Desertification is degrading 12 million hectares of productive land across the world every year, according to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, as 15 billion trees are cut and felled and 24 billion tons of fertile soil goes to the sea. That's 23 hectares lost every minute. This is an area that could produce 20 million tons of grain annually. Already, more than 75 per cent of the earth's land area is degraded, says the European Commission's World Atlas of Desertification.

June 17 is observed annually as a day to review and renew commitments to combat desertification and drought. Global concern over rising desertification is helping to draw much-needed attention to this multi-dimensional issue which affects not only ecosystems but also the people who depend on them. Degradation of land now threatens the food security and livelihoods of more than two billion people in drylands. And in the absence of urgent action, an estimated 50 million more people would be displaced by 2030.

The situation in India

Several studies have revealed that India is facing a severe problem of land degradation. About 96.4 million hectares are considered degraded in the country. The average temperature rose by around 0.7 degree Celsius between 1901 and 2018, according to the Pune-based Indian Institute of Tropical Metrology. Land degradation and poor crop productivity have reduced Indian GDP growth by 2.5 per cent in 2014-15, which is equal to about $73.4 billion. Experts caution that India is likely to suffer from extreme biodiversity loss, a decline in living standards and GDP losses. Several projections suggest that India may lose $1,730 billion by 2050 as a result of climate change.

India covers only 2.4 per cent of the planet's surface area, but it accounts for about 16.2 per cent of the world's population. Similarly, the country has only 0.5 per cent of the world's grazing area but feeds 18 per cent of the world's cattle.

India covers only 2.4 per cent of the planet's surface area, but it accounts for about 16.2 per cent of the world's population. Similarly, the country has only 0.5 per cent of the world's grazing area but feeds 18 per cent of the world's cattle.

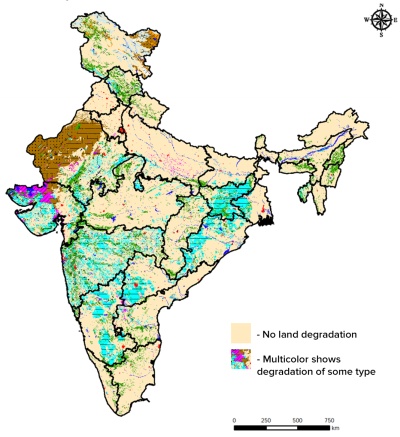

According to the Desertification and Land Degradation Atlas of India, released in 2016, about 30 per cent of land in India faced some level of degradation. The report pointed to excessive application of chemicals and injudicious use of pesticides as prime reasons. Unsustainable use of groundwater is another big contributing factor.

Over the years, land-use change, industrialisation and the ever-increasing climate change have contributed to desertification and land degradation in India, revealed a special report on Climate Change and Land, published by Inter-governmental Panel for Climate Change in August 2019. The report highlights that the increasing frequency of extreme weather events has further worsened food security and nutritional security in many regions. Climate change and intensive farming methods to maximise yields have adversely affected the terrestrial ecosystem. Amidst all these disturbing findings, there are some promising results.

Some achievements

In the past few years, India has reduced 38 million tons of carbon emissions annually. Around three million hectares of forest and tree cover has been added in the last decade. This has increased the combined forest area and tree cover to 24.56 percent of the total geographical area of the country. India restored around 9.8 million ha between 2011 and 2018, as per an IUCN assessment 2018. Thanks to the Bonn Challenge, a global effort to restore 350 million hectares by 2030, there has been an increased focus on the restoration of degraded lands in India.

More than one-third of the increase in the leaf area on the planet can be attributed to China's and India's agricultural and forestry campaigns, highlights a peer-reviewed paper published in 2019. India secured the tenth position among the 61 largest economies that were checked to see if they are on track to meet their Paris pledges, according to the latest report launched by Germanwatch, New Climate Institute and Climate Action Network. But these achievements represent only one side of the story.

Poor governance of resources

India claims that it is doing enough to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, but its poor governance of natural resources is undermining such progress. It is also weakening the resilience of vulnerable people who are confronted by climate change impacts such as desertification and drought. Soil everywhere is less able to support crops, livestock and wildlife. And the pandemic is further worsening the situation.

In a bid to boost post-Covid-19 economic recovery, green options have been largely sidelined. The government has allowed private industries for coal mining. Ajay Sharma, who works on clean energy access with Coolcrop in Himachal Pradesh says, "Instead of focusing on environment-friendly solar plants, the government is encouraging investments in coal-based power generation." Spending on new green energy projects generates twice as many jobs for every dollar invested, compared with equivalent allocations to fossil fuel projects, economists Joseph Stiglitz and Nicholas Stern pointed out in a recent study.

Most of India's green cover is not in forests but plantations which do not help biodiversity. In the guise of afforestation programmes such as the Compensatory Afforestation Fund Management and Planning Authority, non-native tree species have been planted in several places, which threatens the ecology and livelihood of local communities. "Plantation of water-intensive plants such as Eucalyptus and palm is resulting in loss of biodiversity," says Dinesh Suna, coordinator, Ecumenical Water Network, World Council of Churches, Geneva. "This mindless 'green washing' should stop immediately," he adds.

Environmentalists allege that the government is allowing drilling for oil and mining for coal inside the forests as well as in the fringe areas around them that are predominately inhabited by the scheduled tribes and other forest-dwelling communities. Since 2014, the government has approved 270 projects in and around India's most protected areas and eco-sensitive zones for the construction of dams, roads and industries. These high-value forest areas store 15 per cent of global land carbon.

