Lalit Vachani is a filmmaker whose creations don't conform to any standard themes in pursuit of fame; after he received his master's degree in communications at the University of Pennsylvania, he produced works such as The Starmaker (1997), a film about the business of "star making" in the Hindi commercial film industry. Two of his films - The Boy in the Branch (1993) and The Men in the Tree (2002) - explored the carefully cultivated and choreographed fascist indoctrination by and within the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). While the former explored the indoctrination of four boys being trained by the RSS, in the latter film he returned to find out whether the same boys have moved away from the RSS and if they have, how they have been doing.

More recently, Vachani's interests have led him to make movies about the Jana Natya Manch, the street theatre group with definite Leftist leanings founded by the late Safdar Hashmi. Natak Jaari Hai, which Vachani made last year, is a nostalgic journey into the struggles, evolution and commitment of the Manch, also known by its acronym Janam founded as an off-shoot of the Indian People's Theatre Movement (IPTA).

"The questions that I wished to explore for myself were What motivates them? What is their vision of change? In what way have they functioned after the assassination of their founder-father Safdar in January 1, 1989?"

Natak Jaari Hai offers at different points along its 84-minute footage, glimpses of scenes enacted from other Janam plays such as Halla Bol, Who Bol Uthi, Yeh Dil Mange More Guruji, and so on. The film moves back and forth through time, space and people, offering priceless vignettes into the character and persona of the late Safdar, through archival footage where he belts out a line of song, joking about his actor's total lack of voice, tune or rhythm. Molosyahree, his widow, opens out her album of black-and-white photographs, and in so doing, essays her evolving relationship with Safdar that physically may have ended with his violent death in 1989 but has reached far beyond questions of mortality through the sustenance and growth of Janam. Malashree recalls the precise date when the last portrait of Safdar was taken, without emotion in her voice.

But the film is not about Hashmi. It is about the movement he triggered during his lifetime; a movement he died for; a movement that lives on much after his death. The film begins with black-and-white shots of two famous Janam plays, Machine and Aurat, portrayed specially for the film, suggesting some of the turning points of the biggest street theatre group in the northern parts of India. Machine was a milestone in Janam's movement becuse with this play, Hashmi and his group stepped from proscenium to street theatres and surprisingly, became a big hit. The play satirises the mechanisation of the humn worker who is reduced to a machine by industry and industrialization.

As the mechanical voices emerge out of the man-machine in Machine, with arms and legs turning into nuts, bolts and wheels, one finds it scary, suggestive of a scarier future. "Having to film a street play on the proscenium turned out to be almost a disaster during the shoot," says Vachani. But on film, it immediately captivates the audience.

"I was actually interested in making an archival documentary on the Indian People's Theatre Movement (IPTA) and Janam was to be part of this larger whole. But then, I found that if I were to explore both IPTA and Janam, I would have to make two films, and not just one. The India Foundation for the Arts offered funding for one film and I opted to do it on Janam, picking the title from one of their plays performed in 1991," says the soft-spoken Vachani. "I had met Sudhanva Deshpande and Mala earlier but beyond that, I did not know the people working within the group personally. At St. Stephens, where I studied, Shakespeare was more popular than Safdar and his plays. The questions that I wished to explore for myself were What motivates them? What is their vision of change? In what way have they functioned after the assassination of their founder-father Safdar in January 1, 1989?"

Sudhanva, one of the actors, says "there are no easy answers," and we are almost sucked into the movement as the camera pans over the travelling journeys of the group through rough roads, performing just anywhere street corner, street square, a slum, a chauraha, creating its own space to throw its collective voice out to those it wishes to reach the masses. Vachani talks to almost everyone within the group. Uttam from Murshidabad approached them with stars in his eyes. "I had great dreams of becoming a film star. I always thought acting meant glamour and money and fame. But I stayed on to strip myself of these dreams, and have become one with Janam," he laughs. "I am more interested in the questions and issues raised by the plays rather than the group's political associations or ideological stance," says the young Sarita who joined the group after having attended a theatre workshop conducted by Janam in her college. "So long as the issues are relevant, the ideology blends into it," she sums up simply.

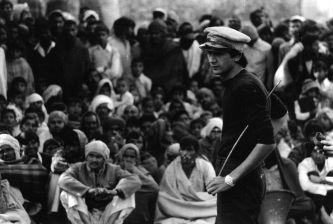

![]() By the time of Safdar Hashmi's death, Janam has given over 4000 performances of its plays.

By the time of Safdar Hashmi's death, Janam has given over 4000 performances of its plays.

Vachani creates some touching moments without sentimentalising them, as when he takes us back to where Safdar was chased during a peformance of Halla Bol and was later beaten up with lathis and rods. The politics of many of Janam's plays invited anger from many quarters, understandably. And Hashmi was eventually killed because he dared to stage a street play on behalf of the Centre of Trade Unions about the government's repression of workers' organs for economic struggle. The play challenged the then-ruling party's mafia politics in Delhi's slums; during the performance, Mukesh Sharma, a Congress-backed independent politician contesting the Ghaziabad municipal elections, and a crowd of supporters arrived at the scene, armed with guns and bamboo poles; Safdar was seriously injured in the confrontation that followed, and died the following day. 10 of the 14 accused persons were eventually convicted of the crime, after a lengthy trial lasting 14 years.

Interestingly, Vachani has shied away from the politics of the movement and has instead chosen to focus on its existence at present, its evolution and its sustenance. Did he show the film to Janmat workers after he had completed it? Yes, he did. "They said they had certain difficulties with my interpretation but they did not ask me to change anything. They felt I was overvaluing their association with the Left." The red flag does make its appearance during some of the plays and the Leftist stance is visible right through the film. Yet, there is no propaganda in or through the film, for or against the group. Vachani tries his best to maintain an objective distance, and quite surprisingly for the crusading filmmaker that he is, he succeeds.