Anyone in India who has had a brush with a court case would understand the axiom: Justice delayed is justice denied.

There are over 22 lakh cases in India at present that have been dragging on for over ten years. There are nearly 4,400 vacancies of judges in subordinate courts in the country as on December 31, 2015, while the 24 high courts face a shortage of over 400 judges.

Sources who have been tracking court cases say that if the current rate of disposal continues, it will take over 300 years to dispose of over 2.19 crore cases. Many petitioners will never hear the judgment as it would invariably come after they have died.

Pending Cases

According to the National Judicial Data Grid, there are more than 2.19 crore cases pending. Out of these, 22.3 lakh cases have been pending for more than 10 years, 37 lakh cases for 5 to 10 years and 64.3 lakh cases for 2 to 5 years. It is an issue that should cause alarm for any government.

There are less than 15 judges per million in India. Twenty-nine years ago, the Law Commission had recommended that the strength of the judiciary should be increased as soon as possible to ensure that there were at least 50 judges per million. That has not happened.

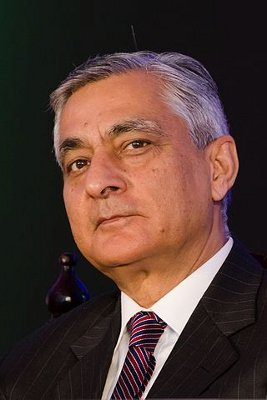

In the last five months, the 43rd Chief Justice of India, Tirath Singh Thakur, has raised the question of pending appointment of judges many times. He has minced no words at every occasion when he has been forced to raise the issue as the executive and the judiciary is not seeing eye to eye on the issue of appointments. He said that the logjam in appointment of judges to HCs was unacceptable and the judiciary could not be brought to a grinding halt.

Last fortnight, the confrontation between the centre and the judiciary was apparent once again when it cleared only 34 names out of the 77 recommended by the collegium for appointment as judges in various high courts. The remaining 43 recommendations were sent back to the Supreme Court for reconsideration.

Piling cases

Meanwhile, a parliamentary panel has decided to seek the views of the Law Ministry on "inordinate delay" in filling up vacancies in the Supreme Court and the 24 high courts of the country. This has happened after the Chief Justice lamented "inaction" by the executive to increase the number of judges from the present 21,000 to 40,000 to handle the "avalanche" of litigations. Way back in 1987, the Law Commission had recommended that the ratio be increased from 10 judges per 10 lakh people to be increased to 50 judges. But it has been ignored.

Chief Justice T. S. Thakur. Pic: Wikimedia Commons

On April 25, Chief Justice Thakur had raised the issue during a meeting of chief justices and chief ministers in the presence of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and urged him to move on this issue. A Lok Sabha discussion in March indicated that 44 percent of judges needed to be appointed in high courts, 25 percent in subordinate courts and 19 percent in the Supreme Court.

Chief Justice Thakur did not mince words when he said that it was easy to criticize the judiciary but what was required was to lessen the load of judges by filling up vacancies as it was stuck up at the government level. “People have started feeling the pinch because of delay in dispensation of justice. The government must tell us what the problem is," he said.

Again, when Modi did not refer to the increasing pendency in his Independence Day speech, the Chief Justice said that he was disappointed. “You may make roads, schools, hospitals, but please also say something about people waiting for justice,” he had said.

Long road to justice

The fact that two-thirds of the prisoners languishing in Indian jails are awaiting a hearing is telling. Many have been waiting for years. By the time their case comes up for a final hearing, they would have already completed what could have been their sentence if convicted. And if they are found innocent, how can the state compensate them for the travesty of justice? Disturbing questions.

Allahabad High Court Building. Pic: Wikimedia Commons

Sadly, 80 percent of the backlog in the appointment of judges is in nine mainline states with large populations. The Allahabad High Court has 88 vacancies, Madras High Court, 40 and Punjab and Haryana High Court, 37. Worse, judges spend an average of about 2.5 minutes to hear a case. In another five minutes, they decide the fate of their clients. That is the kind of pressure they face to dispose what seems an endless mountain of cases. While speed in dispensing cases is paramount to ensure full access to justice, it must be ensured in a manner that does not compromise the quality and fairness with which disputes are resolved.

The Law Commission of India has been underlining the paucity of judges for almost 30 years now, but it has fallen on deaf ears. Eminent jurist Ram Jethmalani said that while India was blessed to have the kind of judiciary it had, the government was not investing in improving the infrastructure and appointing the necessary judges.

