The judgment in the Public Interest Litigation demanding the scrapping of the 97-MW Tashiding Hydro Power Project (or Tashiding HEP) on the sacred Rathong Chu River in West Sikkim, was pronounced on World Environment Day, 5 June 2014 by the Sikkim High Court.

The petitioners in the PIL, both of whom were from the Buddhist minority community of Sikkim, demanded the scrapping of the project, citing violation of the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act of 1991, apart from gross violations of the report of the National Board for Wildlife (NBWL) and the Supreme Court order of 2006 in the Goa Foundation case.

The Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act of 1991, extended to Sikkim in 1998, details a list of sacred shrines, rivers, lakes, caves, mountain peaks and even sacred groves in Sikkim and strictly specifies that no construction or development projects should be allowed to be undertaken in the vicinity of these places.

There is a notification by the Sikkim government that reiterates the provisions of the Act and also identifies the Rathong Chu as a sacred River, along with the Tashiding Monastery on its banks that is deemed ‘extremely sacred’ and revered by the Buddhists.

The judgment pronounced by the division bench of Chief Justice N K Jain and Justice S P Wangdi passed the ball to the court of the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF), asking it to take a final call on the matter within six months from the date of the order.

However, given the recent notifications from the MoEF on the matter of eco-sensitive zones and buffer areas, this judgment does not bring any cheer to those protesting the project on the holy Rathong Chu.

The history of the Tashiding HEP and protests

The genesis of protests against hydro power projects on River Rathong Chu in Sikkim dates back to the mid-nineties, when the Sikkim Democratic Front Party (SDF) government under Chief Minister Pawan Chamling had decided to go ahead with a proposed 30 MW Rathong Chu hydropower project on the River, despite tremendous pressure to scrap the said project, mainly on religious grounds.

Rathong Chu is considered to be a ‘sacred’ river, the water of which is used even today for an annual Buddhist festival – Bum Chu, at the Tashiding Monastery. This has been an important Buddhist tradition since the time of the erstwhile Chogyals (Kings) of Sikkim from the Namgyal dynasty.

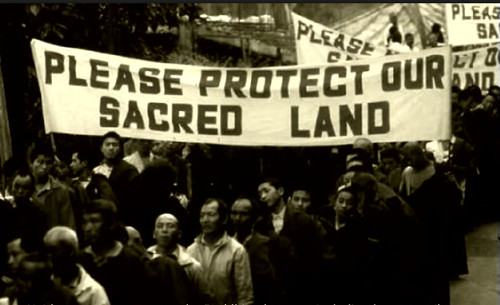

Protests against the original proposed hydroelectric project on the Rathong Chu River. Photo courtesy: SIBLAC

The earliest protests were led by prominent citizens in the state, and supported by Buddhist associations, monks from almost all the prominent monasteries of Sikkim and devout Buddhists from across the state.

Eventually in 1997, under scathing criticism of infringement on cultural and religious rights of Buddhist minorities, the Chamling government decided to scrap the project. Ironically, the same Chamling-led SDF government allotted another project on the River Rathong Chu, a little further downstream, in the year 2006. In fact, the project capacity now was enhanced from 30 MW to 97 MW! While the earlier project was called the Rathong Chu HEP project, it was now rechristened the Tashiding Hydro Power Project.

Regulatory lapses

The Tashiding HEP is presently operating in violation of guidelines issued by both the Central government and the Supreme Court.

According to the Supreme Court order in force in the Goa Foundation case, there can be no construction within a 10-km radius of any national park; the Tashiding HEP being developed by Shiga Energy Private Limited (part of the Dans group), however, falls well within the 10-km radius of the Khangchendzonga National Park.

The MoEF incidentally came out with a draft notification dated 3 February 2014, by which the width of the buffer zone around Sikkim’s lone national park and four wildlife sanctuaries has been reduced from 10 kilometres to between 25-200 metres!

Moreover, while this particular project received Environmental Clearance (EC) from the MoEF on 29 July 2010, neither the project developer nor the state government has obtained statutory clearance from the National Board of Wildlife (NBWL) under the MoEF.

The NBWL standing committee, which sent a fact-finding team to Sikkim in July-August 2013, had in fact warned the environment ministry in August 2013 that at least six hydro-electric projects in Sikkim were coming up without mandatory clearance. These include the proposed Teesta V Project, and the ongoing Teesta III, Dik Chu, Panan, and Tashiding projects.

While clearance has still not been granted, construction activity continues at the project site. The High Court had earlier stated in its interim order in a PIL against the Tashiding project that this would be at the risk of the project developer.

Documents in possession of this correspondent reveal that the Wildlife Division of the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) had written to the Principal Chief Conservator of Forests Sikkim in May 2013, about the status of the Tashiding HEP.

The letter, issued by Mr. Vivek Saxena, DIG Forests (WL), MoEF, sought to know "... whether the construction of the 97 MW Tashiding HEP in West Sikkim is already underway,” and directed, “if yes, the same may kindly be stopped immediately until further orders as they do not have necessary recommendations of the Standing Committee of the National Board for Wildlife." Despite this, construction continued unabated.

Concerned officials in the Forest Department consistently avoided enquiries seeking clarification in this regard. Officials in the Energy and Power Department meanwhile denied any knowledge of the said communiqué, stating that the Forest department had not forwarded any such letter to the Power department.

Protests by civil society fall on deaf ears

Meanwhile, on 20 August, 2014, the president of the Affected Citizens of Teesta (ACT), Mr. Tseten Lepcha served a legal notice to the Secretary, MoEF on the same issue.

ACT is an NGO fighting for the cause of the Teesta River and Sikkim’s fragile environment. The said notice, a copy of which is available with this correspondent, has challenged the draft notification of the MoEF issued on 3 February 2014 as mentioned above. The notice has called for an interim buffer zone of at last 7 to 8 km, instead of the 200 metres as proposed by the MoEF.

The notice also made clear that any failure on the part of the MoEF to reconsider its earlier decision and proceed arbitrarily would compel the ACT to take further appropriate legal action.

The sacred Rathong Chu, waters of which are used by the Tashiding Monastery for the annual Holy Bum Chu festival. Photo courtesy: SIBLAC

In a memorandum to the MoEF, objecting to the same notification, the Sikkim Bhutia Lepcha Apex Committee (SIBLAC) alleged that the proposal would facilitate unrestrained exploitation of natural resources to the detriment of the state's ecology and heritage.

“The draft lacks scientific assessment and overrides the findings of the National Board of Wildlife, which is part of the ministry and comprises a panel of academics,” SIBLAC convener Tseten Tashi Bhutia told this correspondent.

“Any project on the Rathong Chu is not acceptable to us since it is on the waters of the most sacred river according to Neysol and Neyig Buddhist texts. The water of Rathong Chu is used by the Tashiding Monastery for the annual Holy Bum Chu festival,” says Tseten Bhutia, adding that despite so many representations over the Tashiding project and the sensitivity of the issues involved, the Indian government had remained adamant and aloof.

“How can the MoEF decide on the Places of Worship Act and its possible violation?” asks Bhutia, questioning the recent order passed by the Sikkim High Court of the Tashiding PIL.

The angst of the people notwithstanding, with the MoEF notifications in place, the fate of Tashiding HEP and that of other HEPs in Sikkim, operating in violation of environmental norms, appear to be secured favourably as far as the government and project developers are concerned. Environment, ecology, indigenous people, their culture, identity, religion and in fact, very existence have taken a back seat.