One of the first responses of the Union Government to the COVID-19 pandemic was notifying it as a 'disaster' under the Disaster Management Act (DMA), 2005. This declaration empowers the Ministry of Home Affairs to direct state governments and curtail freedoms in order to tackle health crises. These restrictions, though, severely affected the livelihoods of street vendors, pushing many of them closer to poverty. Women vendors were especially hard-hit - enduring economic hardships, along with gender-based violence and other oppressive social norms.

On 28 March 2020 the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), taking into account the possible impact of COVID-19 restrictions on the poor and vulnerable, instructed states to "adopt a humane approach in dealing with the public, particularly those who are left adrift by the lockdown. Enforcement of the laid down restrictions must be tempered with compassion and a sense of duty of care for our citizens." Despite this, however, the ground reality did not change.

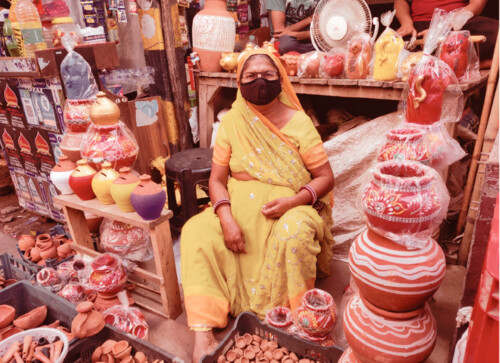

At the Centre for Civil Society, we conducted interviews with 40 women vendors (from Delhi and Rajasthan) to document their experiences during the lockdowns, and consider the likely governance and policy implications. Of the respondents, 82 per cent reported earning no income during lockdowns, and the rest reported earning only a small fraction of their pre-covid daily earnings. Almost a third of the respondents sold essential goods such as fruits and vegetables. Even though various government orders permitted the sale of essential goods, none of the women vendors were able to continue vending during the lockdown.

The barriers to their livelihoods did not lift fully even when the lockdowns were lifted last July. One sixth of the women confirmed that they were restricted by local officials from conducting business post July 2020. This reflects a larger trend documented in other research, which found that over 45 per cent of the street vendors and shopkeepers accused of violating COVID-related orders were providing essential services and goods (CPA Project 2020).

Of those who continued street vending after the first lockdown was lifted, four-fifths reported that they faced restriction in some form or the other. Executive orders restricted the time of operation and number of people allowed at each stall. Most executive orders did not provide a clear justification for allowing vendors to set up stalls only on particular days and during set time periods. Recently, courts have declared similar classifications arbitrary.

Nearly 59 per cent of the interviewees reported that, apart from these orders, additional arbitrary restrictions were imposed by the police or local municipal officials. "They did not even allow us to set up our shop until we pay them", said one street vendor. Nearly 28 per cent reported that their goods were arbitrarily seized under the garb of violating COVID-19 norms, and that they would often have to bribe officials to recover them. A few even mentioned, "my goods were destroyed by local officials"—this was reportedly done out of spite when the vendors could not pay the bribes demanded.

Nearly 59 per cent of the interviewees reported that, apart from these orders, additional arbitrary restrictions were imposed by the police or local municipal officials. "They did not even allow us to set up our shop until we pay them", said one street vendor. Nearly 28 per cent reported that their goods were arbitrarily seized under the garb of violating COVID-19 norms, and that they would often have to bribe officials to recover them. A few even mentioned, "my goods were destroyed by local officials"—this was reportedly done out of spite when the vendors could not pay the bribes demanded.

Other research has documented that in 2020, "over 75 per cent of all street vendors ... were accused primarily on the grounds that they had opened their shop or continued their trade and gathered crowds, increasing the risk of spreading the virus. During the first and second lockdown, over 50 per cent of street vendors' goods, carts or two-wheelers used for trade were confiscated by the police". This, along with the interviews, reveal how restrictive orders and abuse of power have a disproportionate impact on the poor. They add to the financial distress of the informal economy and may exacerbate the socio-economic vulnerabilities faced by women vendors.

Best practices in responding to crises

At the onset of the pandemic, the World Health Organisation, while calling on countries to take "urgent and aggressive action", also noted that "countries must strike a fine balance between protecting health, minimizing economic and social disruption, and respecting human rights". The experience of vendors, migrants and many others at the edge of social and economic vulnerability in the country suggests that this balance was not really sought, let alone achieved.

Unlike countries such as New Zealand, Sweden, and Taiwan, India has not enacted any specific legislation to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, the executive in India created a complex web of orders under the Disaster Management Act, 2005 (DMA), the Epidemic Diseases Act, 1897 (EDA), and the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1974. All actions undertaken by the government to control the outbreak are based on these three legislations. But none of these provides any safeguards to prevent arbitrary conduct or misuse of powers on part of the executive. The DMA and EDA both fare poorly on all four principles that play a key role in promoting the rule of law and protecting individual rights.

Guidance on discretion: An executive action involving discretion must be guided by certain criteria. Without this, it may be difficult to assess whether a particular administrative decision is based on proper considerations. Neither the EDA nor the DMA provide any guidance on how discretion must be exercised by the executive. For instance, Section 2 of the EDA allows a state government to "take...such measures and... such temporary regulations to be observed...as it shall deem necessary to prevent the outbreak of such disease.” This mandate is not accompanied with any guidance on either the form of orders that can be issued or their subject matter.

