Much has been said about privatisation of water, for and against. Bangalore is currently at the centre of a seething controversy on the state governments' plans for privatisation. What exactly are the issues with Bangalore's water supply? Where do Bangalore and its surrounding townships stand today?

"Upon completion of construction, water supply O&M (and possibly under ground drainage network) to be done by a private operator through a management contract."

KUIDFC Presentation, September 2004.

"No, O&M privatisation decision has been put off. Privatisation is not part of the agenda." "It [privatisation] is all a rumour spread by some journalists."

BWSSB Chief Engineer 1, January 29, 2006

"We are waiting for IFC to come back with their assessment of the merits and demerits of privatisation But we know that it [privatisation] is not viable at all."

BWSSB Chief Engineer 2, January 30, 2006

"BWSSB has retained IFC to assist in structuring and implementing a management contract with one or more private sector companies to operate and manage... covering the eight ULBs [urban local bodies]. Eventually this private participation is expected to be expanded to include the entire Bangalore City are.. The systems could go to market for bid to private operators by early spring of 2006."

International Finance Corporation (IFC)'s website.

(KUIDFC - Karnataka Urban Infrastructure and Development Finance Corporation;

BWSSB - Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board.)

Confused? Unclear? Welcome to Bangalore's water debate.

•

Mixed results for water reforms

•

Chennai sucking up rural water

•

Ending municipal water shortages

The only certainty in the much debated Greater Bangalore Water Supply and Sanitation Project (GBWASP) is that the waters are murky, muddy and unclear. Metaphorically and literally. The GBWASP project aims to supply Cauvery river water to seven more City Municipal Corporations (CMCs) and 1 Town Municipal Corporation (TMC) 8 Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) in all that currently get their water from tubewells, borewells and tankers and have no waste disposal/sewage collection system. For about 12-13 lakhs of these people, the details of the project are far from clear. (10 lakh = 1 million.)

Ground realities

The eight ULBs that GBWASP proposes to supply and service are the CMCs of Bommanahalli, Byatarayanapura, Dasarahalli, Krishnarajapuram, Mahadevapura, Rajarajeshwarinagar, Yelahanka, and the TMC of Kengeri. They are all on the outskirts of the core city of Bangalore and are relatively new developments. A few of these municipalities are high growth areas, around the likes of Electronic City, Peenya Industrial estate and Whitefield.

![]() Children waiting for water from tankers in HSR Layout, Bangalore. Pic: Arati Rao.

Children waiting for water from tankers in HSR Layout, Bangalore. Pic: Arati Rao.

The state-owned Bangalore Water Supply and Sewage Board (BWSSB) that owns the supply, distribution and water treatment for Bangalore city is also providing surface water to about 10% of the suburban population in the outlying ULBs today. The rest currently get their water supplied from ground water (bore wells, tube wells) and tankers. Formal municipal water supply amounts to no more than about 20 litres per capita per day (LPCD), barely enough on a daily basis to sustain existence for a few months, according to the WHO. This water supply is about four hours on alternate days. Assuming a supply of 140 LPCD, it does not meet demand by a long shot. The aggregate supply-end shortfall is 135 MLD.

The outlying ULBs also have no organized method for sewage disposal or, in some cases, collection. Most of the middle to upper class households use septic tanks for disposal. Even where property developers have provided for a sewage collection system, the disposal is into open drains or valleys and rivers. Disposal from slums and poorer households goes into stormwater drains. Additionally, while almost 80% of Bangalore city's water consumption returns as wastewater (about 570 MLD), wastewater treatment plant capacity is only 403 MLD. The untreated water contributes to contamination of the groundwater, heavily used as a primary source of water supply in the eight ULBs.

Where does Bangalore city itself get its supply from? Primarily from two rivers the nearest is Arkavathi which supplies a total of about 165 MLD and Cauvery, whose waters Karnataka shares with neighbouring Tamilnadu. The Cauvery project is now in its fourth stage, phase 1, and proposes to draw about 100 MLD extra this year from this phase to meet the growing demand of suburban Bangalore. Phase 2 of Stage 4, to be completed by 2011-2014, will then draw over 500 MLD in two installments of about 270 MLD each to fulfill the demand due to increasing population.

