At nine in the morning, holding her two-year-old daughter, 28-year-old Nalini Selvaraju of the SC (Schedule Caste) Colony in Belur, waits for the arrival of actor-turned politician Divya Spandana, aka Ramya, the Congress candidate from the Mandya Lok Sabha Constituency in Karnataka.

Expecting better roads, drainage connection and better access to politicians, Selvaraju and others pin their hopes on Ramya for her ability to influence as a popular actor. The education level of the contestant or the questions raised by her in Parliament over the last term matters least to them.

“What they (MPs) do in Delhi does not matter to us. For us, local issues are important and we expect the candidate to influence the local leader to solve the villagers’ problems. That is how we can connect with the MP,” Selvaraju said.

Ramya, who is contesting the second time from the same Lok Sabha constituency, is crammed into a vehicle full of men – her party workers, who, thanks to her personality cult, get into a fight within minutes of her coming on board over who should stand next to her. As Ramya struggles to even stand and looks for support from her female companions, the villagers feel pity for the woman candidate and hurl abuses at the male politicians.

“Being a woman politician in a male-dominated political arena is quite difficult. It is a challenge where one has to work extra hard to remain in the fray,” says the actor-turned-politician.

Ramya had not asked for a ticket from the Congress party when she contested the elections for the first time last year. The party had offered her one because of her close connection with the erstwhile Chief Minister S M Krishna and the popularity she enjoys as a face from filmdom. Such is the case with many women aspirants who manage to get a ticket mainly because of their fame and political connections.

However, there are some who contest elections on their own without any political or financial support. For instance, in Kerala, while mainstream political parties have not given tickets to any women aspirants, Syamalakumari is contesting independently with zero assets (as per the affidavit filed) from Thiruvananthapuram against Union Minister Shashi Tharoor.

According to the 2011 census, women comprise 48.27 per cent of the total population; in 2014, around 47.62 per cent of the voters are women. However, in the Lok Sabha, while women’s representation has shown an increasing trend over the years, it has remained disappointingly low in absolute terms, never exceeding 12 per cent.

As per data from the Election Commission, women’s representation in the Lok Sabha increased to 11.23 per cent of the total 543 seats in 2009 (15th Lok Sabha), from a mere 3.5 percent in 1977 (Sixth Lok Sabha). Even between 1980 and 1984, when the country was headed by a woman Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, women’s representation in the House was only about five per cent.

According to a report from the Inter-Parliamentary Union, an international organization of parliaments, as on 1 February, 2014, India is listed at 111th spot, among the 189 countries in terms of the ‘percentage of women in national parliaments’—much below its neighbouring countries Pakistan, Nepal and China.

Literacy and women empowerment

A lot has been said about what literacy and education can do, in general, for women’s progress. While one could speculate on whether higher literacy would result in the empowerment of women politically, data from past elections show that literacy rates do not play out in the form of better women’s representation. In high literacy states, the pattern indicates that mainstream political parties, under whom the winnability percentage would be higher for a woman candidate, do not allocate enough tickets for women aspirants.

For instance, in Kerala, where literacy rate is the highest in the country (94 per cent), there were only four women contestants in 2009 for the 20 seats from all the three major national parties – the CPI (M), Indian National Congress (INC), and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). During 2004 and 1999 there were just three contestants.

Similarly, in Tamil Nadu where the literacy rate is roughly 80.1 per cent, there were only eight contestants from the major political parties (State and National DMK, AIADMK, INC) for all 39 seats. It was seven and four respectively in 2004 and 1999.

In contrast, in the state of Bihar and Rajasthan where literacy rates are much lower, the number of women contestants from the mainstream political parties are higher than in Kerala and Tamil Nadu. It was 12, 7, and 6 contestants from Bihar for all the 40 seats (54 in 1999) during 2009, 2004 and 1999 respectively, belonging to the BJP, Rashtriya Janata Dal, INC and Janata Dal (United). Likewise, there were 9, 9 and 7 women contestants (BJP, INC and BSP) for the 25 LS seats from Rajasthan in the 2009, 2004 and 1999 elections respectively.

