Hyderabad & Anantapur: With lapsed insurance policies costing farmers in Andhra Pradesh crores of rupees, calls for their renewal have begun. Over half a million policies have lapsed in just 36 months from April 2001. The State's bankrupt farmers simply cannot keep up with payments. This period was also marked by hundreds of farmers' suicides.

The Andhra Agriculture Minister, N. Raghuveera Reddy, is keen to see the revival of the policies. Mr. Reddy, who inherited a desperate rural crisis from his predecessors, says the State will do all in its power to help the process forward. "These are farmers who have suffered for the last many years," he told The Hindu . "We appeal to the LIC and the Centre to join hands with us to bring these policies back to life. We ourselves will do everything we can."

![]() Picture:

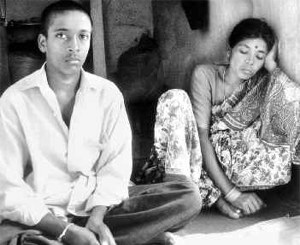

Economic distress, which drove thousands of debt-trapped farmers to suicide, also led to the lapse of lakhs of life insurance policies in Andhra Pradesh. Anjamma and Srinivas, mother and brother of Baja Ramesh who took his life in despair over debt in Medak district. (Courtesy: The Hindu; picture by P.Sainath)

Picture:

Economic distress, which drove thousands of debt-trapped farmers to suicide, also led to the lapse of lakhs of life insurance policies in Andhra Pradesh. Anjamma and Srinivas, mother and brother of Baja Ramesh who took his life in despair over debt in Medak district. (Courtesy: The Hindu; picture by P.Sainath)

"These are people who have lost their ability to renew in a situation of great distress," says the All-India Insurance Employees Association (AIIEA) president, N.M. Sundaram. "The rules should not be used to punish them." There are other problems too. "The incentive for agents to seek renewals declines with their falling commissions each year," says a senior government official.

For instance, on a premium of Rs. 2,000, the agent gets his best deal Rs. 700 (35 per cent) in the first year. In the second, it is only Rs. 150. By the fourth, he is getting just Rs. 100. "Hence," says the official, "he has no incentive to chase farmers to keep up with payments." In fairness to the agents though, even if they had persisted, the farmers were clearly in no position to pay.

Either way, it is in the LIC's interest to revive the policies. For one thing, its clients need it. For another, the LIC makes money on these policies only after the second year. The first two years the money goes mostly for commissions, administrative and processing expenses.

New policies

Meanwhile, things are worse for those who would like to take out new policies. The minimum policy value they have to go in for now is Rs. 50,000 against Rs. 20,000 earlier on. "This happened after the UPA Government came in," says an LIC staffer in Anantapur. The measure places insurance cover beyond the reach of poorer sections.

The NDA Government, too, made it worse for the rural poor. "Earlier," says one LIC Officer, "we had the Landless Agricultural Labour Group Insurance (LALGI). This gave free cover and Rs. 2,000 for any family of this class that lost its breadwinner. This was scrapped by the NDA."

A fax to the LIC Chairman on these issues drew an official response. A reply from the LIC's Executive Director, Central Office (PR & CC) names "... other schemes (that) have been launched" in lieu of this one. And asserts that these too "are subsidised schemes for which a social security fund was created."

Pressure

It is not clear how any of this offsets the loss of LALGI. And the LIC is silent on why it was scrapped.

The ending of the scheme was strongly opposed by the AIIEA. "Generally," says Mr. Sundaram, "the LIC has come under pressure of a very unfair competition. Private insurance providers would never touch the poor sections that the LIC covers.

Gender bias

The Common Minimum Programme (CMP) of the UPA Government says the regulator will ensure that private providers, too, fulfil their social obligations. But nothing has happened so far. With those providers free to concentrate on the profit-making top end of the spectrum, the LIC finds itself at a disadvantage. Yet, scrapping such schemes is wrong."

Some schemes also have a curious gender bias. For instance, the Jana Raksha policy. "This is one scheme," says the Ananatapur LIC staffer, "that still allows policy holders a lower minimum value. Rs. 30,000 as against Rs. 50,000. However, it is only for those below the age of 40. What's more, illiterate women and widows are excluded. However, oddly, illiterate men are not."

The official LIC response is that: "There is a certain amount of moral hazard in insuring illiterate women, considering that the position of such women is not very enviable." Indeed, the LIC argues that these exclusions are made "for the safety of such vulnerable people." And that the "LIC too has done so taking relevant aspects into consideration." Curiously, there is no moral hazard associated with insuring illiterate men and widowers.

"This is absolutely archaic thinking based on outdated practices," says Mr. Sundaram. "Some aspects are not clear, but this whole approach is quite wrong. It smacks of a gender bias."

The LIC says it has "increased the minimum sum assured marginally" for "many of its plans." That is, "from Rs. 30,000 to Rs.50,000." The Corporation says it did so bearing in mind the nature of India's insurance market, the low level of insurance penetration here and "keeping certain other parameters like inflation etc. in consideration."

Special campaigns

Can LIC act to protect farmers in dire straits? The Corporation's official response suggests it can. "LIC floats special campaigns for revival apart from the regular revivals which are facilitated all through the year." It also points out that "normally between November and January, special rebates are given on the late fee/interest portion." It lists some relaxations, including "waiving of medical reports etc., on certain policies subject to certain conditions."

Which is encouraging. Except that any revival scheme needs the Government and LIC to act first. The bankrupt farmers are in no state to move on this individually.

Also, the `special rebates' presently have a meagre limit of Rs. 250. Only a waiver of all dues will enable people to revive their policies. Since there are quite a few grounds on which the Andhra Government, the LIC and the AIIEA do agree, swift action on this front could revive policies worth crores and crores of rupees. A major benefit to farmers in big trouble.

"There can and should be special, even new, revival schemes for policyholders wanting to reactivate their insurance," says Mr. Sundaram. "It should be possible here, as LIC will be dealing not with individuals but a whole group of people. The LIC can waive certain requirements, such as interest for example, if that stalls renewal. The All-India Insurance Employees Association will articulate and press this demand with the LIC and the Government of India." (Courtesy: The Hindu)