However, these projects come at a huge cost to the water board. The total cost for the two phases of stage 4 is estimated to be almost Rs.35 billion (around 750 million USD). BWSSB chief engineers insist that there is enough water in the Cauvery for all this - on good monsoon years -- but it isn't clear how the future of continuing Tamilnadu-Karnataka water sharing will impact this optimism.

Recovering merely the supply costs from tariffs itself appears to be a lost cause to date. Tariffs on water in Bangalore are already among the highest in the country, and are differential in structure, with consumers paying according to consumption. These tariffs, applied monthly, run in slabs, from Rs.6 per kilo litre (KL) for the first 8 KL(reduced from 15 KL), increasing to Rs.36 per KL for the highest slab (75 KL and above) for domestic consumption. Non-commercial users pay Rs.36 to Rs.60 per KL and industrial users pay a flat tariff of Rs.60 per KL. With about 95% of the connections being domestic, tariffs do not cover costs, and a large portion of domestic consumption mainly by the affluent classes who tend to use much more than the urban poor ends up being subsidized. The poor use public taps -- about 7,000 of them around Bangalore -- while the more affluent houses in core Bangalore get piped Cauvery/Arkavathi water.

These pipes have not been upgraded for over 30 years, and an important issue in the supply of water to core Bangalore, or in any city for that matter, is the enormous loss of water to leakage, called Unaccounted For Water (UFW). Current estimates of UFW on existing pipes are anywhere in the range of 35%- 44%, amounting to a loss of around 305 MLD. This is almost enough to bridge the gap in the water needs of the city.

The BWSSB is too understaffed to attend to this. "BWSSB is the leanest of all water boards in the country with just 6 staff per 1000 connections, as compared to Mumbai and Chennai which have 720 per 1000 connections," says Thippeswamy, ex-BWSSB Corporate Planner and Chief Engineer. The BWSSB staff also has no incentive to reduce UFW. The staff is not measured on efficiency of the supply, rather on monthly collections (tariffs) made against connections. As a result, loss due to corroded pipes, damage from digging or even faulty metering goes unaddressed.

Against this dismal backdrop comes the proposal to expand piped water supply and sewerage to the 8 townships, the GBWASP.

How GBWASP came to be

In 1998, BWSSB and Kirloskar Consultants along with the Water and Power Consultancy Organization (WAPCO) published a Detailed Project Report for servicing these eight ULBs. But the project could not be implemented due to lack of financial resources. In 2003, USAID's Financial Institutions Reform and Expansion (FIRE) Project was approached by the Government of Karnataka (GoK) to develop a pooled-finance model similar to the one they had done for Tamilnadu. In association with Karnataka Urban Infrastructure Development and Finance Corporation (KUIDFC, the fund manager), BWSSB (the implementation and planning arm), the Director of Municipal Administration (DMA) and the state government's Urban Development Department (UDD), FIRE prepared a project development report covering water supply and sewerage for Greater Bangalore.

Under GBWASP, 1800 kms of new pipes are being laid for the water supply component. Since current funding, through a combination of sources, is only for the water supply part, sewerage will be tackled after the water supply pipes are laid. Tariffs for this supply to the new ULBs will supposedly follow the existing tariff structure, set and collectable by the BWSSB. All the resources and assets will continue to be owned by the state government/BWSSB, and work is underway.

![]() The Cauvery river, relatively full and flowing, in the 2005 monsoon season.

Pic: shot between Pandavapura and Srirangapatna (Bangalore-Mysore route), Arati Rao.

The Cauvery river, relatively full and flowing, in the 2005 monsoon season.

Pic: shot between Pandavapura and Srirangapatna (Bangalore-Mysore route), Arati Rao.

The proposed extra supply of 100-135 MLD from the Cauvery to these eight ULBs works out to between 61-83 LPCD. This assumes a relatively lesser percentage loss in UFW of, say 20%. At least, this is the assumption made in the FIRE project recommendations upon which GBWASP is based, given new pipes and new meters, etc.

So where is the pain point? There are a few.

Financing GBWASP

GBWASP's financing is from six different sources. The citizens of the 8 ULBs will contribute predetermined one-time amounts as Beneficiary Capital Contributors, the state government will issue 'State Grants,' and the ULBs will contribute through market borrowings and mega city loans. All this for water supply. The sewerage component to come later is being financed separately (see note below.) And for all the financing, KUIDFC acts as the nodal agency.

