A few years ago the proceedings of a conference entitled Mahatma Gandhi and his Contemporaries were published. The choice of individuals on whom learned essays were written is fairly representative of English writing on Gandhi. While some essays were on political figures like Ambedkar, JP and Lohia, others were on international figures like Tagore and Einstein. However, with the exception of an excellent essay on Maganlal Gandhi we are left unaware of the many stellar individuals who had thrown in their lot with Gandhi and in turn helped craft his great mission.

The copious historiography and biographical writing centered around Gandhi is preponderantly devoted to either tracing Western influences and antecedents of Gandhi's thought or on the many political figures who were chiefly involved in working with Gandhi towards India's freedom. However it reveals very little of the lives of many who did not bask in the political limelight of the Freedom Movement and instead chose to closely identify themselves with Gandhi's larger agenda and quest for personal and social transformation. Moreover, Gandhi's persona and life-work is also intimately entwined with these individuals, many of whom were his compatriots and fellow-travellers since his early days in Ahmedabad. Their contribution and influence on Gandhi is seldom considered or understood.

Perhaps we can gauge their significance by considering the fact that Gandhi broke his customary weekly silence on only two occasions in his eventful life. The first was when his nephew and creator of the khadi agenda, Maganlal Gandhi, died in 1928. Years later when a compatriot had returned to Sevagram after a heart-attack, Gandhi broke his vow again. "How are you, Mahadev?" he enquired.

Mahadev Desai's relationship with Gandhi is maddeningly hard to classify. While many know him as Gandhi's secretary and recall his name as the translator of Gandhi's autobiography from the original Gujarati, few today have a real sense of the invaluable role that Mahadev played in the life of the Mahatma. Mahadev was certainly Gandhi's secretary and scribe but he was also often a cook, helper, confidant, disciple, companion in jail and ultimately a fellow-traveller, and seeker. More importantly he was an original mind and a leading figure in his own right, a fact that has often been masked by his complete devotion to Gandhi.

![]() An interesting and rare insight into the persona of Mahadev is provided in an exquisitely crafted homage by Verrier Elwin. In 1944, a festschrift was published on the occasion of Gandhi's seventy-fifth birthday and Elwin having fallen out with Gandhi, chose to use the opportunity to write about Mahadev instead! Drawing on his intimate knowledge, Elwin sketched out a wonderful pen-portrait of Mahadev's primary role in presenting the personality and teachings of Gandhi to the world at large. If we have an intimate, fine-textured picture of Gandhi's daily life we owe it to both Gandhi's forthrightness and Mahadev's unflagging diligence. But the unconventional and multifarious roles that Mahadev took on has even Elwin groping for a way to convey a sense of it to the reader.

An interesting and rare insight into the persona of Mahadev is provided in an exquisitely crafted homage by Verrier Elwin. In 1944, a festschrift was published on the occasion of Gandhi's seventy-fifth birthday and Elwin having fallen out with Gandhi, chose to use the opportunity to write about Mahadev instead! Drawing on his intimate knowledge, Elwin sketched out a wonderful pen-portrait of Mahadev's primary role in presenting the personality and teachings of Gandhi to the world at large. If we have an intimate, fine-textured picture of Gandhi's daily life we owe it to both Gandhi's forthrightness and Mahadev's unflagging diligence. But the unconventional and multifarious roles that Mahadev took on has even Elwin groping for a way to convey a sense of it to the reader.

Elwin is possibly the first to air the clumsy comparison of Mahadev as "Gandhi's Boswell" but in the next sentence points to its inadequacy by calling him "Plato to Gandhi's Socrates". However Mahadev was all this and much more.

In 1917, Mahadev Desai was one of the earliest to decide to work with Gandhi. Since the early days in Ahmedabad when Gandhi was groping for a way to transform and transcend the political idiom prevalent in India, Mahadev had become a constant, indispensable figure in Gandhi's highly charged, compressed public and private life. While many hailed Gandhi as the leader of India's political cause, Mahadev had sublimated himself to completely identify with the man called Gandhi. When Gandhi was detained in the Aga Khan Palace in Pune during the Quit India movement, Mahadev chose to accompany him. He was extremely worried about Gandhi going on another fast that could turn fatal.

