health services, land records, birth certificates and so on. There is no limit to imagination. We just need people to implement it. There is no multi-card system anywhere in the world right now. But we can do it, says Prasad gleefully.

The benefits of Information Technology are slowly becoming obvious to rural India as villagers use their telecentres to dig the truth. Villagers in Uttar Pradesh recently asked for print outs of those in their village who get state funded pension. The e-kiosks known as Lokvani in Uttar Pradesh provided the names of these beneficiaries paying a small fee.

Under the old age pension scheme, the UP state government pays Rs.300 per month to those who are above 65 years of age and below poverty line. About Rs.700 crores is earmarked for the scheme annually. In all, there are 30 lakh beneficiaries across the state. Villagers discovered to their horror that it was being siphoned off by many who were not old enough and by many who were not even living in their village.

Preliminary inquiries have shown that there are 92,000 beneficiaries who either do not exist or are undeserving. Officials of the Social Welfare Department alongwith village pradhans and bank officials who disburse the money have been found to be involved. An embarrassed state government has now ordered a physical verification of the lists in all villages.

Change comes, finally

For a long time, governance has been conducted in a conventional way that has its roots in the old British system. This defied transparency and most of the times even efficiency. For example, the Patwari used to be a powerful man till GIS-based land records copies began to be distributed to citizens through the Common Services Centres. However, change is not easy to come by and people with vested interests tend to play spoilsport.

But, digitisation of information has made it much easier and faster for them to operate. In Jharkhand, one of the backward states in the country, massive digitisation of land records is being done on a war footing.

Ambitious nationwide plan

The ambitious National e-Governance Plan (NeGP) that started in 2006 September is slowly making a quiet impact in various corners of India. The NeGP takes a holistic view of e-Governance initiatives across the country, integrating them into a collective vision of having a countrywide network reaching to the remotest of villages. It is digitising records to enable easy and reliable access to all those who want information.

Modern digital mode of governance, for example, does away with signatures, rubber stamps, cyclostyled copies of Government Orders, which all in the eyes of the common man were the signs of true governance. In the modern system, Birth Certificate copy is just printed on a normal printer at the telecentre, which is an unbelievable change for many who knew how much it took to get one delivered.

THE NATIONAL SCENE

The National e-Governance Plan aims to setup more than 1,00,000 centres will be set up in 6,23,000 villages by June 2010. The logic is that there should be atleast one Common Service Centre for a cluster of six villages so that there are adequate footfalls to ensure the economic sustainability of such centres. It can be scaled up if needed. 36,500 centres had become operational by March 2009.

Each state has given a different name to it for branding. Ultimately, the National Data Bank or State Data Centres will have ditigitised data on individuals. A statewide area network will ensure connectivity through fibre optic connections guaranteed upto the block levels.

Genesis of the Common Service Centre

The Common Service Centre has been designed on a Public Private Partnership model. The focus is on rural entrepreneurship and market mechanism to create ownership. It will also ensure more involvement of local folks who will connect to the project with more commitment and interest.

The objective of the NeGP was to develop a platform to enable government, private and social sector organizations to align their social and commercial goals. In the process, it would also benefit the rural population in remotest areas through IT-based services. The ambitious programme has an outlay of Rs. 23,000 crores. This is coming from the central government over a period of the next five years.

Study - changing demands in rural India

IL&FS was appointed by the Government of India as the National Level Service Agency (NLSA) to implement the Common Service Centre programme. They hired A C Nielson, corporate consultants for a rural service demand survey.

A C Nielsons survey with a sample size of 24,000 people found high willingness to use the following services:

-

Agriculture consultancy

Digital Photos

Health Services

Movies

Photocopy

Railway Tickets Sale of Agriculture Produce

Tuition classes.

Rural India is changing. These demands were unthinkable just a few years ago.

The Common Service Centres therefore aggregates a lot of services. They are expected to provide high quality and cost effective video, voice and data services in e-governance, education, health, telemedicine and entertainment. It can also offer web-enabled services such as download of application forms, certificates, payments of electricity, telephone, water and other utilities.

But mere government services will not be able to sustain the operator of the centre as he needs volumes. Other IT services like printing, scanning, DTP, web surfing, agriculture business information and financial services, would need to be offered to users too.

If the Common Service Centres have to function efficiently, the main challenge for the government is to ensure that infrastructure, connectivity and reliable power supply is in place. It also must have proper trained manpower and management to make the revenue model work.

It is the worlds largest e-governance programme costing over Rs.23,000 crores. Says Arun Varma, vice-president, IL&FS, New Delhi: It is an attempt by the government to demystify governance and take it to the citizens doorstep. After all, accessing land records, obtaining birth certificates and passports, filing income tax returns and getting medical opinion from the countrys best doctors should be as simple as clicking a mouse. And as close as neighborhood shops that you can easily walk to.

![]() e-Gov monitoring in progress. Pic: IL&FS.

e-Gov monitoring in progress. Pic: IL&FS.

Aakansha Rao gave birth to a girl on 15th September 2006 at Raipur in Chattisgarh. Her husband, Venkatesh Rao, went to a Common Service Centre in Chhattisgarh, which is a delivery point on 8th October that year and within minutes got a birth certificate-thanks to e-Governance that is making such procedures easy. The idea is to ensure anytime, everywhere access to information and services across the country. All in all, it is a welfare scheme, which uses technology. It is not a technology programme, but one where technology plays a constructive role to reach easy services.

A Common Service Centre is a rural telecentre-much like a cyber café, that delivers government services like birth certificates, land records, application forms and the like.

Manoj Karmakar of the Sanbandha Gram Panchayat office in West Bengal runs one of these Common Service Centres, setup under the NeGP. The office used to be a deserted place earlier in the late evenings, but now even at eight in the night, students practice working on the computer at his centre. He also does some data entry work for some government departments. The centre helps him earn around Rs.15,000.

However, it is not as easy as it sounds.

When Varma traveled to the interiors of Hazaribagh, Jharkhand, in September 2006 with his two colleague Vashima Shubha to see how Common Service Centres could be set up there, his vehicle was surrounded by Maoists. They told both of them and Sudhir Sinha who was from the corporate world as they were interested in partnering the project, that opening telecentres in remote areas was a ploy to keep the IB and the local intelligence network informed about the activities and plans of the Naxalites. They were told that if they cared for their lives, they should take a U turn and return. It took a lot of talking for Verma to finally convince them that the e-governance plan was to reach services to the common man easily so as to empower them. Then, they were allowed to go and the rest took off from there.

Coming back to Bihar, Chief Minister Nitesh Kumar now wants the state to get into e-procurement and e-tendering so there is complete transparency. It will also ensure there is no cartel formation. It is not that there is no resistance to all this, says Prasad, but we have inoculated ourselves against all resistance. It is only a matter of time that this system of e-governance will be accepted as the only right and just way to govern.