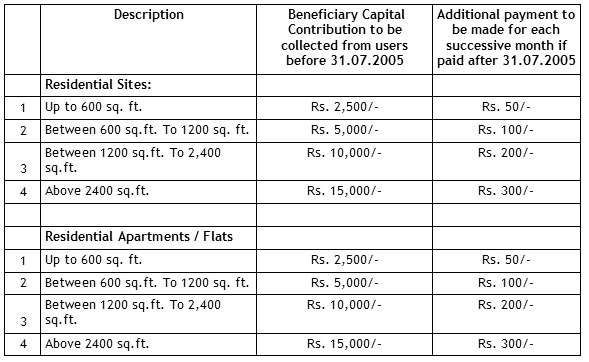

Beneficiary Capital Contributions : The current estimated cost of the water component is about Rs.658.66 crore. Using "innovative financing" methods, the project was to collect almost Rs.180 crores of its financing through "beneficiary capital contributions" from the residents of these ULBs. The "beneficiaries" pay a one-time contribution based on the floor space they occupy, according to the table below that was elaborated in a state government executive order on 9 March 2005.

The above rates include road cutting charges (Rs.1500 for domestic and Rs.3000 for commercial) and does not include access and connection/prorate charges. The catch here is that the "beneficiaries" have to pay up, and many have, without any guarantees of what they are getting or by when. They also have no guarantees of not having to pay again in the future. And paying is no guarantee either of how much water they will get everyday, future tariffs and who will monitor usage.

For the urban poor, purportedly a different slab system will apply. Those living in a floor area less than 150 sq ft. do not pay a BCC. But a comprehensive pro-poor policy, while being talked about, has not been made public yet. "It [pro-poor policy] is there in draft version, the government will have to make the decision and implement. It is not yet decided how the poor people will get service," says a cautious BWSSB Chief Engineer, who spoke under condition of anonymity.

State grants: The GoK will, as per an executive order of 1996 on financing of urban water supply projects, fund 23.3% through a grant.

ULB Borrowings: The rest of the money for the water supply part of the project is through market borrowings to the tune of Rs.100 crores, raised in public bonds released in July 2005 and Mega City Loans of Rs. 46.82 crores (both raised by the ULBs).

The sewerage component: To fund this, GoK would borrow from external agencies talks are on with the Japan Bank for International Cooperation and the International Finance Corporation (World Bank). The 2003 figure of Rs.318 crores for sewerage is to be split between external borrowings (Rs.230 crores) and a GoI grant (ACS Additional Central Scheme). As of now, funding is yet to be finalized.

This is where it begins to go beyond simply being uncertain and get potentially sinister. Some activists allege that when USAID steps in, they almost always recommend and advise on private sector participation (PSP) in municipal services. And sure enough, in the FIRE report, they do mention that given the lean BWSSB, operations and management of these new services can be outsourced through one or two external contracts. Similarly the IFC invests mostly in projects involving the private sector. "The IFC is a transactional Advisor," says a senior BWSSB official. "Their assignment is to assess the demerits and merits of privatisation," he adds. "Let us see what they come back with." And then he hastily added, "But we know privatisation is not viable. Please don't ask me any more questions on privatizations." He spoke to India Together on condition of anonymity.

And yet, the IFC website, KUIDFC presentations, the MoU between the GoK and a Bangalore based NGO Janaagraha, as well as GoK proceedings, all say the opposite. And therein, in the details of implementation and due to the lack of transparency, lies the most angst. More about this later.

Implementing GBWASP

BWSSB ex-Chief Engineer M N Thippeswamy was involved with the water board for eleven years and therefore all the previous attempts at PSP. He is more candid. "The Cauvery waste water plants are all privatised. There is a lot of anxiety on involving the private sector, but Bangalore is not aware of the benefits. A private operator manages his systems more efficiently than the government." He contends that the maintenance expertise and efficiencies gained from private sector cannot compare to that in government. "When a private operator can achieve operating ratios of 0.6 compared to BWSSB's 1.25 today, where is the comparison? As the service area grows and the hiring freeze on BWSSB continues, management of service and assets in-house is, ok, not impossible, but very difficult," says Thippeswamy.