Instead, on August 15 1942 with his head cradled in Gandhi's lap, the fifty-year old Mahadev Desai perished due to a stroke. In the twenty-five years he spent with Gandhi, Mahadev had left behind an immense trail of selfless service and it's no exaggeration to say that he sacrificed his life for the nation and its people he so loved. As the Gujarati poet Jhaverchand Meghani described him, Mahadev was the rose that blossomed out of the sacrificial fire.

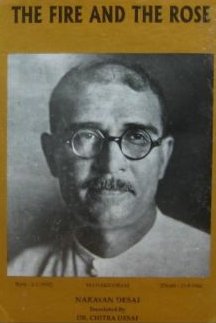

Mahadev Haribhai Desai was born on January 1st, 1892. A century later, his son, Narayan Desai, set out to rediscover his father. The present biography is the result, an intimate, tender portrait of a man and his intensely lived life that went on to win the Sahitya Akademi award in Gujarati. The work is of tremendous significance because of the rare insight it provides into understanding an outstanding and unfortunately neglected figure of our freedom struggle. Since his birth in 1924 till Gandhi's death, Narayan Desai had an intimate, personal relationship with Gandhi which provide a refreshing and often insightful perspective to many an event and anecdote of Gandhi's life that has been chronicled elsewhere by many others.

While written by a doting son, this is no addition to the long Indian tradition of hagiography. Narayan Desai's admiration and warmth for his father is no impediment to a frank, critical appraisal when required. What emerges is a fine, detailed and extremely moving story. Given his proximity to Gandhi, Mahadev Desai was obviously involved in many significant events of his life-time and this biography substantially dwells on these historical episodes. However instead of considering these well-known aspects of our history, in this review we shall limit ourselves to the persona of Mahadev and point to his own individual significance in the large social, political and cultural context of his times.

Soon Mahadev acquired a degree and moved on to studying law as was the norm in those days. To pay for his expenses he took up a job as a translator in the Oriental Translator's Office whose explicit task was the translation of pamphlets and books that could be proscribed or confiscated by the colonial Government! Interestingly we learn that the manuscript of Tilak's famed commentary, the Gita Rahasya, was brought to the young Mahadev for such an inspection. Ironically this was where Mahadev honed his skills for the historic task that lay ahead, the translation and dissemination of the "subversive" works of the Mahatma! The tables were to be well and truly turned.

By the time he finished his law degree in 1913, Mahadev had also acquired a taste for literature and read avidly. And it was during this period that he struck up a friendship that was to change the course of his life. This man was Narhari Parikh who introduced Mahadev to two of his enduring passions - Bengali literature and Mahatma Gandhi.

Now forgotten in the annals of Gandhian historiography, Narhari Parikh was one of the earliest to join hands with Gandhi and played an important role in the running of Sabarmati Ashram in the early, difficult years. While it is common practice to talk of Gandhi's magnetic appeal that irresistibly drew many to his feet, Mahadev's transition into Gandhi's inner circle was actually a gradual process. One of his early meetings with Gandhi was on a curious note. Interested in the substantial prize-money on offer, Mahadev had translated into Gujarati, John Morley's philosophical tract On Compromise. Worried about the correctness of his form of address, Mahadev approached Gandhi to read his covering letter in English to Morley. Gandhi disliked the flattering tenor of the letter and rebuked Mahadev for it.

Both the friends also had long discussions and lengthy debates with Gandhi, most notably on the eleven vows he had drafted for the inmates of the ashram. However it was only after some two years of acquaintance with Gandhi that Mahadev finally decided to take the plunge in November 1917. For a young man who had known years of genteel poverty and was beginning to find his feet in the world, it was a momentous decision. With his father now retired, Mahadev had acquired a job with a bank and was expected to provide the necessary financial stability to the family. On the other hand, Gandhi, not yet a Mahatma, only offered a troubled life and an uncertain and precarious future. In the grand narratives of mass struggles and political intrigue, the conviction and magnificence of such individual choices usually gets left out.

