Power outages, low voltage, intermittent electricity supply and load shedding have always been associated with the functioning of the country's electricity supply system. That's odd, considering how much we have invested in power production. India is the world's fifth largest electricity producer.

In 2011-12 the installed capacity stood at 199,877 MW, and it rose to a staggering 267,637 MW by 2014-15. As production increased, the energy shortfall decreased from 8.46 percent in 2011-12 to 3.57 percent in 2014-15.

Unfortunately, these figures are overshadowed by other realities. The Planning Commission's annual report for 2013-14 mentions that in spite of implementing the Electricity Act 2003, the Indian power sector is facing a challenge due to shortages of fuel, a non-remunerative retail tariff regime in many states, and high AT&C (Aggregate Technical and Commercial) losses.

So much so that the Central Electricity Authority's (CEA) Executive Summary of the Power Sector for March 2012-13 calculates the AT&C at 25.38 percent and the T&D losses at 23.4 percent, meaning more than 23 percent of the total power generated was lost during transmission and distribution.

These figures make it imperative to monitor the power sector. The technical slipups and gross mishandling of implementation result in consumers facing poor quality supply in the form of frequent interruptions, load shedding and blackouts, and low voltage levels.

This forces them to invest in alternative power supply sources and voltage stabilizing devices, or suffer inconvenience and loss of productivity. Power cuts also mar the country's economic growth, with businesses and institutions suffering due to unavailability of reliable and good quality electricity supply.

With no checks in place to understand how these disruptions are affecting the development of domestic and industrial consumers, the situation seems gloomy. Creating an efficient monitoring system is key to identifying the loopholes, and eventually generating the solutions needed for better functioning of the entire system.

The Electricity Supply Monitoring Initiative

Prayas, a non-governmental organization based in Pune city has recently delivered something in this regard. The core area of Prayas’ work revolves around health, energy, resources and livelihood, and learning and parenthood sectors of society. The Prayas Energy Group in particular works on the conceptual, theoretical, regulatory and policy issues in the energy and electricity sector. Since 1990, they have been working to bring about sound implementation of energy policies through analysis-based advocacy.

As part of their ongoing efforts to conduct research and generate public participation in power sector regulation, Prayas (Energy Group) has launched a unique programme called the Electricity Supply Monitoring Initiative (ESMI). The beauty of this programme lies in that it simplifies technical data about the electricity supply situation in the country into a language that can be easily comprehended by any concerned citizen, free of cost.

All one needs to do is log on to the ESMI website - www.watchyourpower.org - to have a comprehensive real-time analysis on electricity supply across varied geographical areas.

The journey

ESMI's success story begins with a simple Electricity Supply Monitor (ESM) - a plug-in device that combines a voltage recorder and a communication modem. It can be easily installed at any remote location without the services of an electrician. The devices are designed to operate within the supply range of 130-300 Volts.

The ESM records voltage by the minute at its location and sends the data to a central server using GPRS. Subsequently, all this collected data is analyzed and schematically presented on the ESMI website.

The process of installing ESMs began in January 2014 with the finalizing of specifications, design, and other detailing. The actual field deployment was done only around the month of October with approximately 50 devices installed by the end of the year.

At present, ESMI has been launched in 61 locations across 10 states in India, including 5 mega cities and 16 districts with a few hundred more locations planned to be covered in the coming year.

Shantanu Dixit, Group Coordinator, Prayas Energy Group, shared the thought behind zeroing down on the locations: "Our idea is to work at three levels - the state capital, district headquarters, and the gram panchayat. We have covered four to five districts in each state.” Dixit also informs us that a couple of devices have deployed in the state capital, around 5 devices in each district headquarter, and another few in gram panchayats – adding up to roughly 15 to 20 devices in one district.

“Consequently, we are able to monitor not just the state capitals but also the major cities and towns and villages. On-field deployment primarily depends on the support received at each site and hence, the overall project success would not have been possible without active people participation," he adds.

To promote fairness in data collection, each location has been selected on a random basis. So the study will be not be focusing only on the areas suffering from poor electricity supply. The team intends to study each location for two to three years for a concrete overall assessment of the situation.

