![]() P. Sainath, whose

intelligent and insightful views on agriculture, caste, media and other matters have

been greatly appreciated by countless readers, has been awarded the 2007 Ramon Magsaysay award for Journalism, Literature, and

Creative

Communication Arts. In selecting him this year's winner, the board of trustees of the Ramon Magsaysay Awards Foundation awards committee "recognizes

his passionate commitment as a

journalist to restore the rural poor to India's consciousness, moving the nation to action."

P. Sainath, whose

intelligent and insightful views on agriculture, caste, media and other matters have

been greatly appreciated by countless readers, has been awarded the 2007 Ramon Magsaysay award for Journalism, Literature, and

Creative

Communication Arts. In selecting him this year's winner, the board of trustees of the Ramon Magsaysay Awards Foundation awards committee "recognizes

his passionate commitment as a

journalist to restore the rural poor to India's consciousness, moving the nation to action."

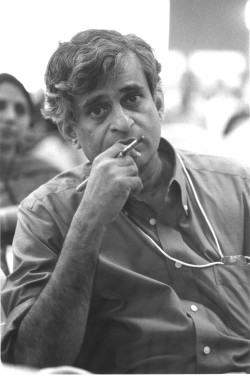

Picture: P. Sainath

credit: Sadanand Menon

In an exclusive interview to India Together, P. Sainath talks to Ashwin Mahesh about his work and his views on trade, politics, society, and the media.

Ashwin Mahesh: This is a serious award for serious work, so let's get straight to it. Does this recognition change anything? Does it improve the chances of the agricultural crisis or caste deprivation or the other things you've been writing about being tackled more purposefully?

P. Sainath: Yes. Recognition of this sort, or by any award, changes a few things. One, it increases the space for such issues. A lot of editors might stop and ask if they too should be giving these topics more attention. Second, it encourages a lot of others who are interested in writing about these things, but are now hesitant for one reason or another, to give it a try. I came from Blitz, as you know. But after I won the Times fellowship, a lot of other people decided to apply for it the following year, thinking that if someone not normally 'in the race' for such recognition is being noticed, they too might have a chance. If you publish 84 articles on poverty, pretty soon everyone else will do some of it too. You've seen how The Hindu's coverage has led to some mimickry of reporting in other papers, even with the Vidarbha series, the Wayanad series, and so on.

•

Write the author

•

P. Sainath - homepage

•

Interviews

•

Send to a friend

•

Printer friendly version

![]() And all this is a good thing. People like me don't have the 'scoop' problem. We don't mind if the things we are writing about are picked up by others, repeated in

other publications, and so on. It's in the nature of the things we write, that we want them to be more written about. And an award always gives that possibility a

boost. That's espeacially good if you're a freelancer, like I've been for such a long time - the scope for getting published jumps when a new space becomes more

inviting to a lot of publishers.

And all this is a good thing. People like me don't have the 'scoop' problem. We don't mind if the things we are writing about are picked up by others, repeated in

other publications, and so on. It's in the nature of the things we write, that we want them to be more written about. And an award always gives that possibility a

boost. That's espeacially good if you're a freelancer, like I've been for such a long time - the scope for getting published jumps when a new space becomes more

inviting to a lot of publishers.

One shouldn't discount the personal satisfaction, either. Obviously, that's a big plus.

AM: Let's move to the issues themselves, and start with agriculture. One hears a lot of people arguing that small and medium farms are simply unviable in the global agricultural scenario. Do you agree? Is there really a model that can work for the small farmer in India, or are we going to see family farms go the way they did in the US?

PS: First off, I think they're wrong to question viability in such simplistic terms. If you consciously develop something, and nurture it, then it becomes viable. What we have is a situation where agriculture in India is being made unviable by imposition. Is American agriculture really viable? You have a situation where cotton crop worth 3.9 billion dollars receives 4.7 billion in subsidies. The Europeans are throwing billions of euros worth of crops into the sea. Whose farming is really unviable? In reality, developed world farming is hugely wasteful, not to forget destructive of soils. And yet, the question is asked if Third World farming, especially small and medium farms, can last in the long run.

•

Ideology of the cancer cell

•

What the heart does not feel

•

India shining, Great depression

•

Growing inequalities

The first kind of argument is plain crap, as I said. It privileges one kind of farming - corporatised production - and lavishes all kinds of goodies and state subsidies on this model, and then questions the viability of others. This is basically the American model. In the US, a 100-odd family farms are going bankrupt each week. Corporate farming, while it is huge, employs hardly anyone. There are 700,000 people employed in corporate agriculture, even their prisons hold three times as many people (2.1 million). So, basically there's an effort to drive people out of agriculture. And in the Third World, this is projected as the way to go for us too. More corporatisation, and more chemicals. By buying this argument, we're turning what has historically been a non-chemical farming culture into a chemical one.