While Mahadev's transition into Gandhi's world may have been gradual, once there his identification with Gandhi was complete. Such total devotion to an individual is quite disconcerting to the modern mind - this reviewer included - where the sanctity of the individual will is deemed supreme. However the cultural ethos of people like Mahadev is somewhat inaccessible to modern-day chroniclers who therefore either deride or choose to ignore it.

Reading through the vast terrain of ideas encompassed by Mahadev one cannot but be humbled by the greatness of a man who was willing to temper and discipline his mind and subjugate its desires and aspirations to a larger cause. Most certainly Gandhi did manage to command such steadfast devotion by his own example. However there is another explanatory factor that is often neglected in the extant literature. While many of the leaders recognised that Gandhi was the political leader who could command the largest following, men like Mahadev and Jamnalal Bajaj were attracted to him for deeper and more personal reasons. They were willing to hitch their lives to that of Gandhi as part of their own spiritual quest - that perennial Indian ideal of moksha being their ultimate goal. The Gandhian innovation was in the idea that salvation was to be strived for by working amongst people and not by living in seclusion.

Soon after they joined Gandhi's ashram, Mahadev and Durga found themselves working in Champaran. From then on until his death in 1942, Mahadev Desai remained the diligent, supreme chronicler of Gandhi's life. It is through his diaries that the "day to day" life of the Mahatma emerges in its full, glorious and gory detail. Mahadev had developed the very un-Indian habit of taking down very voluminous and accurate notes of Gandhi's numerous speeches, interviews, discussions and debates. Many of these were crafted into journalistic essays that appeared in Gandhi's weeklies Young India, Navjivan and later in Harijan. The textile strike of Ahmedabad, Gandhi's failed recruitment attempts in Kheda, the Bardoli satyagraha, and Gandhi's excursions amongst the high-and-low in England are all accurately and lovingly chronicled.

As Elwin perceptively pointed out, Mahadev had "not only a nose for news but a flair for truth". And it is due to Mahadev's accurate description that we can relive the thrill of selling Gandhi's proscribed Hind Swaraj on the day of hartal against the Rowlatt Act. But beyond great reportage, Mahadev's writings also remain invaluable resources that allow us clear insights into the workings of Gandhi's mind and the many pulls and pressures of a very public life.

However, Mahadev was not merely an exemplary chronicler of events but when the occasion demanded it, he was also involved neck-deep in the crafting of the very struggles that he helped record for posterity. The Salt March and the great outpouring of patriotic feeling it unleashed is one well-known instance. On that occasion, with many of the leaders behind bars, like a charming captain he directed the thousands of foot-soldiers in India's struggle for freedom. It must have been a very different time from ours, for Mahadev said in a meeting that "Those who want rigorous imprisonment should go to Bandra and Bombay. Those who want simple imprisonment should go to Viramgam"!

Working with and for Gandhi did not imply that Mahadev's life was just an elating series of uplifting struggles. It also involved a lot of hard work and drudgery. Being Gandhi's secretary, Mahadev had to attend to the many needs of a great man and manage the unrelenting demands made on Gandhi's time. He had to set up meetings, ensure that Gandhi's time was properly utilised, take notes and write letters, edit articles and plan and prepare for the days ahead. Companionship with Gandhi also meant that Mahadev and others had to attend to his personal needs within their limited means and ensure that the ashram functioned according to the strict code that Gandhi had laid down.

