Court is a pathbreaking film that looks all set to break records nationally and internationally with awards of every hue and shade. It marks the directorial debut of 27-year-old Chaitanya Tamhane who acted in his first professional play when he was only in Class III. Many years later, as an active member of the theatre group at Mithibai College, which led the inter-collegiate theatre competition, the stage became a natural habitat for his higher education.

Soon, however, he did not like the work that was being done and was inspired by the theatre of Ramu Ramanathan, who came in as a jury member. No one knows exactly how he gravitated to films but with Court, he has become an international name in a kind of cinema we can say, he has virtually invented.

The title Court is almost misleading, in the sense that it is extremely distanced from the metaphorical meanings that attach itself to any film presenting any ‘court’ on celluloid. Even more so, the visual images are far removed from what we recall from our traditional cinematic experience of a ‘court.’

A mainstream film can be a courtroom drama, or a thriller, or a murder mystery, and a hundred other permutations and combinations of several genres put together, mounted lavishly with the froth and frills that forms an integral part of the cinema we are familiar with. Court is different.

The narrative is layered with different sub-plots which by their very nature touch upon contemporary issues creating blocks in our lives, but they are so understated that you hardly notice them. Yet they leave a mark on your conscience and your sub-conscious as you walk out of the theatre. Court is the protagonist of the film, the central character that sucks the viewer into a real life portrayal of what goes on inside a courtroom, how and why.

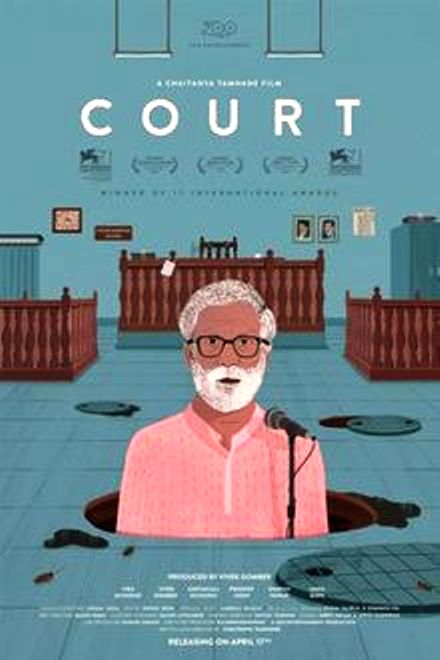

A poster of the film Court

But this needs a storyline and the director provides it through a small incident revolving around Narayan Kamble, a frail and sick man of 65, a performer of folk songs at small functions who makes a meagre living offering tuitions for children. One day, he is arrested during a street performance. The complaint is that he sang a song that drove a sewer cleaner in the neighbourhood to commit suicide inside a sewer. The complaint adds that his songs, written and composed by him, are filled with unmentionable obscenities and incendiary lyrics.

Narayan Kamble is not even aware of the existence of this sewer cleaner. There is no proof that the cleaner knew Kamble or had heard his songs. Till the end, the audience, the court and the entire legal and judicial fraternity within the film remain in the dark about whether the sewer cleaner had committed suicide or had died of suffocation and lack of proper protective gear at work. Yet, Kamble is sent to police custody all over again after he was granted bail earlier on a surety of Rs 1 lakh paid by his defence attorney.

When the defence attorney requests the judge to allow bail as the man is quite sick and the court will go on vacation the following day, the judge simply asks him to go to the higher court which will not be on vacation!

Roots in society

“The idea for the film occurred to me in 2011, after I had finished travelling to festivals with my debut short film, Six Strands. I thought of presenting a realistic courtroom drama in an Indian setting. But where would the funds come from? At this juncture, Vivek Gomber, my friend from theatre and one I had worked with earlier, stepped in to produce and I began writing the script,” says Tamhane.

The film repeatedly draws attention to protracted legal proceedings that adversely affect ordinary citizens both mentally and financially. Debabrata Sengupta, one such citizen, says, “The inordinate delays in the disposal of cases have resulted in considerable backlog of untried cases. Even though much work needs to be done; courts in India are shut for a long period during the year. Could the activities of the Indian courts be brought under the ambit of the Essential Services Maintenance Act? This might speed up the process of delivering justice.”

Another reason for judicial delays is the snail’s pace at which proceedings progress, partially due to the disparity in the ratio between the number of judges and the population.

A very recent judgement passed on four teachers of a West Bengal school underscores the relevance of what Court, the film spells out. On 21 April, the Calcutta High Court directed the education department to reinstate four teachers who had been removed from a Bankura school 17 years ago and clear their arrears. A division bench of Justices Tapen Sen and Siddhartha Chatterjee passed the verdict upholding an order by a trial judge of the same court. The bench also asked the education department to remove the four teachers who had been recruited in place of the petitioners and ordered them to refund to the government the salaries they took for 17 years!

The power of understatement

Court, however, does not point accusing fingers at corrupt practices that delay judgement or try to raise slogans against wrong judgements and unfair practices. Tamhane lets the film speak for itself and underscores the lacunae in the legal, the police and the judicial systems as they stand today and have stood for decades.

