Towards the end of September, several districts in West Bengal such as Bankura, Birbhum and Burdwan have seen citizens rise angrily against ration dealers leading to violence and arson, creating a collapse in the law and order situation in many parts of these districts. It gradually spread to Midnapore (West) and Murshidabad, a very poor district in the state.

The agitators have squarely accused the ration dealers of manipulating the supplies of wheat and rice for the open market by selling them at a higher price. In other words, the dealers, appointed by the government to run the system, have actually sabotaged it. The Public Distribution System - the principal social security measure for a Marxist regime - has almost collapsed in these areas of the state. Ironically, there is no food shortage in the ration shops for failed crops or drought or flood. There is no report of irregular supplies from the food department. The fault - or should we call it crime - lies at the door of the ration dealers, many of whom are CPM (Communisty Party of India - Marxist) functionaries presiding over the Panchayati Raj.

•

Undermining Kerala\'s fine PDS

•

Bureaucracy stands in the way

Around the same time, nearly 500 armed residents of Gug village, 15 kms from Dakhalbati, arrived at Raghunath Mandal's house-cum-shop and he fled with his family. When the police arrived, they were attacked with rods, swords and brickbats, leading to five of them being badly injured including inspector-in-charge Sujit Ghosh. Last week, residents of five villages in Harishchandrapur's Milangad Kobaiya area slapped a fine of Rs.3 lakh on ration dealer Setabuddin following a collective meeting. When the dealer refused, they decided to socially boycott him. Their complaint is that Setabuddin has been distributing rations just twice a week over the past 12 years and that too, at a much-reduced quantity. Setabuddin has not denied the charge but has not agreed to pay up.

These attacks that began with the anger of the common man against the ration dealer, soon took on a political colour as Trinamool Congress, the main opposition of the ruling party pounced to make political capital of the situation. The same day, Mamata Banerjee visited Sonamukhi in Bankura district where seeds of the ration rage were sown on September 16. She announced a string of statewide programmes against 'corruption' in the food distribution system. More than a fortnight later, we are yet to know what these 'string of statewide programmes against corruption' are.

In Mahulara, Trinamool Congress leader Chittaranjan Rakshit led villagers to ration dealer Jamaluddin Sheikh's house. They clashed with alleged CPM workers, hurling bombs at each other. The police then resorted to a baton charge to bring the situation within control.

Panchayat elections and the ration issue

Since 1978, when the Panchayat elections began in the state, the CPM has been winning hands down. Interestingly, the reason for its thumping success in rural West Bengal was rooted in its pro-agrarian polices to benefit the farmer. Also, the supply of essential commodities through the PDS has been the cornerstone of Left politics in West Bengal.

But all has not been going well for the party recently, and it has seen losses at the last panchayat elections. In Sitalgram, within Birbhum district, the CPM got a bad beating, not being able to garner enough votes for the 16-member body, ousted by the combined opposition of Congress, Forward Bloc and BJP. The killings in Nandigram and Singur that began in March this year and continues till this day, and the ration riots may be indications that the CPM's power at the local level is on the wane. This is one perspective.

Another perspective doing the rounds is that the ration riots in six West Bengal districts is partly a politically orchestrated riot engineered by the Opposition - the Trinamool Congress with a view to gain a foothold in the forthcoming panchayat elections in the state, which are reportedly slated between January and May next year. Though Raipur in Bankura district is a traditional constituency of the ruling party, Trinamool has reasonable support and the Maoists have gained a stronghold in some pockets. Shyamsundar Sinha Mahapatra, Raipur Zonal Committee Secretary of the CPM, says that the ruling party's strength in numbers in the region is undercut by the fact that 46 per cent of the electorate votes against the CPM. Incidentally, Nirmal Pal, a ration dealer of Motgoda village in Raipur Police Station, hanged himself, leaving a suicide note behid for his wife and children.

Gangajalhati, a village in Bankura district, which is a CPM stronghold, saw public violence against ration dealers in the first week of October. Its neighbouring village, Baro Kumira, faced similar wrath on 4 October when, according to the villagers, the rioting mobs who attacked the house of ration-dealer Biman Kundu, were led by panchayat member Shankar Layek of Trinamool Congress. Unable to meet the mass demand to pay monetary compensation to each cardholder for 11 months of rations within the next two days, Kundu was forced to end his life. Kundu's elder brother Bidhan insists that they have always been strong supporters of the CPM. One brother even won a pradhan's election on a party ticket. But when the crunch came, not a single comrade came to their rescue.

Deeper probing reveals that there is an unholy nexus between the ration dealers and the blackmarketeers, with the overt and covert support of a section of government officials. The system, designed specifically to help the poor, keeps depriving them of their quota of essential food items and fuel. This artificial scarcity has driven many towards starvation and even death. These nefarious profit-making schemes of ration-dealers who sell the supply in the black market, makes their dealings a criminal offence. The government can hardly expect to be exempted from taking responsibility of not being able to provide its citizens with the basic needs of survival. Many of these ration dealers are members of the ruling party.