Common man hit

A robustly functioning judicial system bestows faith among citizens that their democracy is alive and there is a rule of law. This is the big crisis that the judiciary has to face today. Maybe, that is also what is exercising the chief justice who feels that pendency is now affecting the common man’s search for justice. After all, a well-oiled judicial system that delivers speedy justice is the hallmark of a good democracy. Delayed justice also affects the social, economic and political fabric of the country. As India is at the crossroads of change sweeping the world, it can ill-afford a weakened judiciary.

Ever since the apex court rejected the NJAC Act and restored the collegium system to appoint judges, there has been palpable tension between the government and the judiciary. It is a stroke that political entities are not likely to forget soon. Clearly, the government wanted to exercise its powers in appointments.

A comparative analysis of case pendency shows that Uttar Pradesh is leading with 51.3 lakh cases, followed by Maharashtra with over 30 lakhs, Gujarat, over 22.4 lakhs, Bihar, over 14 lakhs and Rajasthan with over 13 lakhs.

At the end of 2015, there were 426 vacancies in High Courts where the total sanctioned strength is 1,029. In subordinate courts, while the total sanctioned strength is 20,358, only some 15,360 are occupied. Just filling up the vacancies wouldn’t solve the problem. We also need more courtrooms to the 16,513 which are there in India presently. In case these vacancies are filled, 3,989 more courtrooms would be needed.

Reasons and effects of the delay

Daksh, a civil society organization, conducted an empirical study called “The Access to Justice Survey” by interviewing litigants in several district courts from November 2015 to February 2016. The surveyors physically visited 305 locations in 170 districts of 24 states in India. The reasons litigants gave for delay in their cases ranged from judges not passing orders quickly to other parties not appearing in courts. As many as 49.3 percent of the respondents felt that there were not enough judges for civil cases, while 50.4 percent felt there were not enough judges for criminal cases. Over 63 percent felt that there were too many cases in the court and 3.8 percent were waiting for more than 10 years to see their cases disposed off.

Some workable solutions

Pendency of cases is a complex issue that has no easy answers. But some plausible solutions can be put into place:

- Court infrastructure has to be improved to meet the increasing pressure.

- Technology that can cut red tape and delays should be exploited.

- All the vacancies should be filled as soon as possible.

- Court administration should be tightened.

- There must be a system to deal with or change cumbersome procedural laws that delay administration of justice.

Daksh also focused on the economic impact of undue delays in court cases. The survey states that the loss of productivity due to attending repetitive court hearings because of wages and business lost came to 0.48 percent of the GDP. Civil litigants were found to spend Rs 497 per day on average for court hearings. They incurred a loss of Rs 844 per day due to loss of pay. Criminal litigants spend Rs 542 per day for court hearings on average and incurred a cost of Rs 902 per day due to loss of pay. The average cost incurred by the litigants per day per case came to about Rs 1,039. This indicates that only those who can afford such a high cost of litigation can afford resolution of their legal disputes. This goes against the constitutional provision that guarantees equal protection of the law to every citizen.

The Campaign for Judicial Accountability and Judicial Reforms (CJAR) that advocates judicial reforms boasts of highly respectable patrons such as former Justice PB Sawant, Supreme Court of India, Justice H Suresh, former judge, Bombay High Court, Arundhati Roy and Banwari Lal Sharma of the Azadi Bachao Andolan among others.

In a statement, they said: “Closing down the courts for extended periods of time during the long summer months is a vestige of colonial India. There is no justification in a modern democracy to retain the colonial practice of long vacations for courts. Judicial officers should get service benefits, including leave and vacation benefits, similar to what other public service officials of comparable seniority get.”

No time-limits for cases

The 245th Report of the Law Commission of India on Arrears and Backlog said that one of the problems was that India does not have general statutory time-limits for cases as the US does through its Speedy Trial Act. While the Civil Procedure Code and the Criminal Procedure Code have time-frames for completing certain stages of the case, these statutes generally do not prescribe time limits within which the overall case should be completed for each step in the trial.

The Malimath Committee in 2013 recommended a two-year time-frame as the norm by which delay and arrears in the system should be measured. Additionally, the Law Commission report mentions that the Supreme Court has also recently advocated the use of case-specific time tables for the timely disposal of cases.

However, the 245th Report did not recommend mandatory time-frames for disposal of cases as it feared it would affect the quality of judgments. Instead, the Commission recommended using the Rate of Disposal Method to determine how many additional judges should be appointed to clear backlog for an interim period until when the judiciary’s human and physical infrastructure could be increased.

Clearly, India is faced with a serious problem of dispensing justice the way it should. Unless a concerted move is made to address the ills of the system, it will continue to be long road to get justice.