An overall analysis of women’s representation in the 10 Lok Sabha elections between 1977 and 2009 indicates that the high literacy states/Union Territories like Kerala, Lakshadweep, Mizoram and Goa were worse compared to lower literacy states like Bihar, Rajastan and Andhra Pradesh. (table below)

State wise literacy rate and percentage average of women MPs

| State | Literacy (overall) | Male (literacy) | Female (literacy) | Percentage avg of women representatives from different states (1977-2009** |

| Kerala | 94 | 96.11 | 100.76 | 4.00 |

| Lakshadweep | 91.85 | 95.56 | 82.69 | 0.00 |

| Mizoram | 91.33 | 93.35 | 86.72 | 0.00 |

| Goa | 88.7 | 92.65 | 82.16 | 3.33 |

| Tripura | 87.22 | 91.53 | 78.98 | 5.00 |

| Daman and Diu | 87.1 | 91.54 | 46.37 | 0.00 |

| Andaman and Nicobar Islands | 86.63 | 90.27 | 71.08 | 0.00 |

| Delhi | 86.21 | 90.94 | 68.85 | 10.00 |

| Chandigarh | 86.05 | 89.99 | 64.81 | 0.00 |

| Puducherry | 85.85 | 91.26 | 84.05 | 0.00 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 82.8 | 89.53 | 73.51 | 5.00 |

| Maharashtra | 82.34 | 88.38 | 69.87 | 6.25 |

| Sikkim | 81.42 | 86.55 | 66.39 | 10.00 |

| Tamil Nadu | 80.09 | 86.77 | 73.14 | 4.10 |

| Nagaland | 79.55 | 82.75 | 70.01 | 10.00 |

| Manipur | 79.21 | 86.06 | 71.73 | 5.00 |

| Uttarakhand | 78.82 | 87.4 | 67.06 | 10.00 |

| Gujarat | 78.03 | 85.75 | 63.31 | 7.31 |

| West Bengal | 76.26 | 81.69 | 66.57 | 9.52 |

| Dadra and Nagar Haveli | 76.24 | 85.17 | 47.67 | 0.00 |

| Punjab | 75.84 | 80.44 | 62.52 | 13.85 |

| Haryana | 75.55 | 84.06 | 56.91 | 9.00 |

| Karnataka | 75.36 | 82.47 | 66.01 | 5.00 |

| Meghalaya | 74.43 | 75.95 | 71.88 | 5.00 |

| Orissa | 72.87 | 81.59 | 62.46 | 4.76 |

| Assam | 72.19 | 77.85 | 63 | 5.71 |

| Chhattisgarh | 70.28 | 80.27 | 59.58 | 18.18 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 69.32 | 78.73 | 54.49 | 9.01 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 67.68 | 77.28 | 51.36 | 8.97 |

| Jammu and Kashmir | 67.16 | 76.75 | 49.12 | 6.67 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 67.02 | 74.88 | 58.68 | 7.14 |

| Jharkhand | 66.41 | 76.84 | 52.04 | 3.57 |

| Rajasthan | 66.11 | 79.19 | 47.76 | 9.20 |

| Arunachal Pradesh | 65.38 | 72.55 | 53.52 | 0.00 |

| Bihar | 61.8 | 71.2 | 46.4 | 7.74 |

*Literacy rate source- census2011.co.in

**The percentage average of women representatives from the states was

calculated using the women representatives in proportion to

their total seats during all 10 Lok Sabha elections.

The above data also reveals that smaller states/Union Territories like Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Chandigarh, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Lakshadweep and Pondicherry have never had a woman MP in the last 10 Lok Sabhas.