The findings and utilisation

ESMI was selected as a finalist for the Google Impact Challenge, India, 2013 which recognises NGOs using technology for social impact.

The ESMI website provides a simple, easy-to-use interface to view information as well as proactively participate in the project. For Prayas, compilation of data has now begun and they have started building evidence of ground realities regarding power supply in the regions where ESMI has been established.

While it is still early days for the project, to bring about a positive change in the statistics, the benefits of such data accessibility are manifold. Apart from ensuring that quality of public service utilities adhere to certain performance standards, it will encourage distribution companies to provide 24*7 uninterrupted supply.

Several of the findings so far have been revealing. For example, a series of monitors in the Udupi district of Karnataka consistently show inadequate power supply from 5 pm to 11 pm. Similarly, a set of monitors installed in Pune district too show a marked difference in power quality supplied in urban and semi-urban areas vis-à-vis rural areas.

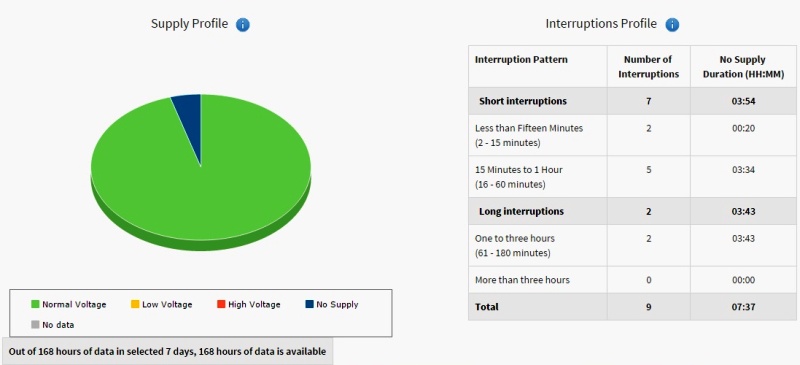

The website provides even more minute and localised data. For instance, between 12 and 18 April 2015, the Jayanagar area in Bengaluru witnessed nine interruptions and there was no power supply for a total duration of 7 hours and 37 minutes.

Sample data recorded in Jayanagar, Bangalore during a week in April 2015. Pic: watchyourpower.org

Again, for Mohol gram panchayat in Solapur district of Maharashtra, for the period of 21 April to 27 April 2015, the voltage report shows that of the total duration of power supply recorded during the period, 74.67 percent saw normal voltage, 21.75 percent low voltage, and 3.58 percent no supply of electricity.

Such evidence-based feedback on the quality of supply can be used to increase the accountability of power supply distributors and improve the quality of supply and fairness in distribution of electricity in the country. Once the hours of power supply availability, interruptions, and data on voltage supply quality are downloaded for further study and comparatively analysed, it can help the industrial sector to better assess the quality of power in different regions, which is a critical input for their operations.

It is also observed that in rural and semi-urban areas, power supply quality for agricultural connections is noticeably poor across all the states. Improving the supply quality would greatly reduce damages to appliances and equipment, especially agricultural pumps and transformers.

Prayas primarily intends to make the data available on www.watchyourpower.org for further research and to initiate debate on power quality among the consumers.

Electricity supply quality information can also act as a base for conducting analytical research, such as a study of the inter-linkages between the quality of electricity supply in a particular area and the health services therein. It could thus provide some answers to developmental shortfalls arising out of poor electricity suppy.

Thus, the evidence-based conclusions arrived at through ESMI could prove to be a vital tool not just in the research on electricity supply but also consequently on health, education and social development.

As Dixit concludes, "Improvement in the situation depends on on-field support and how people respond to the data generated - how the data is shared further with the distribution companies and the power sector actors. Baseline supply quality will improve when the data is used as a tool to verify the performance prescribed by regulatory commissions and people demand for quality supply."

REFERENCES

- Planning Commission, Annual Report on the Working of State Power Utilities and Electricity Departments (2013-14)

- Central Electricity Authority, Executive Summary of Power Sector March 2015