The key thing here is choice. No one is interested in giving the farmers any choice. In Wardha, in Akola, input dealers are saying that unless farmers buy Hi-Feed (a new chemical) they will not supply them urea this year.

The really laughable thing is, it's all offered as part of a 'free market'. I don't see how 4.7 billion dollars in subsidy can provide a free market of any kind for cotton. The US farm bill this year can be summarised in four words - more of the same. And the babalog who've learned their economics from Tom Friedman - not Milton Friedman, but Tom! - are telling us about free markets, and how subsidies like support prices should be abolished. They turn a blind eye to real subsidies, and want to cut 'life support' in the Third World.

There's no such thing as a free market, and anyone who thinks we're going to move agriculture towards a free market should have his brain examined. There's not a single part of the planet where agriculture is not subsidised. So we should end the hypocrisy about subsidies, and begin to talk about who is receiving them, and who should. If corporations are given money as freebies, it's called an 'incentive', and if farmers are given free power in India, that's a subsidy! So what we're doing, by giving money to Cargill or ADM or Monsanto is feeding Frankenstein's grandmother! At least if individual farmers get subsidies, there are some direct social benefits. What's the point of one more private jet to a corporate CEO?

The irony is that more and more people want clean food, not the chemical-contaminated, corporate-produced stuff. In 1984, when I first visited the US, there were only a few small farmers' markets here and there. This year, there were markets that I found hard to enter, because they're so crowded.

AM: But not everyone who questions the viability of small farms is corporatist. I've heard at least a few voices - which you too would recognise as well meaning - question the future for Indian-style agriculture ....

PS: This is the second kind of argument. Let's look at agriculture in terms of livelihood and aspirations. The National Sample Survey data showed that 40 per cent of the people in agriculture don't actually want to continue in it, so clearly they want to move out, they want their children to seek other kinds of work.

But they need options - and these have to be real options, that are available to them without brutalising them first, or depriving them of meaningful choices. If we're not going to do that, but simply try to force them out of agriculture somehow, we may as well be bombing the countryside. We're underfunding development greatly. Look at Utsa Patnaik's work - it shows that in 1989, nearly 15 per cent of GDP was spent on development, but by 2005, this had dropped to six per cent. No wonder that millions of people - neither workers nor peasants - are moving into the urban areas. They can only work in unorganised jobs, where exploitation is easy.

What's the alternative? Let's recognise one simple fact - incomes in agriculture are on average lower than incomes elsewhere. Farmers are really the only group of producers with little or no control over their selling prices - there is simply too much flux globally to determine this. And historically, people have been moving out of agriculture. But we all need to eat. The farmer in the fields is thus making a sacrifice, in terms of opportunity, by remaining in it. We need to first recognise agriculture as a public good, and be comfortable about subsidising this activity.

Take the case of education. There is an estimated under-supply of 400,000 schools. Can you imagine the number of jobs we would create if we decided to address this? Simply having one teacher per class, instead of the current one per five classes, would create two million jobs. The construction of the schools, canteen services for them, and all the eco-systems around each school would create millions of more jobs.

The same with health care. We have a bizarre situation where hardly anyone has basic health care, and we have the fifth most privatised health care system in the world. We have more doctors than nurses everywhere, except in Kerala, where people live longer! There are plenty of jobs waiting to be created in health, but we first have to decide that everyone deserves a fair shot at good health. We're still dithering on that.

Or public transport systems. I don't have to tell you how much work could be created in public transport, if only we decided to invest in its social benefits and actually developed it. We also need to look at manufacturing differently, for a new industrial workforce, for a new generation. Moving people out of agriculture is not the problem, they themselves are dying (literally!) to do this. What we need to do is give them fair livelihood options that allow this change.

AM: Let's stay with agriculture. I want to look at one other thing. In public at least, there are very few disputes that the government needs to take agriculture more seriously. But actual policies for agriculture and agro-trade don't reflect this consensus. Is there a lot of behind-the-doors advocacy going on? I mean, who really wants the government to purchase from foreign traders at a higher price that the domestic support price, or restructure debts that are inherently unpayable, and so on?

PS: Absolutely. Agriculture is one of the largest industries on the planet, and giant corporations control significant chunks of it, leaving farmers completely out of the loop.