The life they chose transcended the ordinary boundaries of a professional or personal relationship and Narayan Desai having himself lived in these ashrams paints an extremely rare and remarkably vivid picture of the demanding but enriching way of life in Gandhi's community. The readers attention is also to be drawn here to a charming volume of Narayan Desai's anecdotes as a child in Bliss it was to be Young with Gandhi. Narayan Desai also gives us poignant insights into the lives of the inmates especially the women. Their marital lives had to be negotiated within the strict confines of an unsparing code and Gandhi's ideas on bhramacharya would certainly have taken their toll. It is unlikely that most women had any choice in these matters and while Gandhi did draw many ordinary Indian women into public life for the first time, it is certainly the case that women like Durgaben did not have much of a say in the major decisions that their menfolk made on behalf of the family.

All of this hardship had a reason. In his belief, Gandhi very closely identified larger societal ills with the weakness of individuals, especially those of himself and others around him. And the iron code of ashram life was as if to put spine into the average Indian. Khadi was another of those great passions and Gandhi thought of spinning as a daily act of expiation. Apart from pointing to its immense economic significance, Gandhi believed that one had to live by the sweat of one's brow and, as Narayan Desai narrates, Mahadev worked hard to excel at his daily spinning.

Subjecting oneself to such a demanding daily regime was part of the preparation for a freedom that went beyond the removal of the British but encompassed the meaning of liberation in all its social and spiritual senses. And their lifestyle choices were indeed not for the faint hearted; for instance there were many days when Mahadev made two round trips by foot between Sevagram and Wardha in the scorching heat of that region, a total distance of some twenty-two miles! However this obsessive sense of the virtuous self and a punishing regime did take its toll and Mahadev suffered from bouts of illness that eventually lead to his early demise.

As mentioned earlier, while there were many who joined Gandhi in the political fight against the British, there were far fewer who were willing to throw in their lot and immerse their lives completely into the larger "experiments" that Gandhi carried out throughout his life. And while bhramacharya was part of an exercise in self-control and beyond, Gandhi's Christian-like innovation of public confessions were an additional part of the merciless subjugation of the individual self and its ego. Mahadev, having volunteered for such experiments and being Gandhi's fellow-traveller and votary was one of the few who were truly part of this process. And it is thus we find him on stage in 1930 confessing to an audience about a "transgression" with "one of the women among you".

Mahadev was a tall, handsome, soft-spoken man and being Gandhi's confidant no doubt enhanced his attractiveness. But some of the relentless desire for truth and candour has also been passed down the family line as Narayan Desai also recalls the incident when one night a charming seductress in Bombay tried to join a young, petrified Mahadev in his bed!

Mahadev had over the years completely identified himself with the cause that was Gandhi - as opposed to Gandhi's cause. This fact is movingly captured by Narayan Desai, when he tries to find himself in Mahadev's diaries : "Exactly sixty-six years after this day the main character of that telegram repeatedly turned the pages of Mahadevbhai's Diary of 24-12-1924 and a couple of days following it, out of curiosity and wonder. There was no mention at all of the birth of a son! Mahadev's diary had fused in Gandhiji's diary." What the son made of this discovery he does not tell us but we can surmise that it was touched with both sadness and pride.

But Mahadev's complete devotion to Gandhi did not make him a blind, unquestioning camp-follower. Gandhi himself demanded that Mahadev be critical of his views, for he wanted a worthy opponent to keep his thinking clear and nimble. Over the years Mahadev proved himself to be both a trustworthy companion and an able debater as evidenced by the correspondence between them. They talked about many things : political choices, the qualities in others, running of their daily lives, and their own personal and spiritual quests. Like many others, Mahadev had vehemently opposed Gandhi's suspension of civil disobedience after the Chauri Chaura incident.

However while most people were interested in Gandhi's political struggles alone, Mahadev was also very clear-eyed about his loyalty to Gandhi and his reasons for casting his lot with the Mahatma. While he was willing to argue with his mentor, Mahadev would only push his ideas so far and no further. Their relationship was one of mutual self-exploration and carried with it the bumps and warts of any real, human relationship. As is tellingly revealed in the selection of letters used in this biography, often Mahadev and Gandhi quarreled like lovers. And like lovers the bonds that tied them together were enduring.