It is the very ‘ordinariness’ of the story-telling strategy, the acting by an almost entirely amateur cast, the precise attention to physical detailing of sets, the interiors of different homes reflecting the social class the respective dwellers belong to as well as of the courtroom itself, the brilliant camera that moves into some of the narrowest bylanes of dilapidated Mumbai chawls moving back and forth from and to the court, and the powerful songs lip-synched by Kamble and rendered by Dalit activist and singer Sambhaji Bhagat (who also wrote and composed them) that makes Court suchan extraordinary socio-political statement on celluloid. A statement on how the police, the legal and the judicial systems are structured to work against the best interests of the litigants and others.

In Court, the different layers of the narrative are incidental to the court story. Nutan (Geetanjali Kulkarni), the prosecution attorney, is well-versed in law but goes back to her existence as a middle class wife and mother as smoothly as she argues her cases in court. Glimpses of the family watching television as she cooks and serves dinner, going for an outing to have lunch followed by a visit to the local theatre provide small bytes to the characters that make them identifiable and real.

Vinay Vora (Vivek Gomber), the defence lawyer is affluent but runs an NGO and not only takes up Kamble’s defence for free, but also pays the bail fee of one lakh. He has a flat of his own but often visits his parents in another part of the city, takes them out to lunch, visits bars with his friends and cries silently when two members of an ethnic tribal group bash him up for what they interpret as having insulted their tribe during a court hearing.

The violence is suggested and not articulated. Judge Sadavarte (Pradeep Joshi) an ordinary, upper-middle-class man goes off on a holiday to a luxury resort with a group on the day the vacation starts and keeps dozing off as the children are playing.

Kamble (Vira Sathidar), on his part takes everything in such stoic silence and lack of reaction that it is difficult to match him with the image of the rebel poet (lokshahir) whose compositions and renditions of folk songs arouse awareness among working class communities in Mumbai.

“I never decided to make my film a social or political comment. I wanted to tell the story that I wanted to tell. It wasn't as if I had set out to make a social comment. I started researching on it. I began visiting the sessions courts and discovered that the way the legal system and the courtroom proceedings have been shown in our films are completely contrary to reality, and that comes across in the film,” says Tamhane.

Chaitanya Tamhane, the director

Over 2000 non-professionals auditioned for the acting cast of Court. Non-professionals were auditioned for eight months as part of a quest to find actors who would be as real and identifiable as the script needed them to be. The only two real actors were Geetanjali Kulkarni and Vivek Gomber, both with a good track record in theatre. The technical crew is also fresh because Tamhane did not wish to work with technicians who were used to the usual techniques of cinema as it was his first full-length feature film too.

For editor Rikhav Desai, Court is the first fiction film of his career. The production designers Somnath Pal and Pooja Talreja had never done production design for any film before Court. The sound designer Anita Kushwaha had also worked only in documentary films while cinematographer Mrinal Desai has shot only a couple of feature films before Court.

“For me, this worked very well because I am not trained in any film school myself, nor have I assisted anyone in films. My experience is limited to just one short film and I was as raw as my cast and crew,” Tamhane sums up.

Awards and recognition

Court was the surprise package that bagged the award for ‘Best Feature Film’ at the 62nd National Awards 2015. It also won ‘best film’ in the Orizzonti section as well as the Lion of the Future ‘Luigi de Laurentiis’ award for a debut film. It also won prizes for the best film and best director at the 17th Mumbai Film Festival in 2014, and special jury mention for the ensemble cast alongside other prizes at Antalya, Vienna and three other festivals.

The citation at the Mumbai Film Festival states: “By breathing new life into the genre of procedural courthouse drama, Court paints a complex and moving portrait of daily life in an India that struggles to balance humanity with bureaucracy. The jury was unanimous in its admiration for the naturalistic performances, the sophisticated storytelling and the meticulous direction that combine to raise this film to the highest level of contemporary filmmaking.”

In the final analysis, therefore, Court sets a great example in a kind of cinema we have never witnessed before. It stands by itself, proud and tall by virtue of its own quality, form, content and narrative strategy defying comparisons with other out-of-the-box films.

The pace is slow but the editing cuts a scene short when it is no longer necessary to drag it, such as the theatre scene that shows a part of a comic play and cuts to a laughing audience. Or, in the scene where the judge dismisses a lady appellant because she has worn a sleeveless dress which violates the decorum and rules of the court, or the silent shots of the defence lawyer picking up expensive drinks from a posh shopping mall, sitting alone at his flat, drinking and watching television.

Court sets a moving celluloid statement that reminds the viewer strongly of the constant tussle in between centrifugal and centripetal forces as defined in science. Centrifugal force (Latin for "centre fleeing") describes the tendency of an object following a curved path to fly outwards, away from the centre of the curve. But it is not really a force, it results from inertia — the tendency of an object to resist any change in its state of rest or motion. This is the ‘force’ that the court represents.

Centripetal force is a real force that counteracts the above and prevents the object from "flying out," keeping it moving instead with a uniform speed along a circular path This is the ‘force’ represented by the people who keep waiting for their cases to be resolved, for the date of the next hearing to be announced, for the case to be referred to another court till the petitioner falls sick or becomes old or just dies.