Procedural safeguards: Any government action which deprives an individual of their life, liberty, or property, must follow due process. At the minimum, this includes getting an advance notice of such a government action; an order detailing the reasons for undertaking the particular action; a reasonable opportunity to be heard before such a deprivation is enforced; and a mechanism to challenge the executive's decision. The DMA and the EDA, however, do not provide these safeguards.

Principles of proportionality and nexus: Principles of proportionality help ensure that when the government acts, the means it chooses should be well adapted to achieve the ends it is pursuing. However, some of the orders issued under the EDA and the DMA, to control the spread of the virus, were disproportionate. For instance, the Odisha Government banned the use of all private vehicles as a curfew measure. This was eventually questioned by the High Court on grounds of proportionality.

Control over delegated legislation: Since rules and orders are not made by elected representatives, or subject to close scrutiny, the legislature must ensure that these do not run counter to the interests of the people. The parent legislation must lay down guidelines on the subject matter that rules and orders can regulate. The DMA and the EDA do not provide any such guidance to the executive. Consequently, the orders issued under these laws provide sweeping powers to district officials, who are further empowered to issue more orders.

States responded in different ways to tackle the crisis. While some states issued regulations and orders under the EDA, others - Rajasthan and Karnataka - introduced their own epidemic disease laws. These state level laws grant expansive powers to the executive, and fail to institute safeguards to protect the rights of individuals against abuse of power. Finally, even though the EDA requires the regulations enacted under it to be 'temporary', these regulations do not have an end date.

Recommendations

India is yet to incorporate three key principles that must be part of a country's legal framework while responding to a public health crisis - legal certainty and clarity, which covers the conditions under which laws can be brought into force, and specific methods, procedures, timelines, etc. for orders to be issued, enforced and ended; respect for international human rights norms, to ensure that when rights are restricted to tackle health crises the restrictions are proportionate; and oversight of actions pertaining to delegated legislation. Learning from, and incorporating such mechanisms, would make the Indian Parliament's role robust in preventing executive overreach.

How can we apply these learnings to our country? The expansive language of the DMA and the EDAs has allowed the executive to act arbitrarily. However, there are multiple ways in which the legislature can check the powers of the executive to uphold the rule of law. Below, we present some recommendations based on international best practices outlined.

1. Guidance for executive orders: The EDA and the DMA must both be amended to provide for a list of the subject matters that the executive may regulate and the nature of restrictions that can be put in place. The Acts must also mandate executive orders to mention the date of force, area of applicability, and the section and sub section of the Act under which powers are exercised. These will not only help ensure legal clarity in the laws, but also the orders issued under them.

2. EDA and DMA must mandate executive orders passed during emergency to be temporary and undergo Parliamentary review. India's legislative framework grants powers to the Centre and the states to prescribe regulations, but these are not required to be laid before the respective legislatures. The EDA and the DMA must be amended to mandate review of the rules, specify a time-limit for such laying and passage, and most importantly, empower the legislature to revoke any rules which it deems unnecessary to counter health crises.

3. Parliamentary or Standing Committee review must be guided by certain principles. These include: checking whether the orders go beyond the mandate of the Parent Act; checking against arbitrary or excessive restrictions on freedoms; checking against lack of clarity or limited guidance that gives the executive scope for abuse of power; ensuring the order allows for review of decisions that affect life, liberty, rights, obligations, and interests; checking whether the order contains matters more appropriate for enactment by the Parliament; and checking whether the order is freely accessible.

India currently has sub-committees under both houses of the Parliament to review subordinate legislation. These sub-committees are empowered to test whether an executive order is in line with the provisions of the Constitution or the Act pursuant to which it is made, and whether it contains matter which in the opinion of the Committee should more properly be dealt within an Act of Parliament. These committees, however, have not made any observations on the COVID-19 specific executive orders. The mandate of these committees also does not include reviewing subordinate legislation on some of the principles listed above.

4. EDA and DMA must provide a mechanism for appeal against the decisions of the executive. Currently, no mechanism to appeal decisions exists in the DMA and the EDA. This prevents any person impacted by orders of the executive authority to seek administrative recourse, leaving only the already overburdened High Courts or the Supreme Court as an option to challenge the restrictions imposed.

India had previously proposed the Public Health (Prevention, Control and Management of Epidemics, Bio-terrorism and Disasters) Bill, 2017 to tackle public health crises. It sought to incorporate the aforementioned principles of legal clarity, legislative review, and appeal mechanism. The Bill defined key terms like 'isolation' and 'social distancing', which currently remain undefined in law. The Bill also articulated a mechanism for the Parliamentary approval of executive orders, and attempted to introduce a procedure for appealing against an executive order. The Bill, however, was not enacted.

Nevertheless, every crisis presents one with the opportunity to prepare better for the future. Similarly, this pandemic has shed light on several international legal norms which India can assimilate to strengthen its own structures. Hopefully, the norms we institute would protect India’s impoverished and disadvantaged through any crises in the future.