In fact, Amiya Patra, CPM secretary of Bankura district, said that 24 of the 1245 dealers in the district are party members. What he did not say however is that most of the rest were supporters and donors to party funds. One ration dealer of Sonamukhi in Bankura, accused of hoarding foodgrains, has admitted that he has been funding party programmes. "It would have been impossible to run my business without the help of the party," he said. Hundreds of ration dealers in Birbhum and Burdwan owe allegiance to the CPM, though only a few are its members. Dilip Ganguly, district party secretary, Birbhum, said that out of a total of 976 dealers, only around 12 are party members. A party source who refused to be named, said: "Ours is the ruling party with a strong organization down to the grassroots level. So, the leadership was very much aware that ration dealers sell foodgrains meant for public distribution in the black market. It is not possible for ration dealers to carry on the illegal business without backing from sections of the party."

The party report on Bankura commissioned by Biman Bose, Secretary of the Communist Party of India's West Bengal State Committee, reveals that there has indeed been a diversion of stocks to be eventually sold at higher prices. The district panchayats, who have arrogated to themselves the role of controlling the PDS, most of them powered by the ruling party, are directly involved.

A gory picture

There are around 4.89 lakh ration shops in India, arguably the largest distribution of its kind in the world. The supply of foodgrains and fuel at subsidised prices comes from the Centre. Each state has the onus of appointing ration dealers and distributing the supply among them for selling through 'fair-price' shops allotted at the discretion of the state government. The food department of the Government of West Bengal is wholly responsible for distributing these central supplies among the 20,370 ration shops to fulfill the basic needs of 8 crore people in the state. Any violation of this responsibility amounts to criminal negligence under constitutional law. Yet, this violation has been going on with impunity for 30 years of Left-Front rule in the state.

The ration mafia comprised of party honchos at the Panchayat level, food inspector, ration dealers, distributing officers and the local police is not exclusive to West Bengal. Towards a solution to this blatant corruption that is corroding the basic principle of PDS, in 1999, the government at the centre commissioned the Tata Economic Consultancy Services to conduct a survey. The report of the study revealed that all three target groups of PDS, namely, APL (Above Poverty Line), BPL (Below Poverty Line) and AAY (Antyodaya Anna Yojana) were being deprived of their regular quota due to the diversion of essential supplies by ration dealers in the open market where foodgrains fetch a price much higher than that fixed for the ration shops.

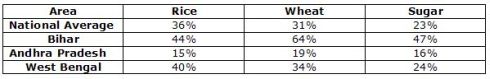

Interestingly, 43 per cent of the rural population who live below the poverty line (according to a Planning Commission Survey) does not figure among these at all as they do not have ration cards! The following abstract from the 1999 TECS Report shows the percentage of diversion which underscores the fact that while diversion of essential supplies is a national problem, there are states like Andhra Pradesh where diversion is very less when compared with the diversion in states like Bihar and West Bengal:

More recently, a 2005 study conducted by the Planning Commission informs that during 2003-2004, of the 14.07 million metric tones of foodgrains released by the PDS for the poor in 16 Indian states, including West Bengal, only 5.93 million metric tonnes of rice and wheat reached poor families (BPL) with ration cards. 36 per cent of the total budgeted subsidy was siphoned off along the supply chain while APL consumers were forced to purchase 21 per cent at black market prices. According to a government survey conducted by the Operations Research Group (ORG-Marg) several years ago, rations valued at Rs.11,336 crores of foodgrains meant to reach the target groups of the PDS, were actually sold in black! The CAG Audit of 2006 proves that West Bengal leads in this.

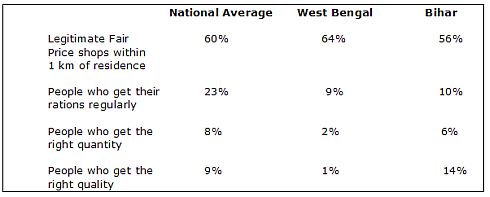

The State of India's Public Service, a report based on a study conducted by the Centre of Public Affairs (April 2002) covering the administration of PDS in 24 Indian states, among other things, lists Tamilnadu at the top while Arunachal Pradesh is at the bottom of the pile. West Bengal ranks a poor 17. How much is being distributed among the target groups in Bengal? The table below is a brief indication.

This table shows that the PDS in West Bengal in terms of available figures ranks poorly not only in comparison with the national average but also with the figures given for Bihar, notorious for the common man's perception of the corruption that forms a part of the system.

The latest in the West Bengal's PDS chaos is that ration dealers across the state are surrendering their licences while many more have pledged to do so in the next few days if the government does not listen to their demand for security. Hasanullah Laskar, state secretary of the dealers' association said that around 6000 of the ration shop owners in the state have surrendered their licences, protesting the government's failure to protect them from villagers' looting and burning of their shops!

The government, on its part, after a high-level meeting of ministers headed by the chief minister, has decided to appoint more than 900 food inspectors to monitor the distribution system. For easy and quick mobility, these food inspectors will be provided with cars, which is absent under the present system.

"Hunger, it is argued, is a problem of distribution: a matter of access to the available global food supply," wrote Robert W Kates in Ending Hunger: Current Status and Future Prospects, in a 1996 issue of CONSEQUENCES. According to Kates, this supports the case for a nutritionally adequate, primarily vegetarian diet, for which production today is sufficient to feed 120 percent of the world's population. Hunger is not a question of fate; hunger is the result of human inaction.

In the case of the PDS in West Bengal, it is the result of gross abuse and misuse of power on the one hand and blatant corruption on the other. Few of these hungry people are conscious that the right to food is a human right protected by international law. Governments have a legal obligation to respect, protect and fulfill the poor man's right to food.