This is where there is least clarity and most noise. As noted in the quotes at the opening of this article, two other BWSSB Chief Engineers denied that the privatisation option even exists on the agenda now.

Regardless, should PSP happen, under what model will the private operator participate? One model, according to BWSSB, is the service option, where the operator will maintain the network bit by bit and not collect any revenues. Another is called the management model. In this, the BWSSB will supply bulk quantity up to a certain, metred, point. After which the private operator steps in to build, maintain and supply the "last mile." The operator will also collect the revenues (tariff predetermined by the BWSSB) and transfer it back to the BWSSB. Connections are determined and sanctioned again by the BWSSB. The incentive for the private operator here is to maintain efficiencies and quality in the system to significantly reduce UFW. "Say the operator reduces the UFW to 12% from the current 40%, then he can then re-sell the saved 28% at a profit. His incentive therefore, is to reduce UFW and deliver maximum water out, as came in," says Thippeswamy.

The question then is who is to decide what the starting UFW percentage each month was? Let's say the BWSSB were to claim 32% starting loss and final to be 20%, then the private operator would have saved 12%. But it could easily transpire that the private operator claims initial losses to be 40% (before he stepped in). He could then claim saving 20% and resell more than legitimate at a profit. The numbers themselves are merely illustrative, and point to a loop hole.

Which leads us to what the operator might do with that water saved from cutting losses. Will the operator be incentivised to provide the last mile to people who can pay little and live in hard-to-reach shanties?

Water for the urban poor

Professor Trilochan Sastry of IIM-Bangalore was one of 50 professors from IITs and IIMs who joined Delhi's activists and residents' associations in demanding and succeeded in the scrapping of expensive water privatisation plans for the capital. Sastry smells a rat in the GBWASP model. "Why will it make business sense for him [the private operator] to service the urban poor, instead of, say siphoning off the water (claiming it as UFW) to more lucrative ends like, for example, the bottled water business?"

And here is where the Campaign Against Water Privatisation (CAWP) is most vocal. CAWP is a coalition of about 40 NGOs who have come together to demand an end to what they see as an anti-poor policy in water privatisation. Any private operator will not have any social or rights-based measure for his operations. For him it will be all about reducing his operating ratio and maximizing profits, they say.

•

Mixed results for water reforms

•

Ending municipal water shortages

•

The privatisation debate

Thippeswamy who is known for excellence in his domain says, "The private operator, should that be the way BWSSB goes, will have several regulators legal, technical, quality, quantity, social and all these regulators will be overseen by a chief regulator." His contention is that a private operator is accountable to himself and it is in his interest to be efficient and competitive. But the fact remains that private operators never see the urban poor as a viable target market.

The urban poor also present a very different and important problem to the four-hours-a-day or water-only-on-alternate-days concept. With the 7,000 free public taps that they used to avail of as and when they required water (subject to there being supply), how will they store piped water under the GBWASP scheme? If the pipes being laid by GBWASP come up to their house/dwelling and currently they have to take care of the plumbing inside will they be able to pay for it? What about the meter cost?

Various officials at BWSSB keep referring to a pro-poor policy that exists, but what it exactly contains and how it addresses these questions is far from clear. That they will pay a BCC proportionate to their house size is known, but how about other costs in the future? Will there be one tap per house or a tap for 5 houses? How will consumption be measured then?

Many of these questions are met with nonchalant "yes, yes, they will be taken care of" or "there is a policy, the government will attend to them" comments from people in the BWSSB, but when participation of the private sector is a possibility, what will govern holding them to their word?

Lack of transparency, lack of information

There are two overarching tones in the debate and planning that has surrounded GBWASP. One, that there is a serious lack of transparency on the side of the government. Little information is forthcoming and while claims have been made in black and white, the government and the BWSSB insist that none of it is a done deal. If one is to believe them, one needs to get honest answers. Otherwise the government's intent in legitimately addressing efficiency, UFW and revenue collection will continue to be under a cloud.

Lack of transparency and frustration at having to wait for answers was one reason that led to the Bangalore based NGO Janaagraha to pull out of its already controversial role within the GBWASP process. Janaagraha had signed up to coordinate the citizen participation plan for GBWASP under a Participatory Local Area Capital Expenditure (PLACE) programme. The NGO was under much pressure to ask tough questions rather than, as some other local civil society organizations put it, act on behalf of the government. Several CSOs held that Janaagraha was endorsing the decision to privatise, and the PLACE document itself stated "To introduce privatisation of O&M" among the objectives of GBWASP.