Mahadev's loyalty was most severely tested in 1938 in an incident at Puri. Gandhi had declared that he would not visit any temple that refused entry to the lower castes and thus the famed Jagannath Temple at Puri would be out of bounds for him. After a magnificent misunderstanding Kasturba, Mahadev, Durga and some others visited and prayed at this temple. Gandhi was suitably incensed and suffered from high blood-pressure as a result. Moreover he held Mahadev responsible for the fiasco. Mahadev on the other hand felt that he had got contrarian indications from Gandhi and was simply obeying Gandhi against his own instinct. Confused, angry and tormented at being called to account and unable to argue with an unwell Gandhi, Mahadev decided to write a note requesting permission to leave. In return, Gandhi provided a stinging rebuke and refused to part with Mahadev as he was indispensable! For a long time now, Mahadev's destiny had been inextricably tied to that of Gandhi.

Mahadev shared many of Gandhi's interests but his natural disposition was different. In his early years he was presumed to be a poet in the making and the fine, refined quality of his penmanship was very evident in his writings and excellent translations. As an interesting aside, Narayan Desai narrates the story of how Mahadev was criticised by partisans on both sides for translating Jawaharlal Nehru's Autobiography into Gujarati. Some were appalled that Mahadev was translating the work of a man who was perceived as a critic of Gandhi while others with socialist leanings doubted if he would stay true to Nehru's views in the translation!

An exploration of Mahadev's short life and substantial body of work is both revealing and humbling. Once, when asked sarcastically if there was any similarity between Gandhi and Nehru, Mahadev pointed to their "... burning desire for truth, fierce patriotism and the strength to renounce everything for both of the above principles." But Mahadev himself embodied these values and in his death he redeemed his promise to serve his people by his selfless service to his Master. And as Rajmohan Gandhi points out in his foreword to this volume, after Mahadev's death in jail, "Word of the sacrifice penetrated the Raj's barbed wires and stirred India. Fifty-two years later, its recollection moves us, and puts in their place our grumblings at petty inconveniences today."

In the decades since Mahadev's death, Narayan Desai has proved himself a worthy son of a great father. Taking inspiration from both Gandhi and his own father, Narayan Desai has followed the call of his own heart and invested a new rich meaning in the idea of a public life. Having recently turned eighty his life is itself worth chronicling. In the quiet surroundings of the Sampoorna Kranti Vidyalaya in Vedchhi, Mahadev's sense of dedication and service is alive and well in the lives and minds of his descendants. And it is indeed gratifying to see this in a country where we often see only power, privilege and corrupting influence passed down the generations as inheritance.

Postscript

Despite the immense value of this volume, Mahadev Desai's life awaits many more expositions and interrogations, for beyond his stellar character and charming personality he also encapsulates the ennobling qualities of an age where a grand vision for India and its people throbbed in many a mind. This vision is hailed as grand and uplifting by some and fiercely opposed by others. But at its heart it is supremely creative and inspiring, and in our cynical times there is a desperate need to recover it. Having said that, it is also necessary to point out that at more than seven hundred pages this biography is excessively large and some deft editing and excision of unnecessary extracts could have greatly increased its value and reach.

If Mahadev Desai produced excellent translations, unfortunately the same cannot be said of the present volume and what's worse is the extremely shoddy, unprofessional approach of the publishers. The notation in the book is most unhelpful. Its a difficult task to figure out which parts of Mahadev's letters are quotations from others and where his own commentaries begin. The correct use of quotation marks and italicisation and other conventions would have greatly helped but even minimal editing is woefully lacking. And after a while I lost count of the number of incorrect spellings and other typographic errors. Navjivan Publishing House was founded by Gandhi and many like Swami Anand who ran Navjivan for years took great care and pride in their work. Navjivan would do well to remind itself of its great past for certainly Gandhi and Mahadev Desai would have been distressed at the shoddiness of this volume. One hears that an English translation of Narayan Desai's massive Gujarati biography of Gandhi is in preparation. While we eagerly await its release we also hope that such problems would be suitably addressed.