Sambhu Prasad Bin and other fishermen of his community were once expert hunters of Shihu, the Gangetic dolphins (Platanista Gangetic) found in the Brahmaputra. They hunted this unique fresh-water mammal for its blubber, at the confluence of the rivers Gadadhar and Brahmaputra, which is one of the dolphin breeding hotspots in Dhubri district of lower Assam. The Bins also traditionally used dolphin oil extracted from the blubber as bait to catch neriya, a local variety of fish.

Today, however, the Bins have not only stopped hunting the dolphins, but have turned their protectors as well. The fishermen, once branded as poachers and killers of river dolphins, have turned protectors of this threatened species, thanks to a community-based campaign for saving the river dolphins launched by the Center for North East Studies and Policy Research (C-NES), an NGO based in Guwahati. Under this campaign launched three years ago, local groups like the Bins have been brought into the conservation process, by creating alternative livelihood opportunities for them, and also by introducing alternatives to certain dolphin-based products like the fish bait.

In 2007, C-NES facilitated extensive training for four fishermen in Patna, showing them how alterative bait made from fish viscera could be used for hunting neriya, and encouraging them to use this instead of dolphin oil. The alternative fish bait has been developed by Prof Ravindra Kumar Sinha, an eminent zoologist at Patna University. The fish viscera, which is easily available in local markets, is mixed with roasted skin of goat or chicken and coal to concoct an effective bait.

Photo:

Sambhu Prasad Bin (second from left) works as a community worker in different programmes of C-NES.

Photo:

Sambhu Prasad Bin (second from left) works as a community worker in different programmes of C-NES.

Sambhu, who was a member of the group that underwent training, says, "After undergoing the training at Patna, we have locally arranged a number of training and demonstration sessions for the fishermen of our community in Dhubri. Bins live in several parts of the river banks, and the message of this alternative bait has now spread in the entire state. They have totally stopped killing river dolphins now." He adds that the alternate bait is also compraratively cheaper, as every kilogram of fish viscera costs only Rs.20 in the market, whereas one litre of dolphin oil costs about Rs.2000.

C-NES also arranged awareness camps to make local communities in dolphin habitat areas aware of forest regulations to prevent killing of river dolphins. This aquatic mammal, also known as the whale of the river, is protected as a Schedule I species, through the Wildlife Protection Act 1972. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) declared the river dolphin an 'Endangered' species in 1996. Sambhu acknowledges that the awareness camps have also been responsible for ending the practice of dolphin hunting.

•

IUCN page for river dolphins

•

River erosion threatens Majuli

•

Winning against poaching

Manik Barua, who has been associated with the project since the beginning, says that so far more than 50 SHGs - including two entrepreneur groups - have been formed with C-NES's support. The SHGs are engaged in various income generating activities such as dairy, poultry, duck raising, piggery, mushroom and bee keeping. The entrepreneur groups from Kukurmara developed a boat and two cottages for tourists using the grant received by them.

From designing alternative livelihoods for river bank dwellers to making an internationally acclaimed documentary film titled, "Children of the River, the Xihus of Assam" and spreading a massive campaign targeting school-children that ended in a state children summit in Guwahati; the relentless conservation efforts and awareness drives by the Centre has led to the Assam government declaring the river dolphin the 'State Aquatic Animal' on the World Environment Day in 2008. With the declaration, it is expected that the issue of saving habitats of river dolphins will gain attention, as in the case of other important wildlife species including the one horned rhinoceroses, golden langur, elephants, tigers and others, Barua adds.

Promoting conservation

Three years ago, the Rs.30 lakh project, titled "Promoting Conservation: Saving the Gangetic dolphins, Creating Livelihoods, Eco-tourism", was launched with funding from the Ford Foundation. Bhaskar Jyoti Saud, who is in charge of the project, tells India Together that the results have been positive - ensuring alternative livelihood opportunities to the community while alongside spreading the message of saving the river dolphin and its habitats has produced results. The project was aimed at stabilising the dolphin population of the Brahmaputra River by analyzing threats to this highly endangered aquatic creature. Besides Dhubri, CNES identified two other dolphin-breeding locations - Kukurmara in Kamrup district, where the river Kulsi meets the Brahmaputra, and Guijan in Tinsukia district.