Janaagraha said it envisioned a 3-tiered pyramid for enrolment and mobilization of the citizens in the 153 wards that span the 8 ULBs. This included for local ward councilors, specialists, representatives of the urban poor and other citizens at each tier to form a citizen steering committee. But when the Help Desk that was supposed to be funded by KUIDFC changed hands and was going to be funded by USAID, criticism of Janaagraha got stronger. Ramesh Ramanathan, co-founder of Janaagraha countered that saying, "We are simply providing a platform in which citizens can engage the process. We do not put forth our point of view on privatisation. We believe that such decisions should be made in consultation with the citizens."

When the government unilaterally announced that privatisation would go ahead in late November 2005, Janaagraha threatened to withdraw, reiterating its stand that any decision on the project must necessarily be made in consultation with citizens, as was agreed in the MoU signed between Janaagraha and the GoK.

The other overarching transparency issue that plagues GBWASP is the lack of clarity around the urban poor policy. When their queries to and clarifications from the GoK on both issues went unanswered for three months, Janaagraha pulled out on 1 February. The group stated that it had interacted with government regularly over the past year, consistently requesting that an urban poor policy for water supply be framed, and that a detailed implementation plan for urban poor coverage in GBWASP be created as quickly as possible. "This has been one of the outstanding issues raised in our periodic reviews. We have also at all times requested for citizen consultation in decision-making processes on this project, and this has not been addressed either, " a Janaagraha release said.

The lack of information and involvement of the citizens remains a critical issue in the process of decision-making. Water supply and sanitation are both too vital to ignore and hard questions stare the 1.2 million citizens of these ULBs. What does the future hold for these burgeoning suburbs of Bangalore then?

The road ahead

The availability of water is key to the survival and sustainability of the Bangalore metropolitan area and its citizens. GBWASP now or not, sustainability is a huge issue. No one knows this better than Thippeswamy. "The year Arkavathi fails, and Cauvery runs low, Bangalore is doomed."

In the meanwhile, governments fall and stall; civil society organizations cry themselves hoarse espousing issues dearest to their hearts and financiers may even schmooze and choose their future pensions. Somewhere along the way, the prospect of real solutions for affordable and sustainable water for all citizens may be getting lost. While CSOs asking questions and protesting lack of clarity are essential to engaging the government, there is a pressing parallel need to move into a solution space for a very real problem that will not go away even if the murky GBWASP project does not go through. Merely scrapping GBWASP that a CSO might claim as a victory might not address the real problem of affordable and clean water that is sustainable.

S Vishwanath, who is an expert on issues of water conservation and integration asks, "Could the South African model be viable? 6000 litres free (per month) for all citizens, pay for what you consume over and above that. Can you [BWSSB] recover O&M costs by increasing the cost of consumption beyond 6 KL?"

Also, it is critical that heavy consumers pay up and subsidizing of water for manicured gardens, washed cars and swimming pools is ended. And all this regardless, another 500-odd MLD may not sustain the Bangalore region as the population grows. One need just look around at the weed-like apartment growth around the city, to imagine what the water resource demands on Bangalore in the next few years will be like. With a population growth rate of about 3.25%, Bangalore's population could easily top 12 million by 2011. Add to this, uncertain monsoons which directly affect availability of river water. Thus the sustainability of even 70 LPCD does not look certain.

What are the options? First, not everything about BWSSB itself may be hopeless. "By all measures, BWSSB is one of the best run water supply boards in India. For example it has one of the most effective tertiary treatment plants, claimed to be the first of its kind in Asia," says Vishwanath. Second, getting the planning right. Bangalore has ground water, rainwater, and access to rivers and lakes surface water. "Efforts need to be made to integrate water supplies from various sources and take advantage of the water cycle in a way that no water gets wasted as it does today," he adds.

To its credit, BWSSB does seem to be thinking ahead. Its website says has commissioned a project to study water management, long term. "We owe it to the country to get our plans right," says Vishwanath, referring to Bangalore and BWSSB.

Else, despite all the financing in the world, water itself may remain a pipe dream.