"These projects have aggravated land degradation and desertification situation," said Prafulla Samantara, environmental activist and recipient of Goldman Environmental Prize, adding that Covid-19 pandemic reminds us of the importance of clean air, water, soil, forest and less use of fossil fuel more than ever before.

Sustainable land-use and community participation

"Nurturing healthy soil is imperative to combat desertification," says Nishat Azam, Delhi-based freelance consultant on climate change. We need to promote a living soil policy that will contribute to the country's food basket. Reducing land degradation is key to improving agricultural production, food security and ameliorate poverty, he emphasises.

The adoption of agro-forestry could be a game-changer. Inter-cropping legumes, recycling of farmyard manures and crop residues, nurturing soil with organic fertilisers, nurturing agrobiodiversity, soil conservation, and eco-friendly afforestation would prove vital for preventing desertification. Degraded soils cannot produce a healthy generation. It is high time to make an urgent intervention in collaboration with the local community to ensure healthy soil.

We also need to support Adivasi communities to cultivate their traditional climate-smart crops such as millets, tubers and roots. These crops are pest resistant, less water-intensive and suitable to the local climatic condition. This would rejuvenate degraded land and ensure access to nutritious food. Hence, Adivasi people should be seen as part of the solution of land degradation rather than the main problem as some environmentalists claim. "Through their traditional knowledge and practices, Adivasi and forest-dwelling communities have been engaged in sustainable land use, land restoration and ecosystem restoration for ages," notes Archana Soreng, a climate activist who is also a Youth Advisor to the UN Secretary-General.

Therefore, it is crucial to recognise and enforce legal rights over their land, forest and territories to combat desertification and boost land restoration. Government should protect them as they have been victims of gross human rights violation and atrocities for protecting their forest, land and nature, she appeals.

Pastoralists can show the way

Civil societies working in the Thar desert of Western Rajasthan claim that pastoralists have been conserving biodiversity, enriching the soil and preventing erosion for millennia. "The mobility of their herds significantly prevents overgrazing and allow growth of natural vegetation," says Aakriti Srivastava, lead knowledge support, Desert Resource Centre (DRC), not-for-profit advancing the knowledge systems embedded in desert culture, ecology and economy in Rajasthan.

Picture: Pastoralists traveling with their herds depend on common property resources.

Picture: Pastoralists traveling with their herds depend on common property resources.

Srivastava adds: "Pastoralists can play a vital role in combating desertification. Their herds provide organic manure which boosts soil fertility in thousands of ha of land. This has resulted in developing a symbiotic relationship between farmers and pastoralists." Despite their low-carbon footprint livelihood, pastoralists are facing numerous challenges for their survival as they are on the frontline of climate change. Thanks to national and international authorities such as National Rainfed Area Authority (NRAA) and Food and Agricultural Organisation of the UN for supporting organisations to address these pressing issues.

Urmul Trust, an NGO working in the desert areas of western Rajasthan, has developed a model programme with technical support from DRC for the revival of trans-human pastoralism in Bikaner district. This is done through supporting infrastructure, capacity building, policy advocacy and innovative value chain development. "This model is being designed to be upscaled across pan India with the support of the NRAA," said Srivastava.

Judicious use of water

India is the highest groundwater user in the world, extracting about 25 per cent of the global resources. A huge amount of groundwater is mostly used in industries and agricultural irrigation. However, there has been a lack of initiatives to recharge groundwater. "Imbalance between the use and recharge of groundwater is causing high depletion which is ultimately contributing to desertification," said Shoumyakant Joshi, lead monitoring and evaluation, WaterAid, East Regional Office, Bhubaneswar.

To tackle this challenge, sustainable water conservation and recharge of groundwater need to be focused on. States should encourage utilisation of surface and sub-surface water sources through water harvesting structures, and government should implement groundwater management and regulation acts to monitor extraction and usage, suggested Joshi.

Institutions working with small-scale farmers have been advocating for promoting sustainable rainfed agriculture in rural and tribal areas. About 85 per cent of India's agricultural land is rainfed. These areas contribute 40 per cent of rice, 89 per cent of millets, 69 per cent of oilseeds, 88 per cent of pulses, 73 per cent of cotton and support 70 per cent of the livestock.

"If we aim to protect these areas from further degradation, it is important to upscale watershed projects and support eco-friendly agricultural practices," said Rohit Kumar, program manager, Vikash Bharti, a Jharkhand-based not-for-profit promoting food and nutritional security among the tribal communities. "This will improve soil fertility and replenish groundwater," Kumar believes.

|

Experts working in the desert area have underlined the importance of harmonising traditional water harvesting practices with modern science. Urmul Trust has been promoting a community-based participatory approach in the revival of water harvesting practices in the Thar desert. "This approach is enhancing adoption of proven methods amongst the community people," said Sanket Kumar Tripathy, sustainability manager at the Trust.

Recently, the trust with the support of donors has successfully increased water storage capacity up to 27 lakh litres through construction and renovation of water reservoirs in 179 households spanning 14 villages of Pokhran under Jaisalmer district. Over two years, this has helped families save more than Rs.3 lakhs that they would have spent on purchasing water from vendors.

"As the world is gearing up to restore 1 billion hectares of land, we need to promote an ecological approach to rebuild India's soil health,” suggests Ranjan Panda, convenor of Water Initiatives and Combat Climate Change Network, India. To translate this approach on ground, the country should restore biodiversity, rejuvenate wetlands and water bodies and revamp urban planning that firmly integrates ecosystem. This will reduce the dependency on grey infrastructure. Development interventions should respect nature, and we as responsible citizens must learn to live in harmony with nature."