"Super luxury apartments in the heart of Delhi", screams an advertisement. "Space, modernity, location ... this is urban living at its luxurious best", promises the promotional video. "Strategically located", "only a few minutes from the Central Business District", "the capital's premier residential address", pronounce the newspapers. The apartments come with price tags of Rs.1.8 to 4.2 crores each.

These are the first evidence, though virtual, of the new infrastructure that the government is putting in place exclusively for the 2010 Commonwealth Games in Delhi. The Commonwealth Games Village will occupy 118 acres of the Yamuna floodplains, adjacent to the Akshardham temple. The apartments in question form the residential complex of the village spread over 27 acres, and will host the expected 8500 athletes and officials for the 10-day duration of the games in 34 towers. The residential complex is being built under a 'public-private-partnership' where the government is providing the land and a private real estate developer is constructing the apartments, with rights to sell two thirds of the apartments after their use for the Games. With construction in progress, the developer has already put the apartments on the block.

The Games Village cannot become a premier residential address without superior transport connectivity to the city centre. The government has sanctioned an elevated road over the Barapullah Nullah, passing close to several historic monuments, to connect the Games Village to the Nehru Stadium and South Delhi at a cost of Rs.500 crores. A Delhi Metro line is also being laid to connect the village with Connaught Place, considered the city's business centre. Another developer has been given the contract for a Metro station with a shopping mall at the village site.

The government presents the 'public-private-partnership' model of the Games Village project as clever economics on its part to save public money - it will not have to invest in the village residential infrastructure; on the other hand, it claims that it will even make some profit from its share of the apartments. However, these claims beg the real question. What is the loss to the citizens of Delhi, when public land that has been considered ecologically sensitive and reserved as a green area for over four decades is converted into a private gated community, as the Games Village residences will be after the games?

A priceless natural endowment

The Yamuna has been the defining landmark of Delhi for at least a thousand years; the seven earlier kingdoms of Delhi were basically confined in a triangular area between the west bank of the Yamuna and the rocky tail end of the Aravali hills known as the Ridge. The eighth - the modern city of Delhi - spreads on either side of the river over a 25 km stretch. The river is fed by melting snow in the Himalayas, but also serves as the drain for monsoon rains in its catchments. The flat low-lying areas adjacent to the river on both banks as it passes through Delhi bounded by embankments provide the river with the increased carrying capacity that it needs during the monsoons and allow flooding in a predictable way.

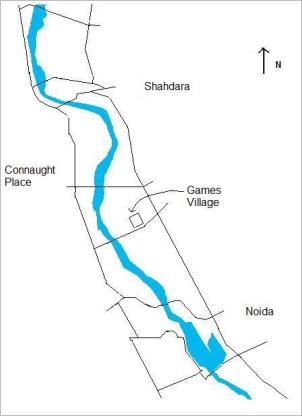

Picture:

A sketch of the Yamuna flowing through Delhi and the grid of roads bridging the river and marking its embankments. The North-South roads on either

side of the river frame the floodplains. (Sketch by the author)

Picture:

A sketch of the Yamuna flowing through Delhi and the grid of roads bridging the river and marking its embankments. The North-South roads on either

side of the river frame the floodplains. (Sketch by the author)

Environmentalists believe that the floodplains play an important role in recharging the ground water aquifers of Delhi, a city already struggling with water shortage and a falling water table. Delhi is a rapidly growing with an estimated population of 17-18 million and declining open spaces and the Yamuna and its floodplains comprising close to 9 per cent of the area of urban Delhi provide a crucial reserve of open space and greenery. Seen against this backdrop, the Yamuna floodplains stand out as a priceless natural endowment of Delhi, to be carefully nurtured for present and future generations.

Planning the future of a river bed

Land use in Delhi is sought to be regulated by a published urban development plan - the so called Master Plan. The 1962 Master Plan of Delhi sensibly designated the Yamuna floodplains as a green area reserved for water bodies and agriculture. But government planners and political leaders always found this land use too restrictive. With visions of Paris on the Seine and London by the Thames, they came up with proposals to turn the stretch of the Yamuna flowing through Delhi into a canal, restricting its width and opening up the floodplains for 'riverfront development'.