Take the case of cofeee. It's almost all produced in the Third World. You can't grow coffee in Alaska. But growers in the Third World have no control over the actual price of coffee. So, you end up with zooming prices for coffee in London or New York while growers are committing suicide in Wayanad! This is because too much of the marketing and pricing is deciding in back-room lobbying in the developed world, and enforced by global trade agreements like the WTO, or before that, the GATT. All this 'green room' stuff is revolting. In nutrition-poor societies in the Third World, we're being forced to grow cash crops, and remain food dependent on developed countries.

Asymmetries of information are everywhere, and denial of information is the game. Jaideep Hardikar, who's written a lot for India Together, is working on some stories on cargo hubs being established in rural areas. You can see that while one farmer has sold his land for 1.5 lakhs an acre, his neighbouring plot, which is owned by a judge, has been sold for 2.5 crores.

AM: But doesn't any of this lose votes? Don't farmers in Punjab punish a government that would rather buy from the Australian Wheat Board than from them?

PS: Yes, but that can be tackled politically. Besides, the Australian Wheat Board buys from everywhere, so it's possible some of this high-priced wheat being bought from them is just re-imported stuff that was originally available cheaper from the Punjab farmer!

AM: Let's move on to society next. A lot of the problems you report on are the result of overall society being a particular way, and politics being of a particular kind. Given that, how do you see any of it changing? What will make politics and society more alert to the socio-economic condition of the majority of people?

PS: Society changes the way it always has. The people change it, either through popular movements and uprisings, or through politics of one kind or another. Not this non-political NGO stuff, that has no chance. We have a situation where the basic building blocks are broken, and we're determinedly institutionalising inequality. It's been designed cynically, and applied ruthlessly, with great clarity and by deliberate choice. It can't go on. At some point, enough people will say 'enough' and then society will change.

AM: You're avoiding the 'R' word ...

PS: 'Revolution' is an over-used, even abused word. We've used this so many times, talking about sleepy villages waking up, that one would think all villagers do is sleep. We can count revolutions in RPM now. I think we need to treat it more seriously, and not use it in a loose-tongued way. Change will happen when some of the basic failures are addressed, however that comes about. India has had many achievements since independence, but we've also had four or five basic failures.

•

The riots and wrongs of caste

•

A much larger house on fire

•

The class war in Gurgaon

We have to address the social issues, there's no doubt of that. But what we have is a situation where even the progressive intellectuals develop feet - and hands, torso, head, everything - of clay when we talk about caste, and start screaming "I've never discriminated against anyone." Or we have rubbish like the AIIMS students agitating, while we're quietly finding out about segregated canteens and so on. We must tackle caste, but we can't tackle caste without tackling land.

There's also gender, regional development, and a few other things. The thing to do is decide the overall lens, and fix what's broken at a high level.

AM: You're a reporter, above all else. So you must see some role in all this for the media. Serious journalism is plain dead in our dailies. I can't remember the last time I saw a full page report on anything, in any paper.

PS: I have said this many times. The fundamental characteristic of our media is the growing disconnect between mass media and mass reality. The other day, there was a lead story, maybe in the ToI, about a guy who paid 15 lakhs to get a private mobile number of his choice, and this was called an 'awakening of india's new confidence'. A couple of days later, it turned out that someone else had paid 1.5 crores to 'collect' 30 such numbers. There's simply no way to describe how stuff like this becomes news, and how it stays in the front pages. I keep thinking it can't get worse but it does.

AM: I have a view that some of this is the result of having 'national' dailies, that aren't adequately rooted in local news, so there's a race to the bottom, in trying to find the lowest common factor and call it news.

PS: You can be national in your vision ... in your idea of what this country is, what its soul is, and still report locally. You can even have several 'local' editions - Eenadu has one for each district of Andhra. Context is what counts, in judging this. Let's face it - 'national' newspaper means something that is published in English in more than one city, that's all. Having said that, national media can draw the threads together from different places, and provide context for local news. A 'wider' perspective, if you can call it that. If the world is globalised, you need that context. A struggle like Plachimada is local, yes, but is it not related in some way to Varanasi?

But there are also gigantic problems with some of the consolidation that we see in media. For instance, there's very little talk of subsidies to media, amidst all the clamour about subsidies to agriculture! You can have big offices in Bahadur Shah Safar Marg or Nariman Point and this is not a problem, but better support prices for farmers are pored over at length. Media are also creatures of the subsidy raj.

There have been two Press Comissions in India, in 1954 and in 77-80 (this commission's term was dragged out by the Emergency). And there has been repeated observation that what we have is freedom of the 'purse', not the press. People have also suggested delinking business houses from news industry.

The monompoly and concentration of power is also a problem. Remember the Bruce Springsteen song 57 channels, and nothing on? What we have is a growing number of channels, but the diversity is limited to the direction of hip movement. On one channel the hips are swaying to the left, and on the other they are swaying right, and it's Prabhu Deva on both channels!