Women as leaders

More often, it is the attitude towards women brought on by social conditioning, rather than literacy, that determines their visibility in politics. “Kerala society treats women as subservient and is hesitant to accept women leaders. When (political) parties don't dare to field women candidates, how can you expect the public to back them? I would vote for a woman if she is really good and has proven her capability,” says P R Prasad, ex-military man and a voter from the Wayanad constituency.

|

However, voters do not really differentiate between male and women leaders when it comes to performance on key issues that matter to the electorate. In a recent survey conducted by Bangalore-based organization Daksh and the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), which rates the overall performance of MPs across the country on the basis of voter perceptions, women MPs have been rated almost on par with their male counterparts, indicating that if given a chance, women MPs can be equal performers. On the various issues, women MPs got an average score of 5.67 on a scale of 0-10, while their male counterparts were rated 5.75 on average.

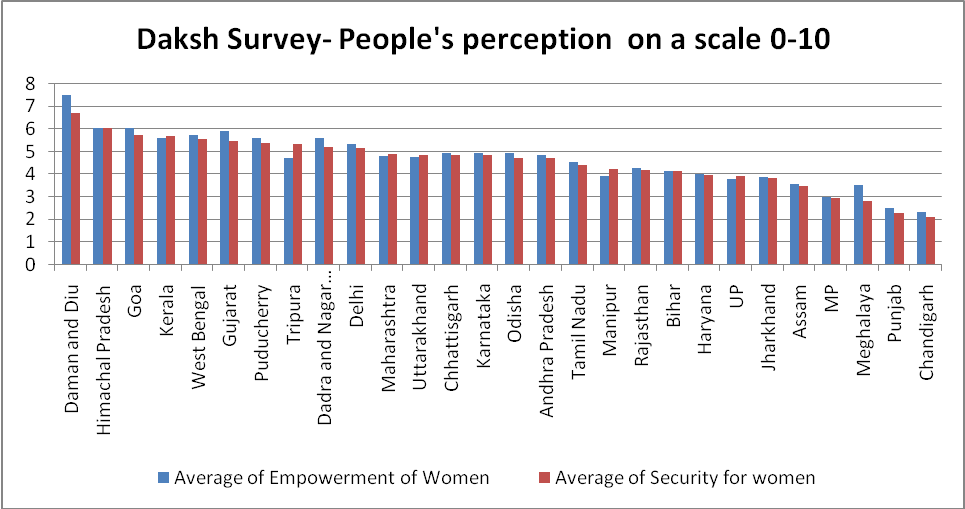

Interestingly, the constituency-wise field survey also shows that while empowerment of women is one of the prime concerns among voters, the states sending the maximum number of women MPs are not necessarily rated highly on women empowerment and security issues. For instance, on these two parameters, the average score of MPs from Uttar Pradesh, which sent the highest number of women to the Lok Sabha in 2009, is among the least.

Note: The final scores of constituency-wise ratings for all MPs on the issues of women empowerment and security of women are aggregated state-wise, and then averaged.

Women's reservation bill

So, is reservation the only way to bring in more women in the Parliament and get them to engage in the political process? Most of the major political parties seem to think so - the BJP, Congress, the Aam Aadmi Party and CPI (M) have all promised to push for the Women's Reservation Bill (ensuring 33 per cent reservation for women in parliament and state legislative assemblies) to be passed, if voted to power.

The Constitution of India empowers the Government to make special provisions to safeguard the interests of women as detailed in Article 15 (3) and Article 39. The 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendment Act mandated that one-third seats in the elected bodies in India at the village, block, district, and municipal level be reserved for women. However, no specific provisions exist for reservation for women in political offices and jobs.

Among the two major national political parties, the BJP and Congress, between 1984 and 2009, the INC has fielded more women candidates compared to the former, except in 2009 when the BJP fielded one additional woman candidate.

“Unfortunately, for political parties, the winnability of the candidate matters the most; accordingly, their family background, financial position, political influence and personality traits are considered while giving a ticket. So, not many women qualify to contest. Hence, women’s reservation is the only way to bridge this gap,” says Dr. Tamilisai Soundararajan, National Secretary of the BJP.

Notes on methodology

1. Data for all the national elections were downloaded from the Election Commission website.

2. Google Spreadsheets and Google visualization charts were used to generate motion charts for the data downloaded above.