A technical study commissioned by the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) and conducted by the Central Water and Power Research Station (CWPRS), Pune between 1988 and 1993, showed up the many risks associated with such proposals. The School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi examined the CWPRS study report and pointed to the enormous investments required, the possible adverse effects upstream and downstream of Delhi and the various constraints to be met, all adding up to questionable benefits. The DDA was forced by the weight of expert opinion to keep the canalisation plans in limbo.

However the idea was never completely dropped by the government. It was simply carried forward in a different way - by changing river bed use in an ad hoc manner from time to time, and by handing over the floodplains for other uses piece by piece.

Constructions were permitted on the floodplains through 'notified amendments' to the land use permitted in the Master Plan - with amendments being made sometimes to legalise a land use change post facto. An amendment, for example, permitted the construction of the massive Akshardham temple on the eastern floodplain of the river in 1999. Another amendment allowed development of a Delhi Metro depot further north of the temple, in 2003.

•

Malls trampling the green belt

•

Port Trust lands in the dock

•

'Street' fight in Bangalore

The crime of the Yamuna Pushta (embankment) residents was that they did not fit with the vision of the state for the Yamuna riverfront development.

In 2006, the land use of the site adjacent to the Akshardham temple that was earlier marked as 'recreational' was changed to 'residential and commercial' and allocated for the Commonwealth Games Village. The plan to locate the Games Village on the Yamuna floodplain was done against the advice of reputed expert institutions such as the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) and the National Institute for Environmental Engineering (NEERI) and in the face of bitter contest by environmental activists and enlightened citizens who came together in the Yamuna Jiye Abiyan.

When challenged by activists on the legality of the decision to encroach on the floodplains, the government scrambled and came up with the environmental permissions and clearances that it did not earlier have - however, the exercise lacked transparency and left grave doubts that pliant officers had been found to give a green chit to the government plans.

In all the controversy over construction in an ecologically fragile area, the government never explained if it had looked for alternative sites for the Games Village and why the Yamuna river bed was the best place.

'Three dimensional development' on the floodplains

The Games Village represents just the thin edge of the wedge in the push to change the land use of the Yamuna banks. Satellite maps clearly show that the bund protecting the Games Village and the Akshardam temple cut the width of the Yamuna eastern bank floodplain in half in that area. This bund will no doubt serve as the new alignment for the Yamuna embankment all along the eastern bank. The precedent having been set, justification of future 'legalised' encroachments on the floodplain will be that much easier, leading to the eventual canalisation of the river.

The proposals for developing the Yamuna zone in the 2021 version of the Master Plan contain new land uses - 'recreational', 'public and semi public facilities', 'transport', etc replacing the earlier ubiquitous mention of 'agriculture and water body'. Given the record of the last 50 years of planned development, it is clear that all that separates one type of land use from a radically different use is a 'notified amendment' that can be passed by the DDA at any time.

The 2021 proposal for the Yamuna zone leaves one in no doubt on this score. We are forewarned that "as development is a continuous process and has to appropriately respond to the needs and aspirations of its beneficiaries, the Zonal Plan does not limit the variety of possible uses" and that "restricted three dimensional development is envisaged in the central areas which have good locational potential (sic) and are either comparatively free from inundation or can be made free from inundation expeditiously and/or at low cost."

Coming back to the question of the games village, why are super luxury apartments needed to house sportsmen for 10 days, one may ask? They have, after all come to participate in competitive games and will presumably be spending most of their time in stadia with hardly time to indulge in the luxury on offer. Could more modest construction not suffice, which could, after the games fulfil the needs of, say, students for hostel accommodation or Indian sportsmen coming to the capital to participate in national competitions?

Just over a quarter century earlier, an exclusive residential complex was built in the name of housing the participants of the 1982 Asian Games in a green expanse that reportedly contained archaeological structures associated with the 14th century Siri Fort. The ultimate beneficiaries of this 'games infrastructure' turned out to be high officers of the government and public sector companies who occupied 70 per cent of the flats built. This time around too, it will not be a surprise to find some of the top hats of the bureaucracy in the apartments retained by the DDA.

In the name of housing Commonwealth Games participants for a mere 10 days, an exclusive gated community is being established on the Yamuna banks, in the heart of Delhi, on invaluable public land that could be developed as a unique public space enriching all its residents. The advertisements tell it all.