Bhaskar Jyoti claims that both Kukurmara and Guijan have since emerged as ideal eco-tourism centers. Kukurmara's proximity to Guwahati, (it is only 20 km from the capital city) has helped it grow into an accesible and popular river dolphin site. It also has one of the highest densities of river dolphins in the state. Likewise, Guijan is adjacent to the Dirbu-Soikhowa Wildlife Sanctuary in Tinsukia district in Upper Assam, which is famous for wild horses, and thus attracts large number of domestic and foreign tourists. The CNES has also been demanding inclusion of both Kukurmara and Guijan in the official tourism map of Assam, so that tourists can get better information about these destinations.

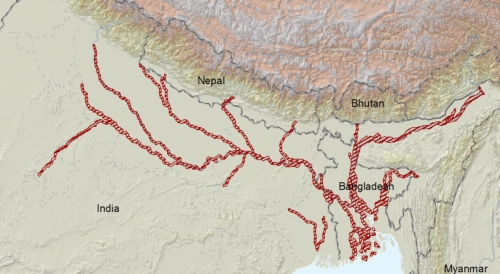

The habitat range of the Gangetic river dolphin in India.

Source: IUCN Red List

The positive impact of these conservation initiatives has also been reflected in dolphin population surveys. A recent survey conducted by Aaranyak, a society for biodiversity conservation in North East India which engaged in a scientific study of river dolphins in Assam in 2008, recorded 264 river dolphins against 250 in 2005. Dr. Abdul Wakid, who is in charge of the Gangetic Dolphin Research & Conservation Programme, told India Together that the river dolphin population in Assam is distributed in the main course of the Brahmaputra, and in two of its tributaries - the Subansiri and Kulsi. The survey revealed an increase in the dolphin population in the Brahmautra's main course (from 197 to 212) and in tke Kulsi (from 27 to 29), but a decrease was observed in the Subansiri (from 26 to 23).

Wakid says further research is needed to say why the population in the Subansiri river has declined. He says that the first river dolphin survey in Assam was conducted in 1993 by zoologist Dr R S Lalmohan, and had estimated 266 of the aquatic species in the Brahmaputra's main course alone. This suggests that the there has been a decrease over the last 15 years or so in the dolphin population, but that recent conservation efforts are reversing this decline.

Saving river dolphin habitats is important, as the presence of this aquatic mammal in a river system signifies a healthy ecosystem. River dolphins are at the apex of the aquatic ecological pyramid, and its presence in adequate numbers signifies greater bio diversity in the river system as a whole. In some ways, this is similar to the role of the tiger in terrestrial ecosystems elsewhere in India. For this reason, says Wakid, the river dolphin is also known as the 'freshwater tiger'.

The Aaranyak research programme has identified several threats to the dolphins - accidental killing while using gill nets for fishing, poaching, habitat loss, food shortages, construction of dams, and the proposed seismic survey to be conduced by Oil India Limited. Constant monitoring and awareness camps have reduced the threat of poaching to a great extent. However, instances of inadvertent killing during fishing still remains as major problem, Wakid says. The gill net the fishermen use is a serious threat; the Aaranyak programme has been working on a solution to this problem by developing improved quality fishing-nets. The programme has also conducted 240 awareness camps in 30 monitoring areas, and has proposed to increase the number of camps to 600 in 2009.

In recent years, the geographic distribution of the dolphins has been more closely mapped, and this is leading to new observations. For instance, the survey has revealed that the river dolphin population is growing in areas where human activity on the river is relatively small. For instance, from the Assam-Arunachal Pradesh border points to Tinsukia in the upper reach of the main Brahmaputra, the population has grown slightly in recent years. However, in lower the reaches of the river, between Jogighopa in Goalpara district and the border with Bangladesh, where the river is used excessively used for both fishing and transportation, the population has dropped between 2005 and 2008.