One reason is that the ownership of media has changed. Blitz was family owned, and that provided some foundation, a sense of purpose to having a media organisation. The Guardian is like that, without doubt the best newspaper in the world. It is run by a trust, and that can bring some good foundation.

AM: Anything positive to say about our profession?

PS: There are good things. One simple truth is that the media is regularly administered doses or reality therapy by the people. The best evidence of this I can think of was the 2004 elections, where a whole bunch of disconnected pundits went about telling the public about India Shining, and the people told the pundits what was really on their minds. The next six to eight months were spent by media reporting considerably more seriously. I'd never been as much in demand on television as then ... the media wanted someone to explain to them what the hell happened. And a lot of serious journalists found good work then. You know we've been talking about farmers' suicides since 2001, but it really picked up after the elections went a different way from what the media predicted. Spaces opened up (for reporting) suddenly.

What journalists need to remember is that the public creates the spaces for freedom, and that their readers are almost always far far ahead of the editors. Whether it's the New York Times or ToI, I find that readers write in very seriously. They may take extreme views, even, left-wing, right-wing and so on, but their views are serious, not some flippant stuff.

The challenge for journalists is to create and expand public spaces within increasingly private fora. But we've got history on our side - 180 years of it in this country. Twenty years of trivialsation is a minor period in that larger history. And even within the fluff we see, there is much diversity. In the 80s and 90s, a particular quality of person went into journalism which was good. We're blessed with good young journalists, and there's also a new phenomenon - of people from non-journalistic backgrounds coming into media and bringing a completely different lens, especially online. India Together itself is a great example of this.

Plus, diversity has a way of evening things up a little. I think kindly of the Indian press whenever i am in the US. These two countries - India and America - are the most diverse societies in the world. There are apparently 115 languages spoken in Queens, in New York, a fifth of them might be Indian, even! But look at your American newspaper, and it's essentially a white Anglo-Saxon thing. Diversity is tokenist. In India, thanks to language and culture, there's a much broader sweep of the culture being taken in by the media.

But 'people diversity' is still a problem in India, the Americans have a lot more of this kind of representation. There's not one dalit editor in a major newspaper, and media remains the most exclusionist institution in the country. Our political spectrum is much wider than what you'd think, from looking at the media.

AM: Let me bring this down to the people who actually read you. Do you feel sometimes that the audience for your work has been precisely the same class of people who're so indifferent to larger political realities? I always get the sense talking to you that your 'political' voice is speaking to a different listerner than your 'reporting' voice.

PS: By definition, we're writing for the middle and upper classes. That's going to be true, as long as literacy levels are what they are. Only 20 per cent of families are even getting a newspaper, so you can't get away from that. But I think there are different ways to reach different audiences, and I try to do that. What I write in English is translated into many languages for publication. I also try to communicate with other fora. I rarely speak in Mumbai or Delhi, but in rural Andhra, I'm speaking everywhere, on all kinds of different platforms, most of them small spaces.

•

Great Indian laughter challenge

•

The fear of democracy

•

Can't vote, can vet

As for your question, I'd say I want to reach the middle classes too. I've talked to and taught people from privileged backgrounds a lot, as you can imagine, and I think there's a lot to be gained from this. You know how people in the middle classes talk and read about the 'Invisible India'? That's such a lot of rubbish. Invisible India is the elephant in your bedroom, what we should be talking about is the Blind India that can't see this elephant. And that means talking to the middle and upper classes, speaking plainly about biases, privileges, etc. I want to do that.

AM: Before I let you go, tell us what you're working on now. You're always working on 'series', and there must be something new ...

PS: What I work on is what the situation demands, so in one sense there's no plan. The larger issues of agriculture became important, and I began writing about them. The PM came to Vidarbha, though things aren't any better as a result one year later. But it helps.

I'm also working on a couple of series that are both dear to my heart. One is to create an archive of rural India. I want to use this award to further that. A hundered years from now, many professions will simply be unknown - the streetside knife sharpener, the toddy tapper, the manual irrigator, these will all not exist, and we should record these for posterity. Another thing I'm working on is a series on the last remaining freedom fighters of India. They're dying, and their voices are an important memory of the Independence movement, and that's something I'm looking forward to seeing published and archived. I'm also working on a 'Guerilla Journalism' project, but I'll hold off elaborating on that now ...

AM: Sainath, thanks for taking the time to talk with me. I'm sure a lot of people are thrilled for you. All the best, and we look forward to more of you on these pages, and elsewhere too.

PS: Thank you.